Sage Grouse Recovery Effort Underway

State wildlife managers are hoping a unique sage grouse translocation project will bolster a population of birds in southwestern North Dakota that’s been staggered over time.

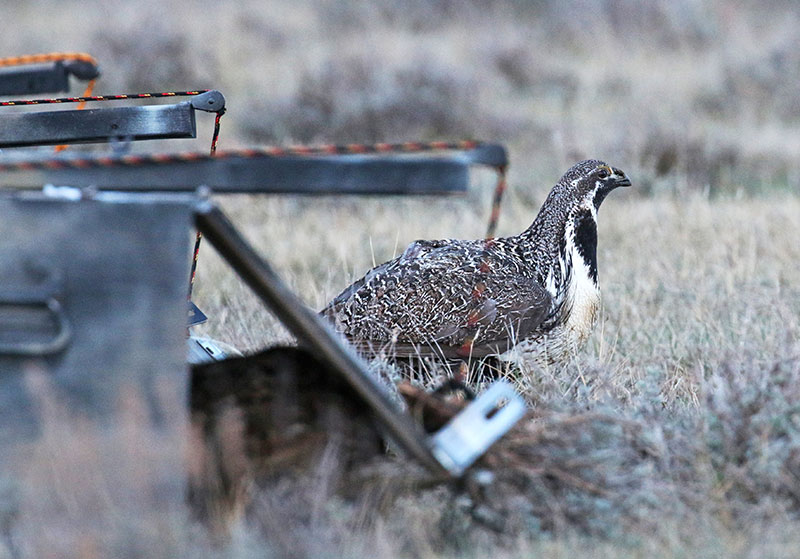

A sage grouse eases out of the release box onto a lek in North Dakota.

In April, North Dakota Game and Fish personnel moved 60 sage grouse – 40 females and 20 males – from southern Wyoming to Bowman County. To keep tabs on the birds, all were marked with either GPS or VHF radio devices.

“We have to manage people’s expectations,” said Aaron Robinson, Game and Fish Department upland game management supervisor in Dickinson. “Just because we introduced 60 birds to southwestern North Dakota doesn’t mean the sage grouse population is now stable.”

Even so, Robinson said it’s imperative to try to help the species rebound.

“‘We need to be able to look ourselves and the public in the eye and say, and know for certain, that we did everything we possibly could,” he said.

Living on the Edge

Sage grouse in southwestern North Dakota are on the eastern edge of their range, where habitat and weather limit their success and expansion.

Sage grouse decoys were used to help the newcomers feel at home.

The big upland birds have a fundamental link to the aromatic plant, big sage. Sagebrush is critical to sage grouse, as they rely on the plant for food for much of the year, cover from weather and predators, and nesting and brood habitat.

The reality, however, is about half of the big sage habitat in North Dakota has vanished from the landscape in the last half-century, but has remained stable for the last decade or more.

The state’s sage grouse population, even a number of years ago when the birds were at their peak here, has never been considered high in comparison to other states, like Wyoming and Montana.

While efforts to improve sagebrush habitat are ongoing, the decline in sage grouse numbers in the last decade or so in North Dakota is credited in part to West Nile virus. The population was especially hard hit by the virus in 2007-08.

North Dakota had its first sage grouse hunting season in 1964 and it was closed just once, in 1979, before being shut down indefinitely in 2008. The season, a three-day hunt the bulk of those years, never attracted many hunters, maybe 100 or so annually.

Jaden Honeyman, Department private land biologist, unloads sage grouse flown in from Wyoming.

Following troubling declines in sage grouse numbers in 11 Western states, North Dakota included, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced in 2015 the species didn’t need protection under the Endangered Species Act, considering threats to sage grouse had since been significantly reduced across much of the species’ breeding habitat.

Among other efforts over the years to benefit sage grouse in North Dakota, the Game and Fish Department worked with USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management on sagebrush plantings to connect fragmented areas, protect the sagebrush habitat that remains, and provide incentives to landowners to introduce grazing practices that increase residual grass cover that benefits sage grouse.

Anchoring in North Dakota

Graduate student, Kade Lazenby, will monitor the sage grouse over summer.

After capture in Wyoming, the birds were put individually into boxes and flown to North Dakota, where, with as little fuss as possible, quietly released on a lek in Bowman County.

“Flying the grouse to North Dakota worked really well, as it helped minimize the stress on the birds and limited their exposure to people,” Robinson said.

Robinson said there are two types of releases – soft and hard – when reintroducing animals back into the wild. Biologists used the former with the sage grouse in North Dakota, by placing the boxed birds on the lek overnight before their doors were quietly opened early the following morning.

“With a soft release, you want the grouse to get accustomed to their new surroundings,” Robinson said. “So when it’s time to release them, they’ve calmed down, and hopefully stick around when they walk out onto the lek.”

Then again, Robinson said sage grouse are a difficult species to recover and handle because of their need and want to return to their old turf.

“We took these birds from sage grouse habitat in Wyoming that is as beautiful as you’ve ever seen … all you can see on the horizon is the Rocky Mountains and sagebrush in between,” he said. “I’m sure coming to North Dakota is a shock to their system.”

Sixty sage grouse were captured in Wyoming and released in North Dakota.

Many of the GPS- and VHF-marked birds that biologists are tracking have moved, in some instances, great distances.

“There are birds moving all over … into South Dakota, Montana and back,” Robinson said. “It was not unexpected, but when you see the size of some of their movements, it’s pretty astonishing.”

Before their release, a sample of the females were artificially inseminated, with the hope that they’d nest in southwestern North Dakota. To get some of the females, even just a few, to initiate a nest, would likely anchor them to North Dakota. And, in turn, do the same to hatched young.

“If we can get a female to initiate a nest and raise at least one chick, then that chick is now part of North Dakota’s population because of the young bird’s fidelity to the site,” Robinson said.

Robinson said that while it’s too early to write the bird’s eulogy in North Dakota, patience is required as the recovery effort will take time. Next year, with minor adjustments to the translocation process where hiccups occurred in 2017, the plan is to move the same number of birds from Wyoming to North Dakota.

In the interim, a graduate student from Utah State University will keep tabs on the newcomers to see if they adjust to North Dakota, rear young and hang around.

In late April, the marked female sage grouse had yet to show signs of initiating nest sites, but it was early yet.

“Hopefully in the next couple weeks they’ll slow down their movements and start initiating nesting,” Robinson said. “If we could just get a couple of females to do that, then it’s a start.”