Managing Sakakawea's Salmon Population

There are 1.5 million reasons fisheries biologists will slowly navigate Lake Sakakawea’s shallow waters this month.

That’s roughly the number of chinook salmon eggs North Dakota Game and Fish Department fisheries personnel aim to collect to produce hundreds of thousands of smolts that, months later, will be released back into the big lake.

Last fall, for example, biologists spawned 683 mature females and collected nearly 1.8 million eggs. After sharing some with South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks, fisheries biologists here stocked about 430,000 salmon smolts into Sakakawea in 2017.

This circle-of-life management effort has been going on for years for a nonnative fish species that was introduced decades ago.

Russ Kinzler, Department fisheries biologist in Riverdale, said chinook salmon were first stocked in Sakakawea in 1976, just nine years after the reservoir filled in 1967.

“We started stocking chinook salmon in Sakakawea in 1976 to inhabit the deep coldwater habitat that wasn’t being utilized by other fish, and to give anglers another species of fish to chase,” Kinzler said.

There’s some history to how biologists have collected eggs from Sakakawea’s salmon population. Likely the best known technique from the public’s perspective was a manmade salmon ladder that was introduced in fall 1987.

The ladder was placed in Rodeo Bay at Lake Sakakawea State Park where the salmon, following an ancestral urge, would migrate in fall in search of a stream in which to spawn. Yet, the only running water to be found raced down the ladder.

“Fish entering the large pipe climbed regularly located steps and upon reaching the top were gently washed down the smaller pipe into a holding net … It was an efficient operation, the culmination of many years of hard work,” according to the 1988 April/May issue of North Dakota OUTDOORS, describing the first fall the ladder was put to use.

The last time the ladder was used was 2004.

The installation, takedown and the continued monitoring the ladder required each fall was labor intensive. And the number of migrating chinook salmon ascending the apparatus was too unpredictable and didn’t justify the effort.

Today, biologists collect the majority of the salmon they need by stunning fish in the shallows on the east end of Sakakawea in Rodeo, Government and Pochant bays.

“The salmon move into the shallows to spawn, but since there aren’t any streams for them to spawn naturally, they just cruise along the shoreline in the back of the bays and we collect them with electro-fishing gear,” Kinzler said. “After we collect the salmon, they are hauled to the hatchery where their eggs are taken, hatched and raised over winter.”

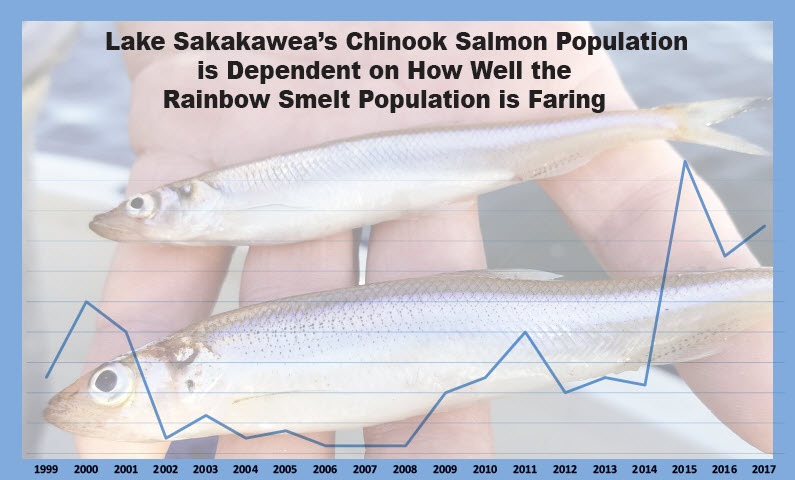

The recipe for a healthy chinook salmon population in Lake Sakakawea is, when you boil it down, pretty simple – water and rainbow smelt.

Rainbow smelt were stocked in Sakakawea in 1971 to improve the lake’s forage base. While small individually – smelt seldom grow longer than 12 inches – the smelt population as a whole is made up of millions of individual fish.

Greg Power, Game and Fish Department fisheries chief, said adult smelt need deep, coldwater habitat during the summer months to survive. For this reason, the Department’s standing recommendation to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for Sakakawea is a minimum elevation of 1,832 feet above mean sea level.

“We have met that minimum elevation for nearly 10 years, which is a great thing,” Power said. “In the years we are below that target elevation in the summer, we can expect high mortality of adult rainbow smelt.”

To get adult smelt, you first need a successful spawn. Smelt spawn in the shallow rocks in the upper half of the reservoir and are susceptible to high winds exposing their eggs and a drop in water levels, leaving eggs high and dry.

“Biologists from Montana, South Dakota and North Dakota have a standing recommendation with the corps to maintain a spring rise at this critical time during the smelt spawn at least once every third year,” Power said.

Fortunately, Sakakawea had a nearly two-foot spring rise in 2014 and again in 2016, resulting in banner rainbow smelt year-classes.

“First and foremost, it’s all about the water, which then makes it all about the smelt, which then makes it all about chinook salmon,” Power said.

It’s all about the smelt when it comes to salmon because the latter, aside from the occasional cisco, preys on little else.

“Chinook salmon are a coldwater predator and they rely on coldwater prey, which in Sakakawea is rainbow smelt,” Power said. “It’s that simple.”

While the salmon fishing in Sakakawea has been fairly consistent the last handful of years, Power said it can go south in a big hurry if rainbow smelt reproduction is interrupted by Mother Nature or human influence.

“It’s happened before and it will happen again,” he said.

Because smelt serve such an important role as forage for salmon and other game fish species, Department fisheries biologists have been tracking their population trends since 1999. The health of the smelt population determines how many salmon will be stocked in spring.

“We look at our hydroacoustic data, which is the method we use to survey the smelt in summer, to determine how many salmon we are going to stock the following year,” Kinzler said.

Jeff Hendrickson, Department fisheries supervisor, with a salmon he caught in mid-August on Lake Sakakawea.

Power said biologists will likely stock roughly the same number of salmon smolts, about 400,000 or so, in 2018 as were released in Sakakawea in 2017.

“When the lake has a lot of water and has a good smelt population like it does now, salmon will be in the 3- to 5-pound range a full year later after we stock them,” Kinzler said. “And the 2-year-olds can reach that 8- to 10-pound range.”

When salmon get to that size, anglers really start to take interest. Which is pretty much what fisheries managers had in mind when they stocked chinook salmon in Lake Sakakawea for the first time more than 40 years ago.