A Changing Waterfowl Landscape

As a waterfowl biologist, I often get asked about the prospects for upcoming hunting seasons for ducks or geese.

The answer really depends on the perspective and expectations of the person asking it. Even more complicating is that waterfowl hunting is never really the same on a year-to-year, area-to-area basis.

Cropping patterns, wetland conditions, upland nesting potential, and weather patterns that affect migration are always changing the numbers and types of waterfowl people encounter in an area.

Hunter numbers are also a factor, and while the Game and Fish Department fields a lot of concerns about too many hunters in certain areas, not enough hunters in some areas can also reduce potential.

Changes in North Dakota Waterfowling

As with most things, change in waterfowl abundance and hunting tactics is inevitable. In the 1960s and 1970s, North Dakota had more active waterfowl hunters than at any other time. In 1975, more than 73,000 hunters took to the field in pursuit of waterfowl.

This peak in hunter numbers also took place during a time when just about all waterfowl populations were lower – and in some cases much lower – than they are now. Daily bag limits 40 years ago were generally more restrictive than they are now and seasons were shorter, especially for geese.

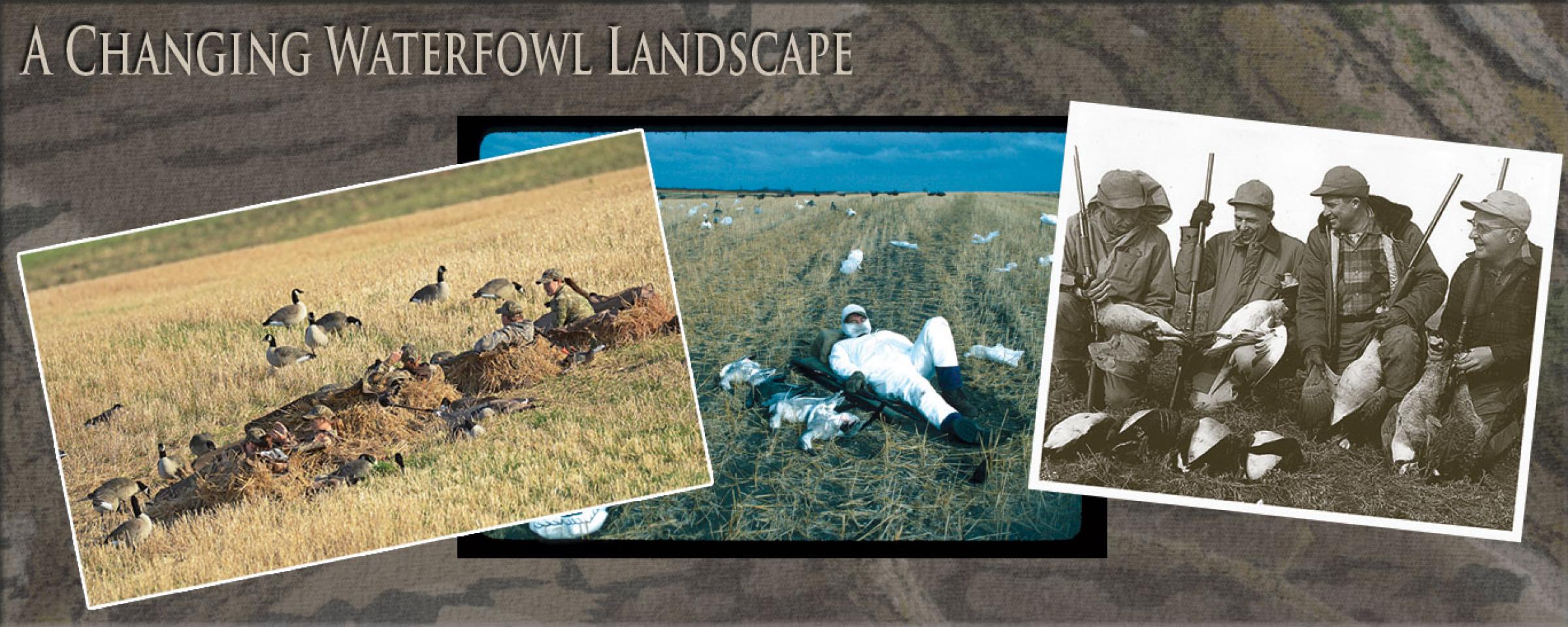

Dressed in drab gear favored by duck hunters some time ago, a hunter hides in the slough-side vegetation from the curious eyes of passing waterfowl.

Back then, snow geese in North Dakota were a much larger part of the show, comprising almost 80 percent of the state’s total goose harvest. The birds were mostly harvested north of U.S. Highway 2 in the north central and northeastern parts of the state. Pass shooting along firing lines was popular and many other hunters took to the countryside to hunt in decoy spreads.

What has changed? Interestingly, I conducted an analysis of band data from snow and Ross’s geese that shows the average recovery date of a band in North Dakota in recent years is 20 days later than it was in 1975. In other words, for every two years that has gone by, the average date of a light goose band recovery is a day later in the season.

How can that be? It seems like we are so confined by a short window of hunting days in North Dakota, you’d think there’s not that much room for change. Several factors, however, have contributed to changes in migration that are influencing goose and duck harvest.

Perhaps the most important change is that cropping patterns are much different than they were 40-50 years ago. In 1975, North Dakota farmers planted a little more than 6 million acres of durum and barley, while at the same time they planted less than 200,000 acres each of corn and soybeans.

This spring, almost 6 million acres of soybeans and 3.5 million acres of corn were planted in North Dakota, while less than 2 million acres of barley and durum were planted.

Why the comparison between these two groups of crops? It all comes down to fueling the migration. During many years, corn isn’t harvested until late in fall, sometimes after the snow flies in North Dakota. That is usually too late to attract large numbers of staging birds, and it’s not always dependable enough if you’re a migrating fowl hoping to find good fuel.

Soybeans are also harvested later than small grains, and they pose another, more significant problem. Unlike young, growing soybean plants, raw soybeans actually contain a metabolic inhibitor that prevents waterfowl from digesting them properly. Basically, waterfowl can eat as many raw soybeans as they want, but they never get fatter, and storing up fat for the long migration ahead is important. Sometimes birds that continue to eat soybeans wind up dying from causes related to near-starvation, but sometimes they also die from impaction of the beans in their crops and digestive tracts. That’s not a good plan if you’re fueling a migration, and the birds know it.

Cropping patterns have also changed in other places. The western prairies of Canada have added almost 5 million acres of pulse crops, such as peas and lentils. Seasoned waterfowlers know how these fields can attract birds, and they are usually some of the first crops harvested. What all of this means is that birds coming from the arctic, or right out of the Canadian prairie, have better resources available right away in early fall, and they can stay farther north until freezing temperatures move them along later in the migration.

Temperature may also have an influence on the timing of birds migrating into and out of North Dakota. In recent years, the average September temperature in central North Dakota has been a little more than four degrees Fahrenheit warmer than it was in 1950. It doesn’t sound like much, but it can really change where waterfowl want to be in the fall; mostly that they can probably stay north longer than before. In most years that means migrating geese spend less time in North Dakota before the harsh hand of winter swings its first blow across the Northern Plains.

Another factor is hunting pressure. Prairie Canada has about the same number of waterfowl hunters as North Dakota in an area that is much, much larger. When birds are not pressured, and they have plenty of food to eat, they often tend to stay where they’re at until weather pushes them out, so the decision for birds to stage farther north prior to departing for Kansas is pretty easy.

These changes in migration patterns might mean that hunters will have to adjust their expectations for what it is they are trying to accomplish.

A trend that I’ve seen the past 10-15 years is that more and more waterfowlers in the Great Plains are using tactics that employ large decoy spreads in fields. That kind of hunt can be a ton of fun, especially if you are set at the “end of the rainbow.”

However, those situations are few and far between and are getting more difficult to find in North Dakota. And when you do find one, there are often two or three other groups in the same area searching for that same kind of experience.

With certainly more options in hunting equipment today, many waterfowlers leave little to chance and dress from head to toe in camouflage.

The bottom line is, hunters who want to have successful hunts on a more consistent basis may need to look at diversifying their tactics, the areas they hunt, and even the types of waterfowling they pursue.

It is sometimes hard to reconcile that North Dakota in recent years has experienced changes in attracting and staging waterfowl in the state when, on a continental scale, duck and goose hunting opportunities look so good. We’ve had about 45,000-50,000 regular season waterfowl hunters each year in North Dakota since about 2006, and most waterfowl populations are at or near historic highs, especially geese.

On one hand, some areas have too many nesting geese, while other areas struggle to maintain quality habitat for nesting ducks. As a result, harvest opportunities for geese have become ultra-liberalized, going from limited opportunities for Canada geese to hunting them for parts of five or even six months in some years, with large daily bag limits.

While duck hunting in the state has remained good and limits have remained liberal for the past two decades, we have become more reliant on our own locally produced birds due to changes in migration patterns. It makes it even more important to ensure that North Dakota continues to produce ducks.

So when someone asks, “Will it be good this year?” I usually need to ask more questions to figure out if they are expecting to wind up with 30 greenheads and a row of geese laid out across several lay-out blinds, or if they are generally asking if there are good numbers of birds and decent hunting conditions.

We can set the stage for expectations on habitat and populations, but hunters almost need to think about what they’re really expecting. North Dakota will have good duck and goose populations this fall, and plenty of hunting opportunities. Whether that leads to a successful season for each individual, we’ll know in a couple of months.