A Look Back

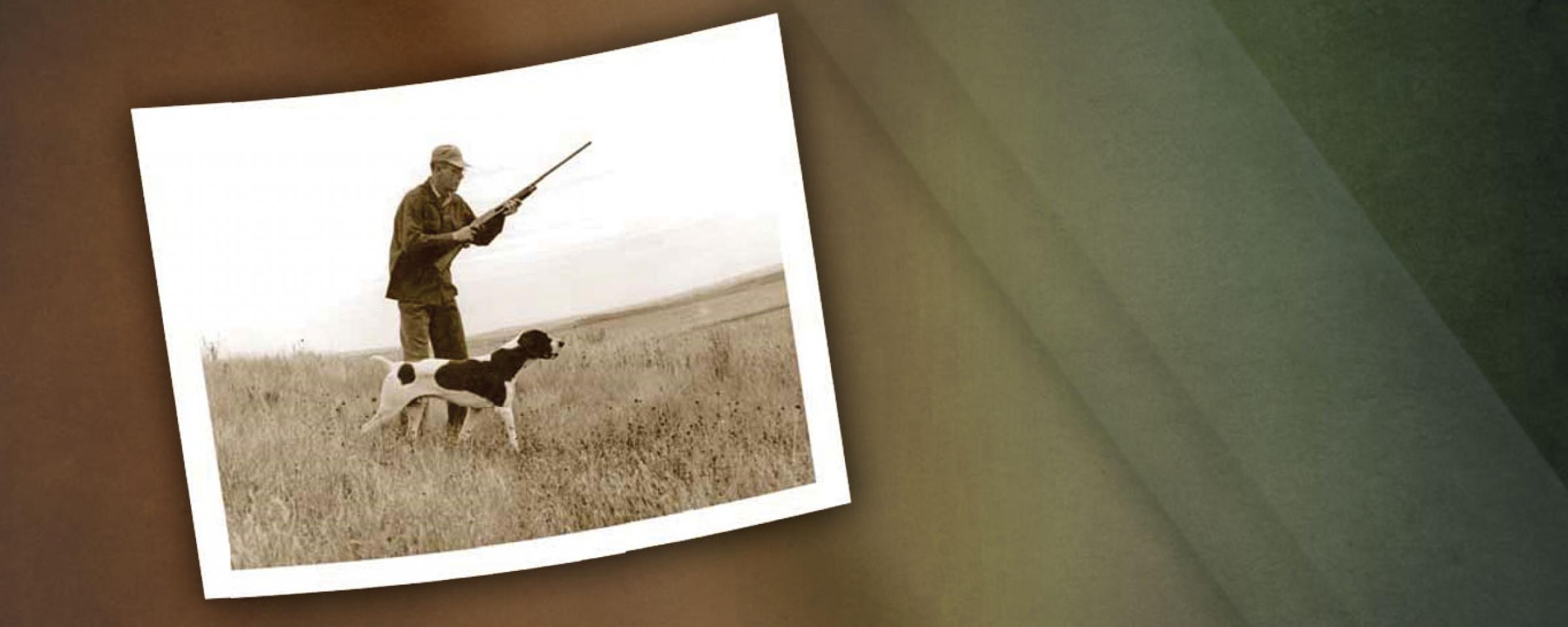

“The hunter and his dog symbolize fall hunting. This month our game birds will offer us many delightful hours afield. Enjoy the sport, but keep in mind the basic rules of safety and observe the rights of others. Ask permission to hunt on private land and you’ll seldom be refused.”

This caption described the cover photograph for the October 1955 issue of North Dakota OUTDOORS. The hunter and his pointer were not identified.

What’s interesting about the photograph that dates back more than 60 years, but would certainly not register a second thought if the photograph was shot today, is the dog’s attendance in the image.

While it’s difficult to wrap your head around it today, there was a time (starting in 1919) when North Dakota lawmakers outlawed the use of dogs for hunting upland game birds.

According to an article in OUTDOORS in 2007, following the decimation of big game populations by the late 1880s, prairie chickens, sharp-tailed grouse and waterfowl were about the only things left to hunt in North Dakota. Up until 1910 or so, prairie chickens seemed an inexhaustible resource, but later in the decade their numbers had dwindled to a point where people demanded action.

The article continued, saying that this same sense of urgency also led to the introduction of ring-necked pheasants and Hungarian partridge, but legislators felt eliminating the use of dogs would reduce harvest and give upland birds more of a chance. The law did not apply to waterfowl hunting.

Following the formation of the North Dakota Game and Fish Department, as we know it today, in 1930, wildlife officials ultimately convinced legislators and citizens that the loss of wildlife habitat was the reason for game bird population declines and that dogs were a conservation benefit because of the wounded birds they could recover.

In 1933 state law changed to allow spaniels or retrievers to retrieve, but not point or flush, upland game birds for hunters. Pointers and setters were still not allowed in the field.

J.E. Campbell, Game and Fish deputy commissioner, wrote in North Dakota OUTDOORS in December 1942:

“… will any right-mined individual put forth just one good and sufficient reason why any sportsman should be deprived of the use of his dog in helping him secure his daily bag limit?”

The answer must have been “no.”

In 1943, when pheasant and partridge populations were impressive and hunting opportunities were plentiful, the prohibition against hunting dogs in North Dakota was lifted.

Doggone right.