While a five-member Game and Fish Board of Control created in 1909 was viewed as a necessity for game law enforcement in North Dakota, officials knew it wasn't the fix needed to conserve the state's wildlife resources.

The board, it was argued at the time, maintained no permanent office, member turnover was high, no provisions were made for the preservation of files, and "the salary allowed the secretary was not such as to justify a competent man devoting his entire attention to the duties of the office."

Recognizing this, state legislators in 1929 passed a law for a game and fish commissioner to take over the duties of the board, and move the operation to Bismarck.

Burnie W. Maurek

Burnie W. Maurek

Voters approved the measure in June 1930, marking the beginning of the Game and Fish Department as we know it today.

"Burnie W. Maurek of Sanish today was appointed by Governor George F. Schafer as head of the ‘one-man game and fish commission …' Maurek promptly designated Lewis Knudson of Kenmare as deputy game and fish commissioner.

Other appointments to be made by Maurek include a chief game warden, deputy game warden, clerks and office staff," according to the Minot Daily News, July 26, 1930.

It's been threequarters of a century since Maurek's appointment, marking 2005 as the 75th anniversary of the Game and Fish Department.

The one-man game and fish commission originally met some resistance by the state's constituents, but the governor during his campaign strongly urged its adoption.

The game and fish act was rewritten and reenacted by the legislative assembly in 1931, and changes were largely in the direction of clarifying provisions of previous laws, such as those hunting deer during the open season were required to obtain big game licenses for $5.

But there was more to it than that.

Creating a Game and Fish Department had much to do with safeguarding what remained of North Dakota's natural resources that, because of rapid settlement and widespread cultivating of native habitat, contributed to a decline in native birds and other animals.

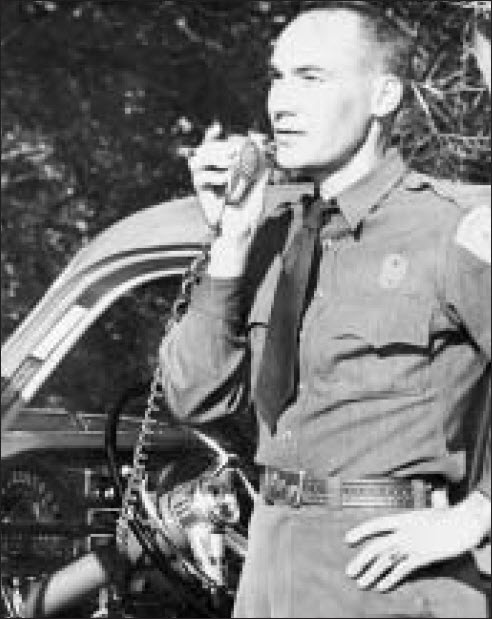

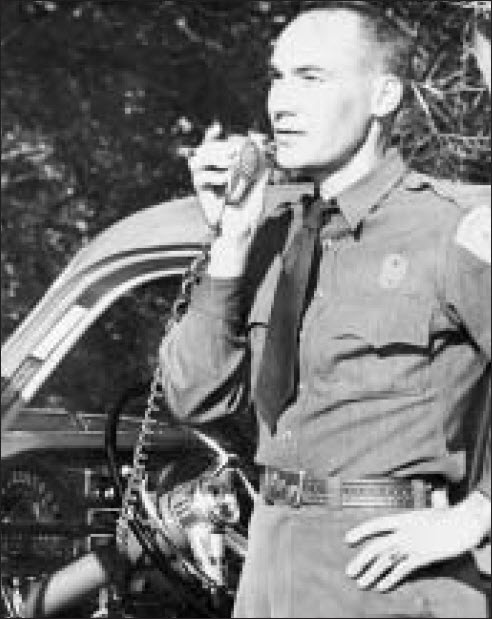

Irvin Riedman, Game and Fish Department chief warden, 1951-55, tries out his new two-way radio, one of the first enforcement mobile units in the state.

Irvin Riedman, Game and Fish Department chief warden, 1951-55, tries out his new two-way radio, one of the first enforcement mobile units in the state.

Individuals with a bent toward conservation understood the need for protection outside the enactment of laws was necessary for the preservation of wild game.

This conservation ethic, interestingly, had taken root, no matter how shallowly, as early as the late 1890s: "Little or no thought was given the future supply of our wildlife.

Who cared? We had plenty of water and an inexhaustible supply of fish and generous bounties of Mother Nature.

Present needs and present gains was the rule of action; which seems to be a sort of transmitted quality which we now, in our more enlightened time, have not fully outgrown.

Even now, a few individuals among us seem willing to destroy the last tree, the last fish, game bird and animal; leaving nothing for posterity," said W.W.

Barrett of Churchs Ferry, superintendent of Irrigation and Forestry, who was designated head of game and fish functions at that time.

By the 1930s, a conservation ethic was more widely received.

People understood the supply of fish and wild game was not bottomless.

It was only about a half-century earlier that bison and pronghorn were prominent in North Dakota.

In 1930, the bison were long gone and pronghorn were just barely hanging on.

"Today the idea of game conservation has the backing and support of a large portion of our citizens and it's recognized as one of the functions of our system of state government, but it should not be forgotten that the pioneers in this movement met with public indifference if not open opposition to the cause which they championed," wrote A.I. Swenson, Game and Fish Department Commissioner, in a report to Governor Walter Welford in 1936.

In Swenson's report, he also wrote that the duties of the Department had continued to grow: "In the early years, the Department's activities were confined chiefly to the propagation of game and fish, and the enforcement of such game and fish laws as were then on our statute books.

In recent years, one of our major activities has been dam construction, for the purpose of conserving water, thus aiding in the restoration of wildlife and other natural resources."

In addition, the Department sought to strengthen its conservation ethic in the early 1930s with a Junior Game Wardens program for young people.

North Dakota Game and Fish Department wardens in full uniform in Dickinson in 1944.

North Dakota Game and Fish Department wardens in full uniform in Dickinson in 1944.

The purpose of the organization, Swenson wrote, was to teach the fundamental principles of conservation as it pertained to wildlife and other natural resources.

The Department also started a monthly bulletin called North Dakota OUTDOORS; sought to improve habitat by planting nearly 70,000 trees; and carried out a battle with carp by removing them from fishable waters.

These efforts came at a time when drought and economic depression of the 1930s added pressure to already diminished wildlife resources on the Great Plains, where a lack of rain turned much prairie farmland into dust.

Dust storms and unemployment, historians say, whipped wildlife habitat destruction and poaching to a peak.

People were hungry, ammunition was inexpensive and game provided high-quality protein.

Waterfowl hit an all-time low, other wildlife populations faltered, and gains made in wildlife restoration since the century's turn began to erode.

This wasn't just the case in North Dakota, but all over the nation.

The nation's wildlife conservation leaders were for good reason concerned, so they acted in the 1930s, fostering what has been described as the most fruitful decade of wildlife conservation.

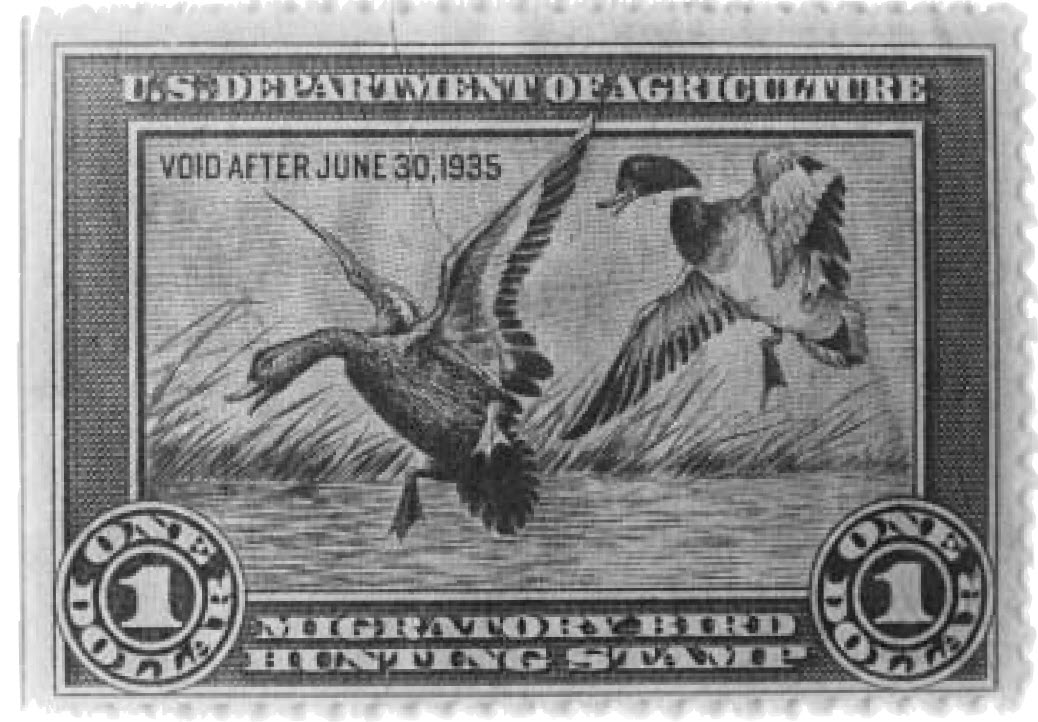

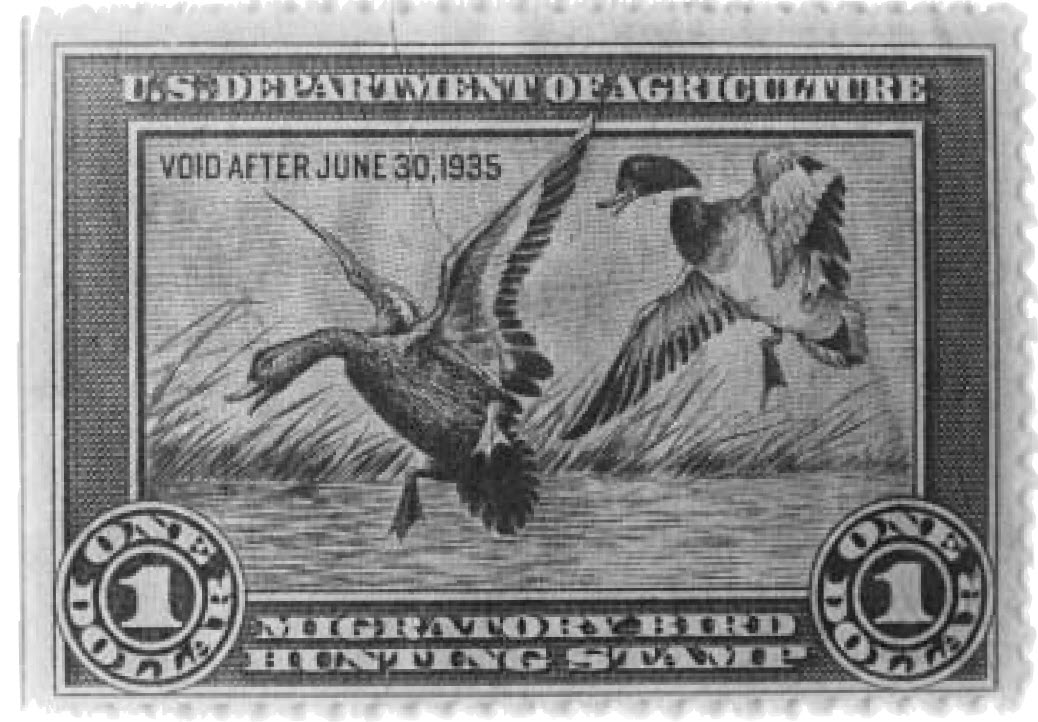

For one, the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act was passed by Congress, requiring every duck hunter 16 years or older to purchase a duck stamp for $1, with the proceeds to be used in the purchase and development of federal refuges.

While this act and others were important, one shines brighter than the rest.

The passage of the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act in 1937 signaled the start of scientific management of wildlife in North Dakota.

The purpose of the act was to make available to states funds to be used for restoring wildlife habitat and aid in the preservation and utilization of wildlife resources.

Funds were garnered from an 11 percent excise tax on firearms and ammunition.

Congress set aside a specific sum collected every year and allocated to states on the basis of size and the number of hunting licenses sold in the state.

Hunters supported this tax on themselves – a rare thing, indeed – for the benefit of wildlife resources.

Prior to P-R funding, Game and Fish Department activities consisted mainly of establishment and enforcement of laws, pheasant and fish stocking and establishment of game reserves.

Funds and experience in wildlife management were in short supply.

License and other fees, plus federal aid dollars from Pittman-Robertson, Dingell-Johnson, and other sources, entirely fund the North Dakota Game and Fish Department. No state general tax dollars are used to fund Game and Fish Department activities. The first North Dakota hunting license was established in 1896 and required for the 1897 hunting season.

License and other fees, plus federal aid dollars from Pittman-Robertson, Dingell-Johnson, and other sources, entirely fund the North Dakota Game and Fish Department. No state general tax dollars are used to fund Game and Fish Department activities. The first North Dakota hunting license was established in 1896 and required for the 1897 hunting season.

The much needed funding enabled Game and Fish to start statewide surveys of game populations, wildlife research, land acquisition and habitat development.

Wildlife population data has since been available to aid in management decisions.

Wildlife research has provided valuable information in predator and game bird relationships, big game and waterfowl populations, chronic wasting disease and other wildlife diseases, and the list goes on.

In 1955, North Dakota had only about 500 free-flying giant Canada geese, nearly all on federal refuges.

A P-R funded program restored Canada goose populations to a point where today these big birds nest in every county in North Dakota.

In 1956, a P-R funded program reintroduced bighorn sheep into the badlands.

Twenty years later, the first of many hunting seasons for California bighorn sheep was held.

Thousands of acres of wetlands, uplands and forest lands have been purchased with PR funds.

Many of the forest land tracts would have been cleared if not purchased.

North Dakota's wildlife management areas, totaling more than 185,000 acres, have been developed and maintained through these programs.

Thousands of North Dakota hunters have taken hunter education courses supported, as well, by P-R funds and volunteer instructors.

The Pittman-Robertson Act worked so well that a similar law for fisheries restoration was passed in 1950.

Game and Fish Department personnel conduct spring northern pike spawning work at Lake Ashtabula in about 1953.

Game and Fish Department personnel conduct spring northern pike spawning work at Lake Ashtabula in about 1953.

The Federal Aid in Fish Restoration Act, or the Dingell-Johnson Act, created a manufacturer's excise tax on fishing equipment, making federal dollars available for fisheries programs.

Under Dingell-Johnson, the federal government contributes $3 for every $1 the states provide for projects such as research, land acquisitions, development of fish habitat and fishing access.

In the 1980s, an amendment to the act expanded the tax to motor boat fuels and imported equipment, making more money available to states.

North Dakota over the years has used the funding to expand hatchery facilities and improve boating access in an effort to keep up with the increasing number of anglers and boat owners.

"North Dakota has benefited greatly from the federal aid programs. Development, land acquisition and research have all helped put game in the bag and fish in the creel of North Dakota sportsmen," wrote Wilbur Boldt, Department Deputy Commissioner, in North Dakota OUTDOORS in 1962.

Boldt wrote those words as the PittmanRobertson Act celebrated its 25th anniversary.

Those words, and ones to follow, ring as true today as they did four decades ago.

"Research is often an unglamorous and frustrating phase of game management. The results often cannot be shown to the impatient sportsman. Results are there, however, and the sportsman has benefited by them … We have learned what is good game habitat and how land can be improved for wildlife. We have learned about wildlife diseases and their effect on man and domestic animals. We have learned the effects of drought and improper land use on game populations. These benefits and many others are the result of Senators and Congressmen who were able to see far beyond how many pheasants could be shot the next fall or how many fish they could catch the next fishing trip. It was their vision that has brought wildlife conservation this far and it will be the vision of men like them who will guarantee hunting and fishing for the common man in years to come," Boldt added.

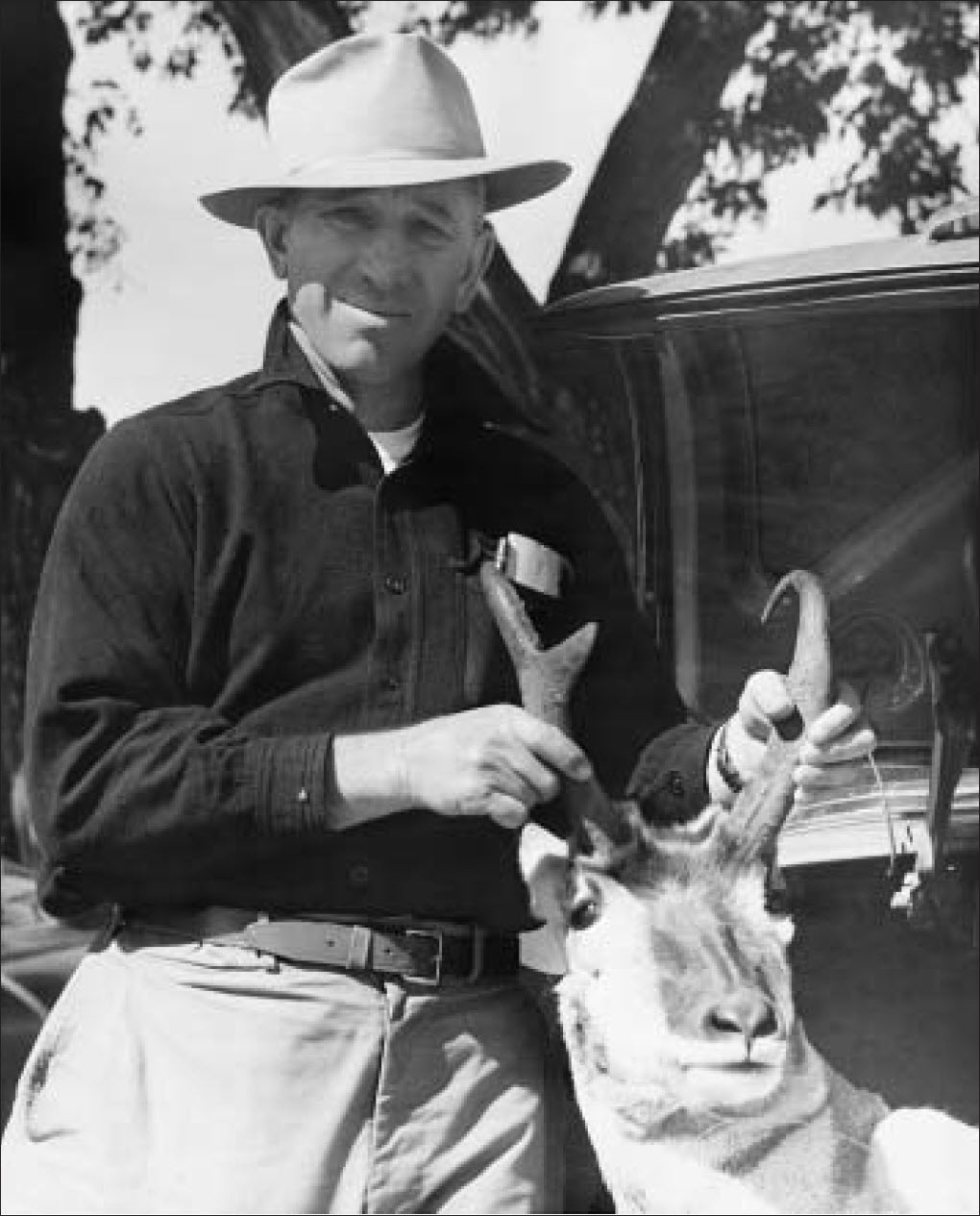

On November 5, 1956, a California bighorn sheep ram was released into the badlands in western North Dakota. The ram was one of 18 sheep trapped in Canada and moved to the state.

On November 5, 1956, a California bighorn sheep ram was released into the badlands in western North Dakota. The ram was one of 18 sheep trapped in Canada and moved to the state.

Bighorns Return to Badlands

In 1956 bighorn sheep returned to the badlands.

Eighteen California bighorn sheep were trapped and transported from British Columbia and released in western North Dakota. Prior to the release, it had been years since the last surefooted animal negotiated the rugged up and down of the badlands.

Restoring bighorn sheep in the badlands was made possible by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration program, or Pittman-Robertson Act.

The first modern-day hunting season for bighorn sheep in North Dakota was held in 1975. Since then, a limited number of licenses have been allotted to hunters lucky enough to draw a license through the Game and Fish Department’s lottery system.

Following a severe bighorn sheep die-off during the late 1990s south of Interstate 94, the Department entered a management partnership with the Minnesota-Wisconsin Chapter of the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep in 1999. In addition to funding a full-time biologist, the group has funded several other management projects the past several years.

Yesteryear

Restrictions on hunting and fish were much more dramatic in the early 1900s than they are now.

Following statehood, hunters and anglers were not used to limits.

They took what they wanted, when they wanted, thinking perhaps the resource was unlimited.

Nowadays, changes in limits and season length due to fluctuating game and fish populations are generally accepted.

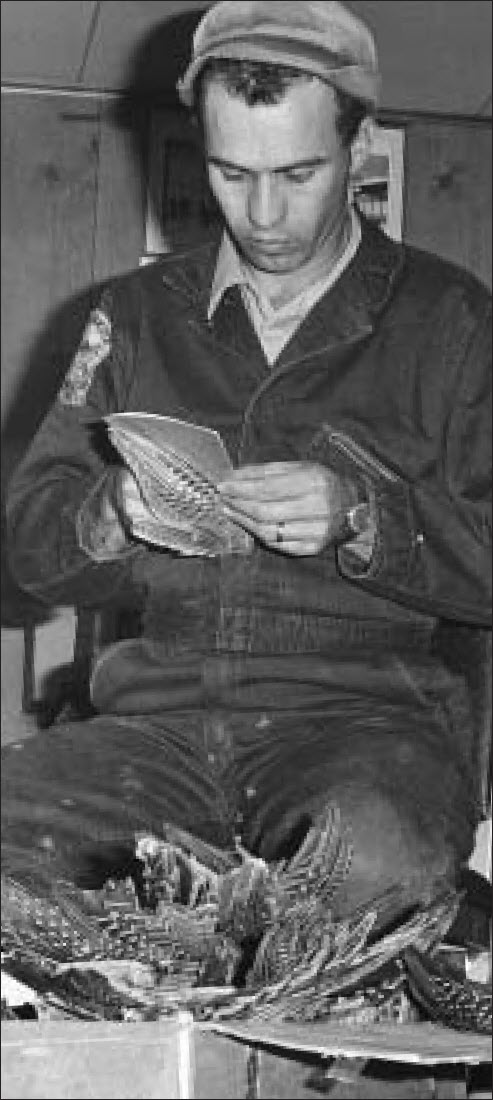

Sharp-tailed grouse and ducks shot in the Bottineau area in 1929 by Glen Powers of Traverse City, Michigan.

Sharp-tailed grouse and ducks shot in the Bottineau area in 1929 by Glen Powers of Traverse City, Michigan.

A look back:

- 1895 – The first daily bag limit of 25 fish was established.

- 1899 – A limit of eight big game animals per year was established.

- 1901 – The deer limit was reduced to five, and the season on bison, elk, moose, sheep and pronghorn closed until further notice.

- 1909 – The deer limit was reduced to two. The upland bird bag limit was reduced from 25 to 10. Fishing restrictions included only one hook or lure was legal for taking fish; no dynamite, poison or lime could be used to take fish; sale of gamefish was illegal; all gamefish had to be 8 inches long before they could be kept; a combination limit of 15 fish daily and 50 in possession was established.

- 1915 – The waterfowl bag limit was reduced from 25 to 15. Deer and ruffed grouse seasons were closed indefinitely.

- 1917 – The upland game bird limit was reduced to five.

- 1919 – The limit on geese was reduced to eight daily.

- 1921 – The deer season opened again, with a limit of one buck per license

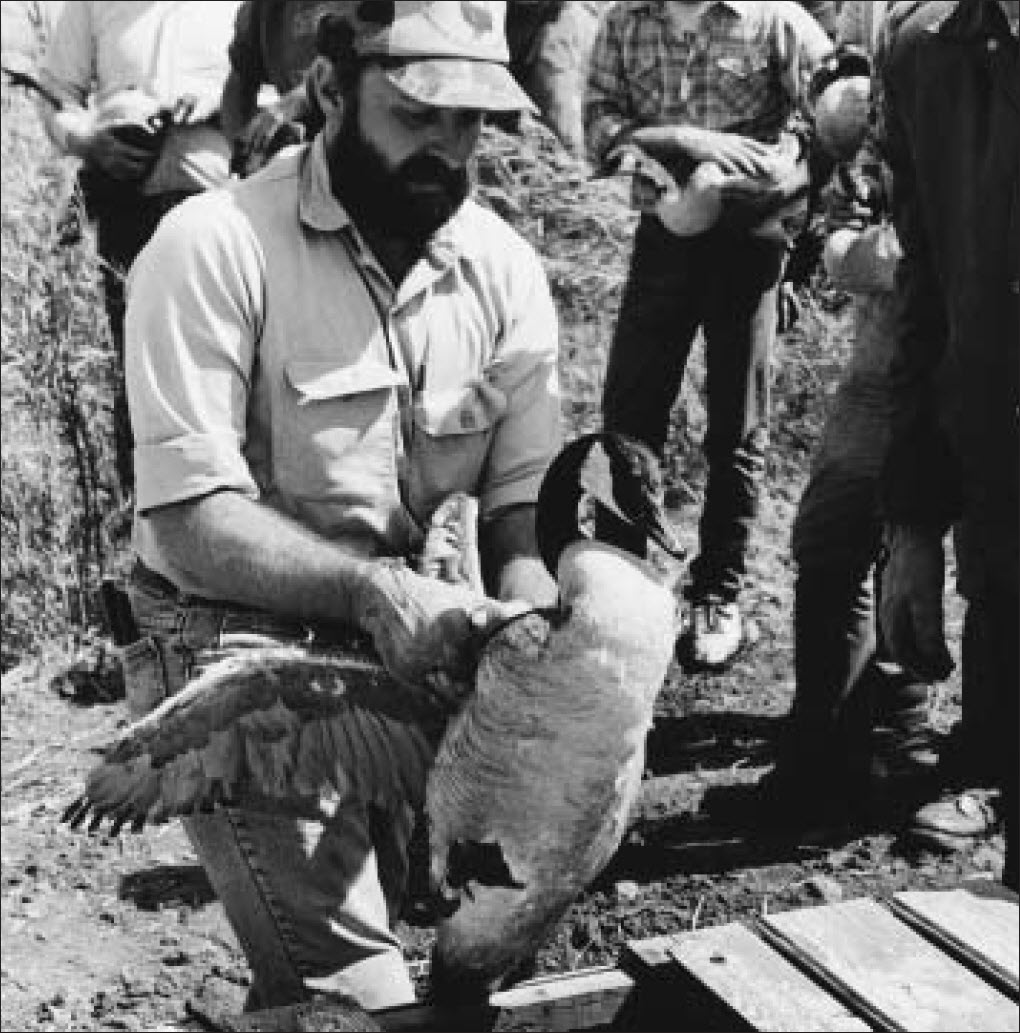

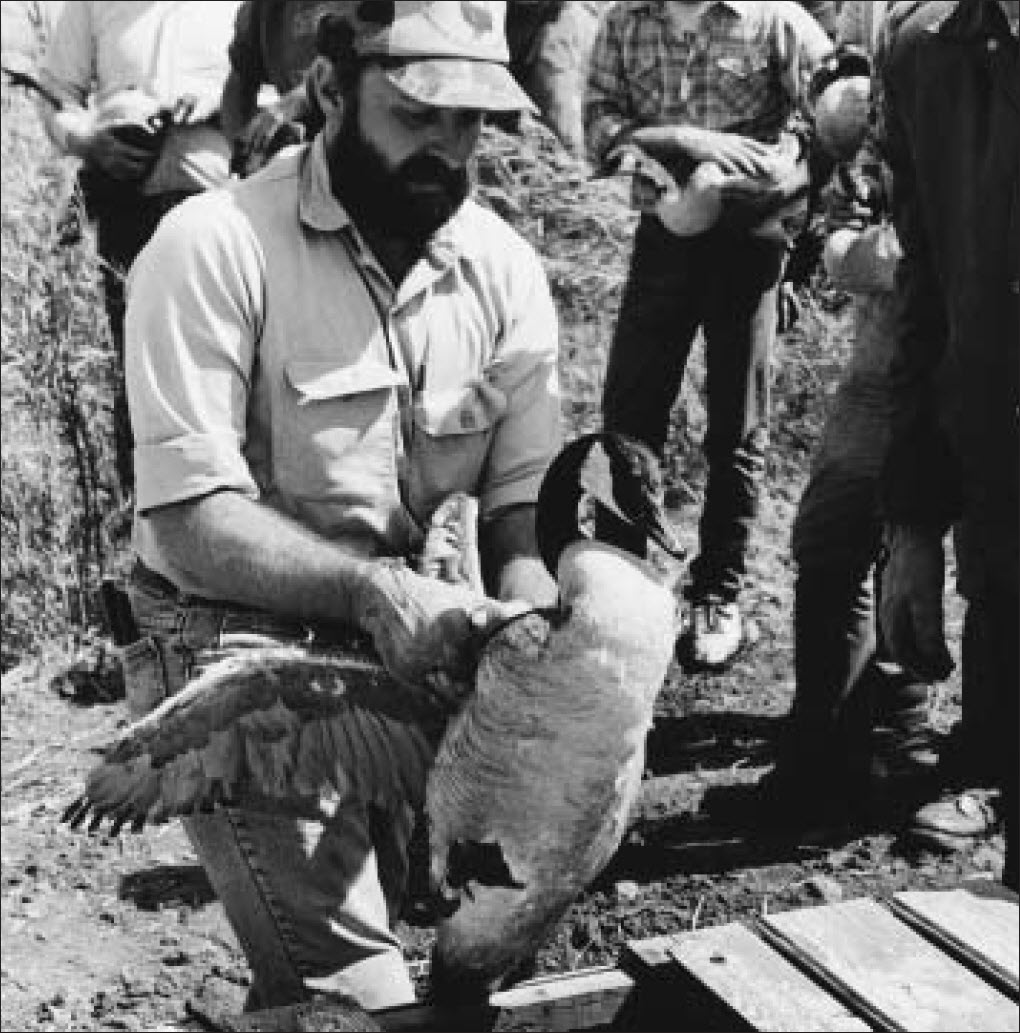

Mike Johnson, Game and Fish Department game management section leader, traps giant Canada geese at Lake Audubon in 1987.

Mike Johnson, Game and Fish Department game management section leader, traps giant Canada geese at Lake Audubon in 1987.

Return of Giant Canada Geese

Since the early 1960s, more than 10,000 giant Canada geese have been trapped, transplanted and released around North Dakota.

Wild breeding pairs of these geese can now be found in every county in the state.

The Game and Fish Department and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have established a goal of 90,000 giant Canada geese in North Dakota as counted during the USFWS spring duck survey.

Starting near zero in the 1960s, Canada geese in North Dakota now number near 180,000 during the spring duck survey, or about double the 90,000-bird objective.

Feathered Foreigners

Ring-necked pheasants and Hungarian partridge, two of the state's popular upland game birds, aren't from around here.

The first Hungarian partridge released in 1924 in North Dakota – about 100 pair – came from Czechoslovakia.

Huns were present in the state prior to the first stocking, most likely migrating to North Dakota from releases in Montana or Alberta.

The first Hun season was held in 1934.

Ring-necked pheasants from China were introduced to North Dakota about the same time as Huns.

They also found the state to their liking, and multiplied to a point where a season could be held.

The first season was 1931, and the pheasant harvest has varied greatly over the years.

Turkey Hunting in North Dakota

Attempts were made in the 1930s and 1940s to stock wild turkeys in North Dakota.

The birds didn't stick, however, and it wasn't until the early 1950s that efforts to introduce this bird turned serious.

The effort was led by the Missouri Slope Chapter of the Izaak Walton League.

Game and Fish Department biologists at the time contended that while they weren't against the group's efforts to introduce turkeys into the state, there was concern about spending sportsmen's dollars in an attempt to introduce yet another game bird species.

By 1958, there were enough turkeys to justify a season.

That year, 376 turkey licenses were issued and hunters bagged 88 birds.

Turkey hunting opportunities have since grown in North Dakota.

The Department's turkey management efforts increased from regulating harvest to an active program of trapping and transplanting wild turkeys from areas where they were abundant to areas that provided suitable habitat.

For the first time in 2003, all of North Dakota was open to fall wild turkey hunting.

Existing hunting units were expanded and much of the central and eastern parts of the state, never open to hunting before, was designated a hunting unit to encourage harvest on isolated, but growing flocks of turkeys.

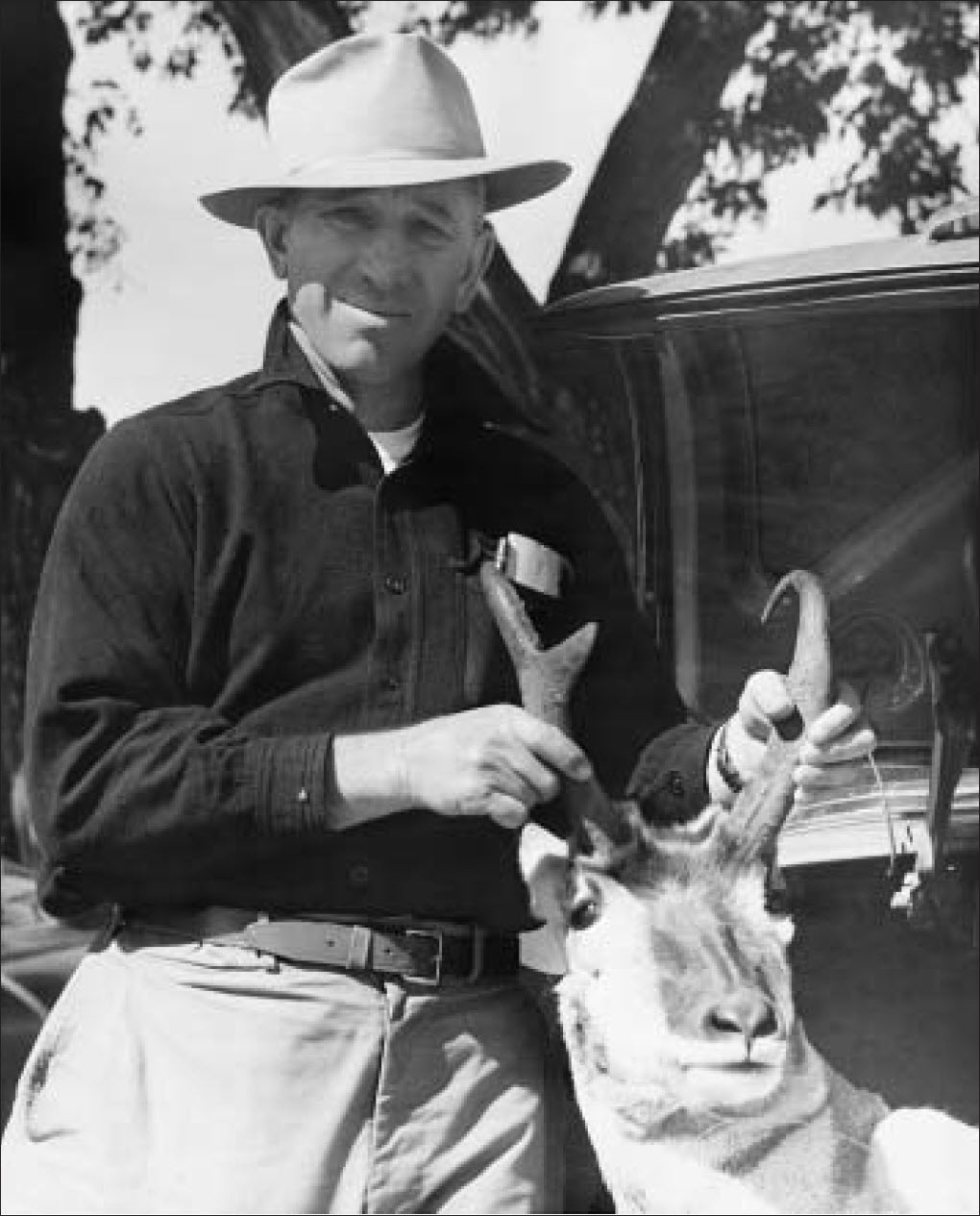

Bob Kernkamp, Valley City, took part in North Dakota’s first modern-day pronghorn hunt in 1951.

Bob Kernkamp, Valley City, took part in North Dakota’s first modern-day pronghorn hunt in 1951.

Looking Back

- The first Pittman-Robertson project was submitted in 1939. A 480-acre land acquisition purchased for $5 an acre, was added to the existing Dawson Refuge in Kidder County.

- The deer harvest for 1941 was estimated at 2,890 animals. Hunters at the time claimed 1941 was one of the best big game seasons ever held.

- It was estimated the state's deer population was 7,000-8,000 animals in 1941.

- The first year hunting was allowed on national grasslands in North Dakota was 1941. Hunters were required to have a free permit before hunting.

- The state's first elk transplant took place in late winter 1942. The animals came from Wyoming and were released in the Killdeer Mountains.

- Following the near disappearance of pronghorn in the state – animals ranged over nearly all the open prairies in the mid1800s, but only about 225 pronghorn remained by 1925 – the first hunting season since 1899 was held in 1951.

- The first statewide bow season for deer was held in 1954. There were 1,119 licenses sold for that first season that ran from October 9-24.

- Any discussion on the state's top fishing waters today would have to include Devils Lake. But in the 1950s, North Dakota's largest natural lake was hardly part of the picture. In the 1940s, the lake was nearly dry.

- Chinook salmon were introduced into Lake Sakakawea in 1976.

- Lake Tschida in Grant County was the "Walleye Capital of North Dakota" in 1961. Twenty-four of 25 fish over 10 pounds reported to the Whopper Club came from Tschida.

- In 1968, creel limits for walleye and sauger were removed on Lake Sakakawea, Lake Oahe and the Missouri River. The next year limits were reinstated, but an angler could still take eight walleye and eight sauger daily.

- With rising water levels, Devils Lake was stocked with fish in 1970-71. By 1972 people were catching fish for the first time in many years.

- The Game and Fish Department held an experimental paddlefish snagging season in 1976 for the first time.

- The state legislature in 1977 passed the hunter safety bill, requiring all hunters born after December 31, 1961 to have taken a hunter safety course before they could purchase a license. The law took effect in 1979.

- The first North Dakota moose season was held in 1977. Twelve permits were issued.

- Department fisheries crews in 1980 made their first attempt to take spawn from chinook salmon during the fall run on Lake Sakakawea.

- Some state school lands in 1983 were opened to public access for the first time. Over the next four years almost all state school land was opened to walking public access.

- The state legislature in 1987 passed a law allowing a tax checkoff to fund a nongame wildlife program in North Dakota.

North Dakota’s native prairie habitat was altered with the arrival of settlers.

North Dakota’s native prairie habitat was altered with the arrival of settlers.

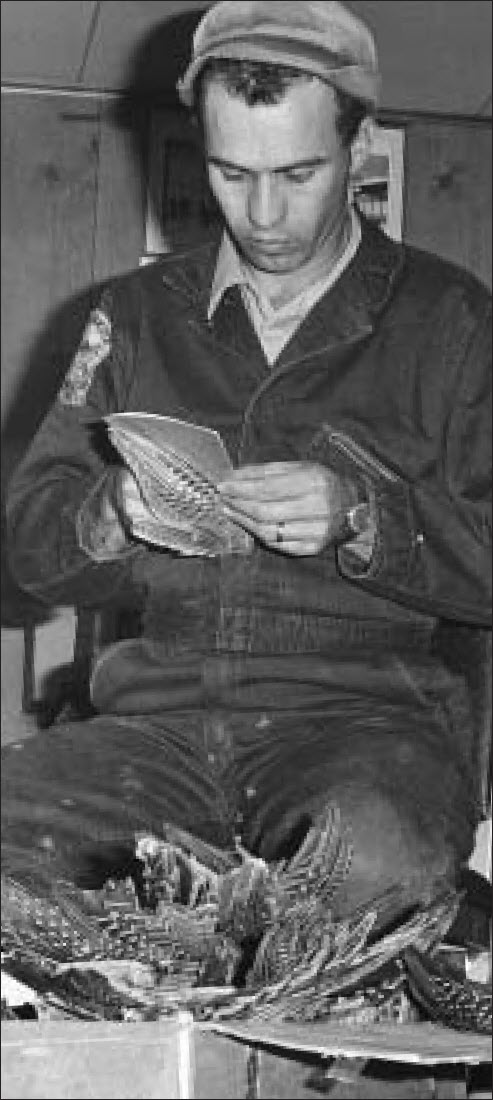

Jerry Kobriger, Game and Fish Department upland game management supervisor, ages sharp-tailed grouse wings in the mid-1960s.

Jerry Kobriger, Game and Fish Department upland game management supervisor, ages sharp-tailed grouse wings in the mid-1960s.

A Wildlife Perspective

When the North Dakota Game and Fish Department was organized 75 years ago, the primary emphasis was on game and fish law enforcement.

The conservation of wildlife through managed harvest was an important first step for the state.

Before that, wildlife was viewed as a resource to be used whenever a person wanted it, with no rules on how, when and where it could be taken, leading to over exploitation and low wildlife populations.

"While game and fish law enforcement still remains a vital function of the Department, the last 75 years have seen a broadening emphasis and more commitment to using science as a basis for management decisions," said Randy Kreil, Department wildlife division chief. "Expansion of biological surveys, management-based research, and technological innovations have changed our understanding of fisheries and wildlife ecology and how to manage these resources."

Another significant change over time is how the Department interacts with the public.

North Dakota has always been a state where the people were able to access and participate in government."Since the Department's creation, it has been recognized that public input is important when making management decisions," Kreil said.

"However, modern communication methods, and realization that public education was equally as important as enforcing laws, has made the Department much better at gathering and assessing public input."

Changes to the Landscape Habitat is the foundation for all fish and wildlife populations.

In the last 75 years, however, there have been considerable changes to North Dakota's landscape.

All of the state's native habitats, which at one time supported vast wildlife resources, have been significantly altered.

While some of these changes occurred prior to the 1930s, the rate of conversion has since accelerated.

"To date, nearly 50 percent of the state's wetlands have been drained, 60 percent of the native prairie has been converted to agricultural land, many miles of stream and river channels have been altered and our rare native woodlands have seen extensive clearing for farming, rural homes and recreational uses," Kreil said.

The result of human development has been detrimental to some wildlife species, while others have benefited.

Typically, as habitats are altered, native species such as sharp-tailed grouse, mule deer, pronghorn and ruffed grouse and waterfowl are affected and their populations and range in the state are reduced.

Conversely, some species are more able to adapt to a landscape altered by agriculture, such as white-tailed deer and the exotic ring-necked pheasant and Hungarian partridge.

Wildlife populations today are generally in excellent to good condition, while there are some species that remain a concern due to a continued loss or degradation of habitat.

In addition, many species that are more adaptable to an agricultural landscape, Kreil said, still depend on undisturbed habitat such as lands enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program.

"There are nearly 3.5 million acres of CRP in North Dakota, which is the primary reason pheasants and whitetails have done so well over the past two decades," he said. "CRP is at a crossroads and North Dakota will see the contracts of nearly half of its acres expire in 2007, with more acres expiring the following years."

If the state experiences a significant loss in CRP, Kreil said, species that depend on this habitat type as part of the agricultural landscape will decline significantly unless something is done to change the trend.

Looking Ahead The most critical concern for the next 75 years is habitat conservation."Without habitat, we'll have precious little wildlife," Kreil said. "With the loss of wildlife, you will rapidly lose the traditions and heritage of hunting, further removing the public from contact with the natural world.

This loss of connection will spiral the loss of habitat even further because fewer people will comprehend its significance."

Assuming the habitat is there in 75 years, another concern is the continuation of a system where the public's wildlife remains available to the public, rather than just to those who can afford to pay for guides and access, said Mike McKenna, Department conservation and communications division chief.

"It is absolutely necessary that political leaders, agricultural organizations, hunters, the business community and the general public clearly understands the value of these resources to North Dakota and in turn make wise decisions to ensure their continued existence," Kreil said.

A Fisheries Perspective

The North Dakota Game and Fish Department's fisheries division wasn't officially designated when the Department was created 75 years ago.

Fish management at that time was nebulous, at best.

In 1949, the first fisheries chief was hired and a small staff put in charge of surveying public waters to determine their ability to hold fish.

In the early 1950s, with the advent of the Dingell-Johnson Act providing federal funding, the ability to collect spawn and distribute fry across the state became the primary management technique, said Terry Steinwand, Department fisheries division chief. "Stocking lakes across the state remained the primary management tool for many years," he said.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, a number of impoundments were created, allowing for more recreational fishing opportunities, thus increasing demand."During that time, regulations became more important, although the biological basis behind the regulations was somewhat questionable since fishing pressure and technology weren't nearly what they are today," Steinwand said.

"From 1970 to about 1990, there was movement forward to a mixture of stocking fish, regulations and, to some extent, aquatic habitat/water quality work." While stocking and regulations are valuable in fish management, they are only part of the mix necessary to sustain a recreational fishery, Steinwand said.

If one component was key to it all, it would be habitat.

"As a result, the fisheries division today is putting more and more emphasis than ever on restoring, enhancing or protecting aquatic habitat," he said. "We've learned much in the last 75 years and depend on what we've learned – and what we are still learning – to best manage our aquatic resources."

In the early 1950s, thanks to a shot of federal funding, the ability to collect spawn and distribute fry to North Dakota waters became an important management technique for the time.

In the early 1950s, thanks to a shot of federal funding, the ability to collect spawn and distribute fry to North Dakota waters became an important management technique for the time.

Changes in the Landscape From a fisheries perspective, the agricultural industry has made enormous strides by recognizing the impact it can have on lakes and rivers if the land is not treated adequately, Steinwand said.

"While this may be true, we are still feeling the affects of many years of land abuse and what it's done to our lakes and reservoirs," he said."Loss of native prairie, wetlands and woodlands appears to be a wildlife issue on the surface, but it also influences the aquatic resource."

When native prairie is lost, it changes the pattern of runoff and the materials in the runoff.

That typically results in excess sediments and nutrients being dumped into waters, ultimately shortening the lives of the fisheries.

Loss of wetlands also reduces the filtration ability of the watershed, while loss of woodlands, primarily along riparian corridors, means no more trees to provide shade, or carbon input via leaves.

"Any loss of these types of habitats will affect fish and wildlife populations," Steinwand said."It's a matter of degree.

One small wetland may have a seemingly minor impact, but the cumulative affect of removing these habitat types can be catastrophic to fish and wildlife."

Looking Ahead

- Habitat – One of the main concerns is the continued loss of habitat. If we continue down the road of the first 75 years, there will likely be only a minimal fishery in North Dakota, Steinwand said.

- Funding and personnel – As the landscape and demographics change, there can be additional pressures to manage a resource. To effectively manage it, adequate time and funding is required to collect the information to make the correct decisions.

- Special interest groups – We've routinely managed the resource for the good and enjoyment of all North Dakotans, Steinwand said. Yet, we've seen other states succumb to special interest groups with an agenda, leading to lost opportunities for other users.

- Lack of water – This is an issue we're dealing with right now concerning the Missouri River System, and will continue to deal with in the future. This issue involves politics on a national level and downstream users with different agendas."We'll have to place adequate time on this in order to even remain status quo," Steinwand said.

This article was written by Ron Wilson and originally published in the March 2005 edition of the North Dakota Outdoors Magazine.