Grassland Birds

It’s early June and a few minutes past sunrise in western North Dakota, about 5 a.m. Mountain time. The field crew of eight is weary eyed and the caffeine is slow to kick in.

Kelsey Bell, with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, carefully untangles a grasshopper sparrow from a net.

Yet, the other life out here is wide awake, exuberant and ready for another day of defending their chosen patch of prairie. A high-pitched insect-like song – tik tuk tik-a-zeeeeeeeee – radiates from one direction, then another, and another farther away. Then a more musical song, with a slight tinkle tone – tik a-tl-tleeeeee – advertises nearby.

We get to work setting up two mist nets, made of fine nylon mesh that resemble a volleyball net, suspended between two poles. An electronic game call is placed below the net, but instead of hearing the usual jackrabbit distress for coyote hunting, the two grassland bird songs we hear around us start playing.

Within minutes, a brown object flitters low across the grass toward the game call. A few feet from the net it hesitates slightly, but the will to defend its territory is too strong. Into the net it flies, tangling in one of the loose mesh pouches. Two field crew members rush the net and gently grab the bird, disentangling it from its hold.

“Is it banded?” asks one crew member. “Nope” says another. We are in nearly the same spot on the prairie as last year where biologists from Bird Conservancy of the Rockies trapped grasshopper sparrows and Baird’s sparrows, and outfitted them with tiny geolocators.

These devices store data on light levels, which can then be used to calculate latitude and longitude, and produce a map that shows the sparrow’s migration route. The hitch is the bird must be caught and the geolocator removed to retrieve the data.

Kaitlyn Wilson (left) and Kelsey Bell, both with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, assemble a mist net.

The bird caught in the mist net is a male grasshopper sparrow. Since he is wearing nothing, he will get fitted with a lightweight geolocator, which is sort of a tiny bird backpack, a numbered metal band on one leg, and a colored plastic band on the other. Maybe next year, in this same exact spot on the prairie, he will return and the researchers will catch him again and find out where exactly he’s been.

This is just one piece of a much larger project to understand the full annual life cycle – breeding, wintering, and migratory behavior – of grassland nesting songbirds.

Grassland dependent birds, such as Baird’s and grasshopper sparrows, Sprague’s pipit and chestnut-collared longspurs, have declined more than other guilds of birds. One obvious reason is loss of grassland habitat, particularly native prairie in the breeding grounds.

Some grassland birds, such as grasshopper sparrows, are more generalists and aren’t as picky about the type of grass they seek. They are found equally in native prairie or planted grassland such as CRP. Others, like Baird’s sparrows and chestnut-collared longspurs, will pretty much stick to native prairies, particularly grazed pastures.

Yet, there is a lot we don’t know about these birds that may also be factors in their decline, such as annual productivity, nest success, juvenile survival and adult survival. This demographic information is important because it will help scientists understand where populations may be most limited, even if the habitat is available.

A mist net, teamed with a game call, is used to catch unsuspecting grassland birds defending their territory.

In 2015, the North Dakota Game and Fish Department provided State Wildlife Grant funding to Bird Conservancy of the Rockies to study grassland nesting bird demographics at sites in far western North Dakota.

Field crews conduct nest searches by dragging a nylon rope through grass to flush incubating birds, or use behavioral cues to find nests. The nests are monitored every one to three days to estimate daily survival rate and nest success (i.e. how many nests fledge at least one young). When young are nearly ready to fledge, they are fitted with miniscule radio transmitters and are tracked at least once a day to determine if they die or disappear.

Adult birds are also caught using mist nets and audio lures, fitted with radio transmitters, and tracked daily to determine if they survive the nesting season. And if they don’t, researchers try to verify the cause of death.

It’s not easy growing up on the ground, as there are lots of predators, such as snakes and 13-lined ground squirrels. Field crews have tracked transmitters underground and dug up burrows containing a cache of the devices, banded legs, and other nestling bird body parts.

Other factors, like weather, can play a huge role in survival. Last year, it got terribly dry around the field sites and insects were tough for adult birds to find to feed their young. Researchers surmised that many fledglings died from starvation.

Tim Wuebben, with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, tracks grasslands birds outfitted with transmitters.

This year marks the third year of research in North Dakota. The Bird Conservancy has also initiated demographic monitoring and geolocator deployment at a study site in Montana, and with partners in Alberta, Canada, as well. Furthermore, the Conservancy has been monitoring these birds on wintering grounds in the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands in Mexico, to better understand winter survival rates and if populations may be limited during winter. Another piece of the full annual life cycle mystery.

Back on the breeding grounds, we hear on the radio: “I’ve got a banded Baird’s over here.” We each pick up an end of a pole, with the mist net waving in between, and march over the hill about 100 yards.

One of the crew has spotted a colored leg band on a Baird’s sparrow. It’s a geolocator tagged bird from last year. We quickly get set up, hunker in the grass, and watch as the bird darts from grass clump to grass clump. The audio playback is not enticing him and all we can do is watch him fly away. The crew marks the spot and will try catching him another day.

We keep moving the nets, catching new birds, sending them off to get fitted with their new bling, when we finally spot another color banded bird. “I can see his geolocator,” a researcher yells. We move the nets to his territory and in a few minutes we’ve caught a tagged bird.

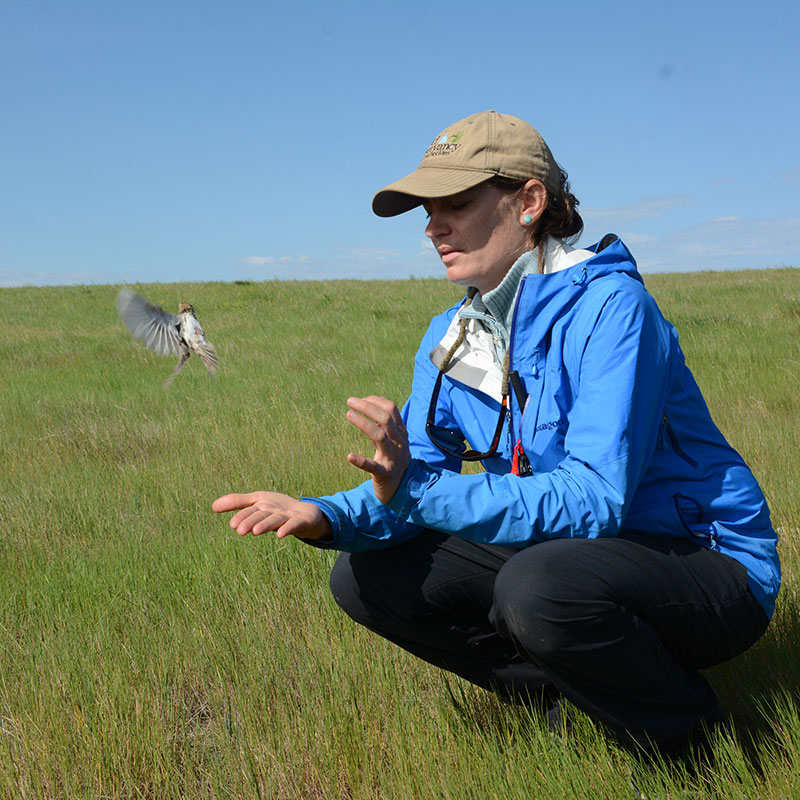

Erin Strasser, with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, releases a sparrow.

This male grasshopper sparrow was caught in almost the same exact spot on the prairie of western North Dakota as he was nearly one year ago. In late summer/early fall he left the state, heading south through the Central Flyway, and like a snowbird, spent winter somewhere in the warm desert grasslands of the southern United States or Mexico.

Now that his geolocator has been recovered, researchers will analyze the data and find out exactly where he’s been and if he stopped anywhere along the way. Knowing this will help identify areas that are important to the birds to rest and refuel during the long journey.

It’s an amazing feat, this long migration from, say, Mexico, to nearly the exact spot on its summer grounds in western North Dakota. It’s especially remarkable for a bird that weighs about a half-ounce.

More on Grassland Birds

For more information and to watch a video about the project, see https://gf.nd.gov/wildlife/swg/project/t-46-r

To learn more about the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, see http://www.birdconservancy.org/.