Diary of a Wet Cycle

Blowing dust from dry alkali wetlands sometimes looked like a snowstorm during the drought of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Twenty five years ago this month, this magazine published a story outlining a new initiative in the Game and Fish Department’s fisheries division called “Priority Lakes.” It outlined a plan to “…redirect fisheries management efforts to lakes that have the most potential as long-term fisheries.”

At the time, in early summer of 1993, North Dakota did not have very many lakes, outside of the Missouri River System reservoirs, Devils Lake, a couple of dozen larger reservoirs and some larger natural lakes, that had solid potential as long-term fisheries.

Priority Lakes came about after an honest assessment of what 5 years of drought had done to the state’s fishing resources. Of about 180 fishing waters in the state at the time, Game and Fish was going to focus its efforts on 60 of them, “…until water levels return to normal.”

How many years it would take for that to happen was anybody’s guess.

And then, just as thousands of subscribers were pulling their July 1993 North Dakota OUTDOORS magazines from their mailboxes and reading about this new fisheries plan, it started raining. Not just one timely “boy-we-sure-needed-that” rain, but a series of multiple-inch downpours that flooded streets in many cities and creeks and rivers across the countryside.

When prairie wetlands go dry for extended periods, vegetation grows up, making for a more productive setting when water returns.

By the time July 1993 ended it was, and still is, the wettest month in North Dakota’s recorded history. Bismarck had nearly 14 inches that one month, and other locales had even more.

In just 31 days, water levels in many existing fishing lakes across the state were well on their way back to normal. The Priority Lakes plan that was intended to focus on existing waters became more of plan for developing revitalized and eventually new lakes. And no one in the fisheries division seemed to mind that at all.

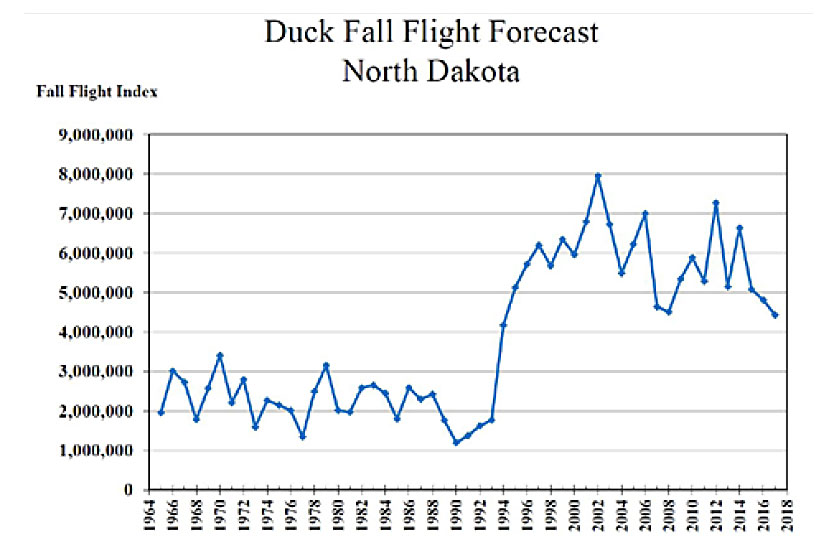

Similarly, the state’s waterfowl situation improved markedly almost overnight and kept building along with water levels. Starting in 1994, the Game and Fish Department’s fall duck flight forecast of birds produced in the state, based on counts from the annual midsummer duck brood survey, has come in above the long-term average in every single year since.

The North Dakota fall flight estimate went from a near-record low of just over 1 million birds in 1990, to an all-time high of about 8 million birds in 2002.

To put in perspective what this wealth of water meant, however, it’s important to consider the dried-out landscape that desperately needed it.

Dire Straits from Drought

June 1988 was the hottest June ever recorded in North Dakota up until that time. Temperatures were 8-12 degrees above normal. Both prairie grass and crop fields turned brown.

That was probably the worst month and year in a 5-year stretch of dry years that got started in fall 1987. But the following summer, July 1989 was either the second or third hottest North Dakota July on record, depending on location.

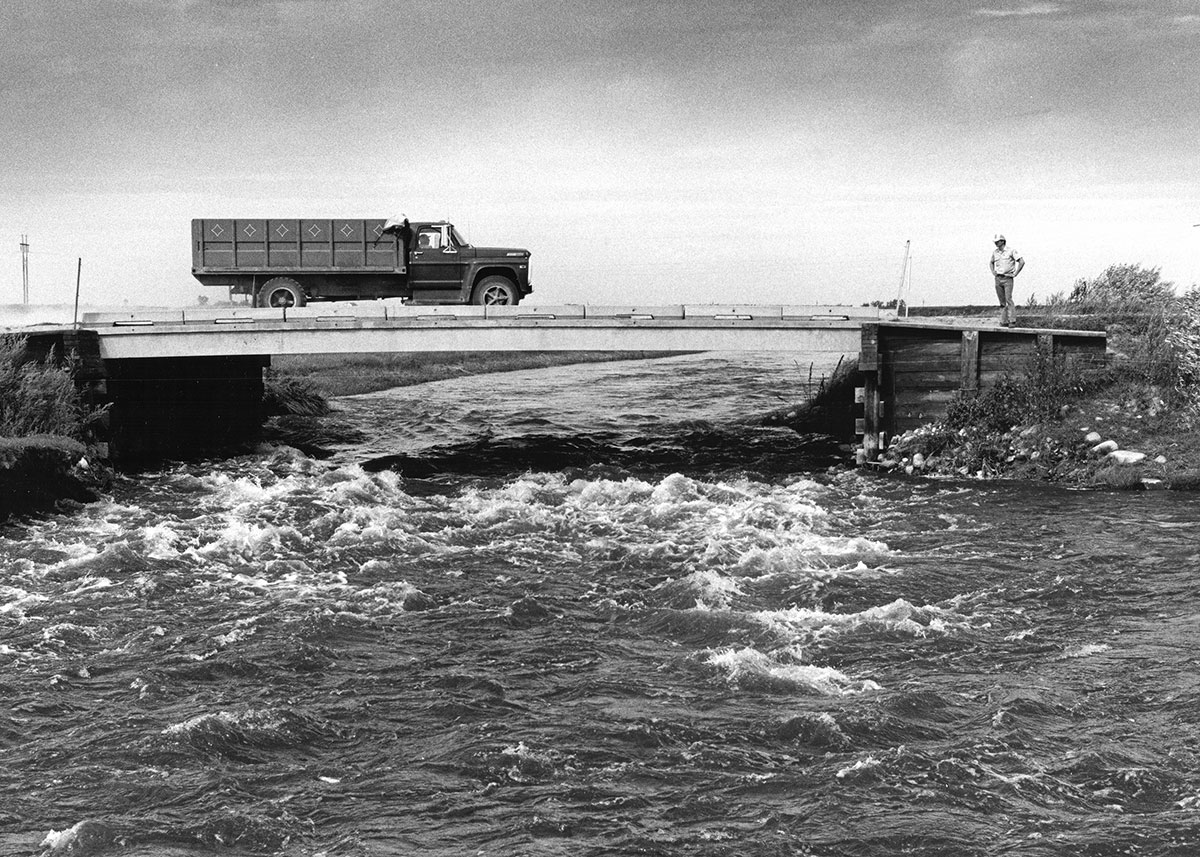

This boat ramp at Beaver Bay on Lake Oahe was representative of most high water ramps on the Missouri River System in the early 1990s before the drought broke.

A story in the August 1990 issue of North Dakota OUTDOORS chronicling the first two years of that drought noted: “During the drought, North Dakota had the distinction of leading the nation in the amount of land damaged by wind erosion.”

Like the summer of 2017, the summer of 1988 was not kind to upland bird reproduction efforts. Pheasant, grouse and partridge harvests in 1988 all fell considerably from 1987.

On the other hand, better but still dry conditions over the next few years helped pheasants and partridge that were also getting a boost from hundreds of thousands of acres of newly emerging Conservation Reserve Program grasslands that North Dakota landowners eagerly enrolled at a time when most crop prices were low and production was influenced by ongoing dry conditions.

On the waterfowl side, the lowest wetland index ever in the Department’s spring breeding duck survey, which started in 1948, occurred in 1990, and that still remains the record low.

The second lowest number of breeding ducks ever counted in the spring survey, occurred in 1991.

Starting in 1988, the daily duck limit was cut to three, and it stayed that way until 1994. The duck season was shortened to 30 days and shooting hours started at sunrise instead of a half-hour before. It was indeed a dire time for not just North Dakota, but continental duck populations.

On the fishing side of things, in spring 1989 Lake Sakakawea had only one useable boat ramp at ice-out, and Lake Oahe didn’t have any.

From 1988 through 1992, the water level at Devils Lake fell more than 6 feet, leaving previously flooded trees high and dry, and putting part of the lake at risk for significant winterkill.

Devils Lake was receding to a point where winterkill became a concern. Devils Lake was also at the time the most important source of walleye and pike eggs, and traditional areas where spawning nets were set were no longer available because of low water. In spring 1990, Game and Fish couldn’t come up with enough walleye eggs to meet hatchery needs, and for the first time, received surplus eggs from Minnesota and South Dakota.

And here’s an indirect influence of the dry times on some southern North Dakota fishing lakes, written by then southeast district fisheries manager Gene Van Eeckhout in his annual report in the January 1990 issue of OUTDOORS:

“But early in 1989, I recorded deteriorating water quality. Like 1988, there was very little runoff so why the difference? In the process of collecting water samples, my anchor dragged across the bottoms of several ponds. When lifted to the surface, there were large amounts of ‘kochia weed’ and ‘Russian thistles’ attached to the anchor. Recollect if you will the windy weather we had last spring and all the ‘tumbleweeds’ blowing around. Many tons of these obviously ended up in our lake basins, where, through decomposition, they have added nutrients and consumed oxygen.”

At least one small town in south central North Dakota that spring had to bring out a snow plow to push drifted tumbleweeds from its main street.

Hardly a magazine went by during the early 1990s that didn’t have some kind of negative report related to low water levels. Fisheries biologists netted game fish out of Crooked Lake in McLean County and moved them to Lake Audubon because of an anticipated fish kill in the 1990-91 winter.

One of the remarkable things about the current wet cycle is how high water levels have advanced in some locales. Some farmsteads and homes were flooded in places that had not experienced similar water levels in well over a century.

Liberalized fish limits were implemented on other lakes that seemed destined to the same winter fate. In April 1990, then Game and Fish Director Lloyd Jones simply wrote: “We need water soon.”

But amidst all the negativity, there was hope. Dry shorelines became fertile growing grounds for vegetation, both on lakes and wetlands, and biologists knew that IF water ever came back to flood that new vegetation, the news would get better. “We’re poised for a population explosion when water levels returned to normal,” said one fisheries biologist in 1990.

No one expected that turn-around to come in such impressive fashion. Almost overnight, the tone changed. Stories reflected all the good things that were anticipated with the newly accumulating water. Most of them came true. Some of them exceeded anyone’s expectations.

After the Rain: The First Cycle

By the end of summer 1993, Lake Sakakawea’s water level rose 15 feet, immediately improving the access issues that were prevalent for 5 years.

Devils Lake came up 5 feet by September that year and kept rising, which eventually led to widespread flooding problems, but in that first year solved the winterkill threat and revitalized fish spawning grounds.

Water gushing into Devils Lake via Channel A in September 1993 helped raise the lake level more than 5 feet at the time. In the 20 years after that, Devils Lake came up another 25 feet or so, flooding roads, home, cabins and farmland, but also establishing a world-class fishery.

But one month, even one summer of record precipitation by itself wouldn’t have been enough to make viable fishing waters out of dry alkali flats. The following winter of 1993-94 was cold and produced near-record amounts of snow in some places.

A few years later the winter of 1996-97 also brought record or near-record snow over much of the state, adding to the margins of wetland basins large and small.

Average annual precipitation for Bismarck is about 16.5 inches. Starting in 1993, that average was topped eight times in 10 years. In addition to 1993, which was the third wettest year in North Dakota recorded history up until that time, 1998, 1999 and 2000 were also among the top 10 years of all time for precipitation measured at Bismarck.

Fast-forward to the end of that decade, and the Department’s fisheries division was managing more than 300 lakes compared to around 180 10 years earlier. And those new lakes were incredibly productive fisheries for perch and northern pike. “Before the water came back, some of these perch lakes didn’t exist,” said Greg Power, now the Department’s fisheries chief, back in 2003. “Dry Lake (McIntosh County) went from a deer meadow to a 30-foot-deep lake and, for a few years, was a world-class perch fishery.”

The difference in the fall duck flight forecast from North Dakota following the summer of 1993 is striking.

That wasn’t all. Power went on to say that during the winter of 1999-2000, four of the top five lakes hit by ice anglers pursuing perch were new waters that were mostly dry or shallow basins in spring 1993.

“We feel safe to say that, in geological time, we have never had so many pike and perch in the state,” Power added. “There have never been so many fishing opportunities …”

Not surprisingly, fishing license sales also perked up, peaking for that time at about 140,000 resident licenses in 2000, compared to about 100,000 in 1992, and Power said people who did fish were going out more, because the fishing was better.

Interestingly, Power also spoke of the progression of some of these new lakes to where they had reached a peak and were losing productivity.

It didn’t take long for tremendous perch fishing to develop on revitalized or new fisheries. These nice fish from Dry Lake in McIntosh County were caught in winter 1997, just 4 years after the lake started refilling.

On the other side of the water coin, biologists recorded the all-time peak in water areas during the spring breeding duck survey in 1999. Breeding duck numbers that year were about six times higher than in 1990. A lot of that was due to most wetland basins in the state having water again. But the CRP grassland in prairie pothole country was also a significant benefit. CRP provided hundreds of thousands of acres of large tracts of nesting cover, and the combination of water and grass jumpstarted North Dakota duck production potential.

“We had the recipe in place for ducks to be successful in North Dakota,” now retired waterfowl biologist Mike Johnson said in 2003. “And since we get quite a bit of homing, the birds were surviving, and coming back year after year. We were able to build on that.”

Resident Canada goose numbers also hit that new water running, so to speak. The new water provided habitat for muskrats, and muskrats built new houses, which provided countless nesting spots for resident geese. No longer did they mostly rely on nesting tubs and haybales placed near the few wetlands that held water.

The North Dakota breeding population has increased significantly since then.

Hard Times on Huns

While a lot of good things happened with North Dakota wildlife and fisheries following July 1993, the state’s Hungarian partridge population went the other direction, and it hasn’t really recovered.

Like the pheasant, an introduced bird, partridge had reached somewhat of a peak population in the early 1990s as they took advantage of new CRP and the dry conditions. The fall harvest topped 200,000 in both 1991 and 1992, which were the highest statewide harvests since the early 1960s.

Along with the excessive rainfall that one month 25 years ago, it was also one of the coolest summers on record. In southwestern North Dakota night time temperatures dipped into the 40s on several occasions and even the 30s a few times. It was a disastrous scenario for newly hatched partridge chicks that need warmer temperatures during their first 10 days or so of life.

This outcome was reflected in brood observations later that summer that were down 70 percent from the previous year. Hunter harvest during the fall of 1993 fell more than 60 percent.

Partridge took another hit during the severe winter of 1996-97. By fall that year the harvest was just 27,000 birds, a decline of nearly 90 percent in just 5 years.

The Second Wave

Starting in 2001, things went the other direction for awhile. By 2003, many fishing waters around the state were starting to recede and winterkill became a concern again.

Eventually, some large “new” fisheries, like Horsehead Lake in Kidder County and West Lake near Napoleon in Logan County, did sustain heavy winter losses by about 2005 and 2006.

Lake Oahe pretty much dried up into the old Missouri River bed, and Sakakawea reached its lowest level since water filled up behind Garrison Dam in the early 1960s. Temporary low-water boat ramps were again the norm for several years.

Duck production increased remarkably even in the first year that wetland basins started filling. From spring 1993 to spring 1994, the number of breeding ducks in North Dakota doubled, and then had doubled again by spring 1997 .

In the second wave of the wet cycle, it wasn’t so much record summer rains that got things going, but rather a long cold snowy winter. While the Missouri River System water levels had started to creep up earlier in 2008, winter 2008-09 started early and stayed late. Snowmelt produced formidable floods that spring all across the state, but part of that runoff went into fishing lakes and wetlands.

Game and Fish Director Terry Steinwand wrote in his Matters of Opinion column in March 2009: “After we’ve fought floods and other fallout from winter, there is a bright side to the story. Low lakes will be replenished and those that were good fisheries in the past have the potential to regain that status.”

From a high point of about 325 managed lakes in 2003, that number had dipped to 285 by the spring of 2008 because of lowered water levels.

In spring of 2009, lake numbers started going the other direction, and then winter 2010-11 and the subsequent spring produced enough snow and rain to generate epic floods on many rivers and wetlands, overflowing roads in many places in the state.

It was more water than anyone would ever want to see at one time again, and by midsummer many fishing waters in the state reached historic high water levels.

In July 2013, 20 years following the first days of the wet cycle, fisheries chief Greg Power said, “Today, we have surpassed even where we were then … Never in North Dakota has there been more water bodies, pike lakes, walleye lakes … We might not be where we were in terms of perch, but that’s only because of predators like pike and walleye.”

Winter and spring 2013 were wet as well. Fisheries management section leader Scott Gangl added in that same article in 2013, “Through experience we have learned to take advantage of what Mother Nature provides. By the end of last summer as we lost 2 feet of water in some of our lakes, we thought, ‘Yep, it’s over … it was good while it lasted.’ But this spring was terrifically wet and some of those lakes are higher than they’ve ever been.”

Those ups and downs are what makes a one-month phenomenon 25 years ago into a cycle.

In spring of 2018, the state now lists more than 425 managed fishing waters, an improvement of more than 100 in less than a decade and about 300 more viable fishing waters than in 1993. Water levels have come down from peak levels a few years ago, but that was the case 10 and 15 years ago, too.

The cycle, with its inherent peaks and valleys, is surpassing 25 years now. No one knows which direction we’ll go from here.

But we can look back and marvel at how much fishing and waterfowl hunting opportunities have improved since the skies first opened up in July 1993.

One Remarkable Day in a Memorable Month

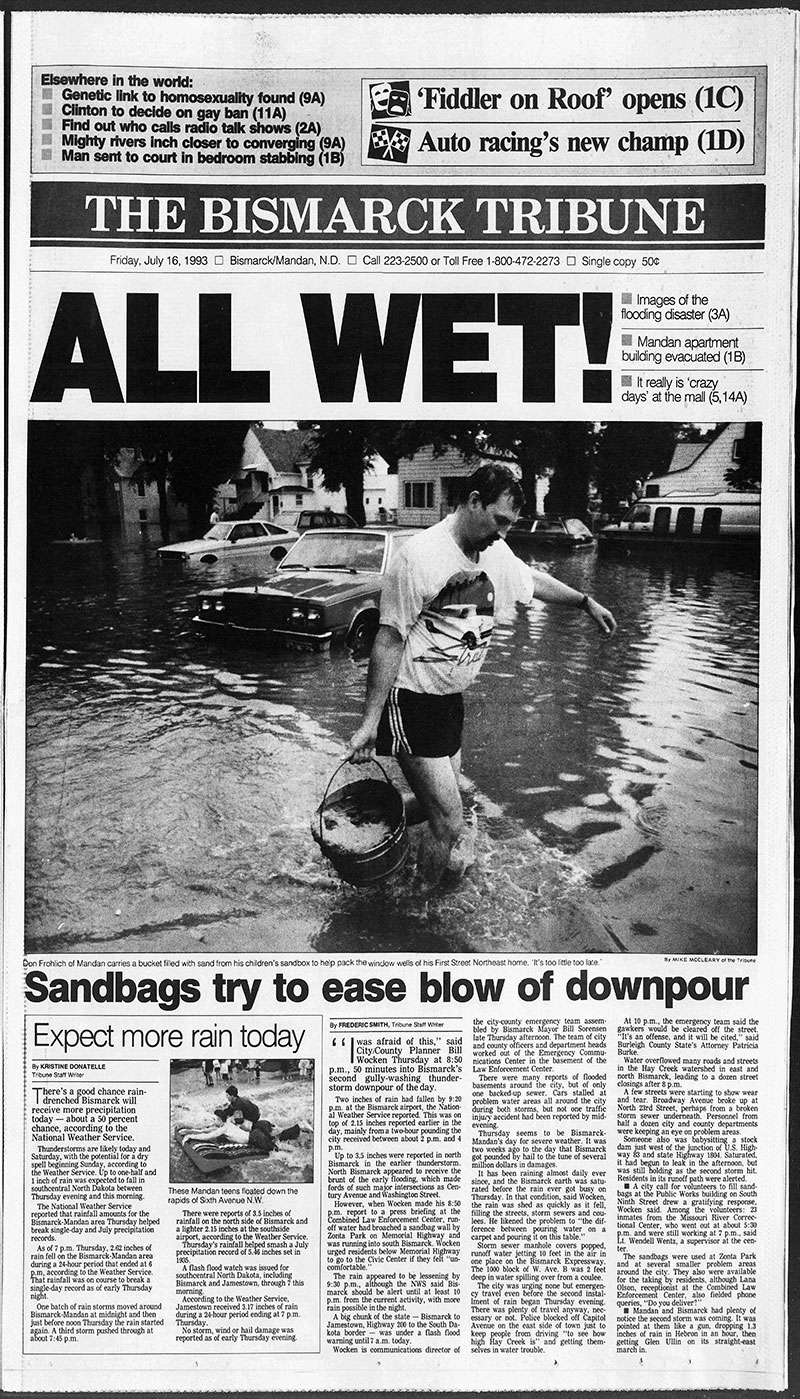

The front page of the Bismarck Tribune on Friday, July 16, 1993 highlighted only a small portion of the stories generated from record rainfall the day before.

In a month that is still the wettest in North Dakota recorded history, one day stands out – Thursday, July 15, 1993.

In mid-afternoon that day, from the south facing windows of the Game and Fish Department headquarters office building in Bismarck, you could see the low dark clouds approaching. At a time long before the internet provided real-time radar to allow people to assess the severity of approaching weather systems, it was obvious this one wasn’t your run-of-the-mill thunderstorm.

It eventually dumped 2-3 inches of rain over Bismarck. This was on top of almost an inch from a storm that moved through after midnight that day. And then another round of storms moved in during the early evening and let loose another 2 inches or so.

By the time it was all over, Bismarck had a 24-hour rainfall record, and a record for rainfall in July with half the month still to go. Streets were flooded to the point that in places cars were half-submerged and teenagers rode air mattresses down streets turned into temporary river rapids.

And then it rained another inch the next day. By the time July 1993 was over, Bismarck had more than 13 inches of rain during a month when more than half the days produced measurable precipitation.

And it wasn’t just Bismarck. Much of the state absorbed multiple inches of rain from that July 15 storm system in what was already a wet month.

Actually, pretty much the entire Missouri-Mississippi river drainages had epic summer floods that year.

By the end of the summer, a section of the state from Powers Lake to Ashley to Jamestown and points east were sitting at more than 10 inches above normal precipitation for that time of year.

By the time things started to dry out in September that year, much of prairie North Dakota was a different place. It still is, because of what got started on that one day.