The snow is falling up. And down. And sideways.

A brisk, northerly wind sends snow streaming toward my living room window. Fat, glittering flakes hang suspended in the air. Suddenly, a southerly crosswind whistles between the neat rows of houses and sends snow soaring off my neighbor’s roof. The snowflakes bob and weave, then shoot skyward as the two air streams collide. Caught in a swirling vortex, the sparkling snow flutters down, pauses, then wobbles upward again, the cycle repeating over and over, as if it’s on a timer. The gleaming ice crystals churn and roll, catching the midday light like a thousand fireflies. It’s like being inside a snow globe.

I’ve lived in the northland my entire life, and I’ve never seen snow like this. This is TV movie snow, cheesy car commercial snow, the too-pretty-to-be-real kind of snow that makes Midwesterners roll their eyes because we know snow and it’s not this. This is the snow of a thousand cliches. I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t seen it.

But I did see it. And while it’s possible that this kind of winter precipitation never occurred in my presence, I think it’s more likely that I never saw snow like this because I simply wasn’t paying attention.

Attention is powerful. And humans aren’t always very good at using our attention effectively. Thankfully, this skill gets stronger with practice. If I hadn’t been staring up at snowflakes, trekking through the woods and traversing frozen prairie for two winters in a row, I might have missed the wonder in my own back yard.

Learning to see

The first step in paying attention is overcoming our basic biology. It turns out that we tune out most visual stimuli. It’s an evolutionary adaptation to help us spot predators, find food and monitor potentially dangerous changes in the environment.

“Rather than try to process everything we see, our eyes stop spending time taking in information from those parts of the environment that hold steady,” explains Barnard College and Columbia University professor Alexandra Horowitz in her book “On Looking: Eleven Walks With Expert Eyes.” “Staring at your computer screen, or the book in your hand, your eyes quickly stop processing all the details of the monitor or the corners of the pages in depth. If something changes, sure, the eye darts to it and neurons fire away. If nothing changes, those neurons can go quiet.”

Winter is quiet. There isn’t much darting around to capture our attention. There are no buzzing bees or fluttering butterflies, no rushing water or rustling leaves to make us stop and listen. Most of the birds have migrated south. Beavers snack under the frozen surface of the ponds and snapping turtles tuck themselves into the mud for a long winter’s nap.

Winter isn’t showy. Its color palette is muted. Summer’s vibrant shades fade into tundra tones of bleached grass, frozen earth and snowy white. The blazing fall leaves are gone, replaced with only the skeletal outlines of branches against flat gray skies. There’s less contrast and movement to grab our attention.

Changes are subtle in winter, the movements smaller. But that doesn’t mean they’re not there.

Sensing subtle shifts

A single cattail contains up to 268,000 seeds. I think at least half of them are stuck to my coat. A lazy wind sends the rest floating over the reeds. The ice is thick on Lake Metigoshe, so I’m pondering the novelty of standing in the middle of a marshland as I watch the fuzzy particles lift gently into the air.

The Red River in Fargo is frozen too. But not in the same way. The ice in Lions Conservancy Park is mushy and multi-colored — charcoal dark, snow white, a pale bluish gray that mimics the dusky light. The twists and turns of the oxbows haven’t fully iced over. Tiny whirlpools churn the clay tinted water just visible beneath their slushy edges.

In the nearby river bottom, clusters of polyporaceae mushrooms perch on a decaying log. Thirsty little mosses sip the water from the snow. Wild cucumber pods rustle on the vine. In summer, I wouldn’t notice them. But against this sparse landscape, the fruit’s dried husks are as spiky and conspicuous as a school of blowfish. A lonely bird calls. Life endures.

The word “frozen” indicates stillness. But nature moves. It often happens while we sleep.

Tracks and traces

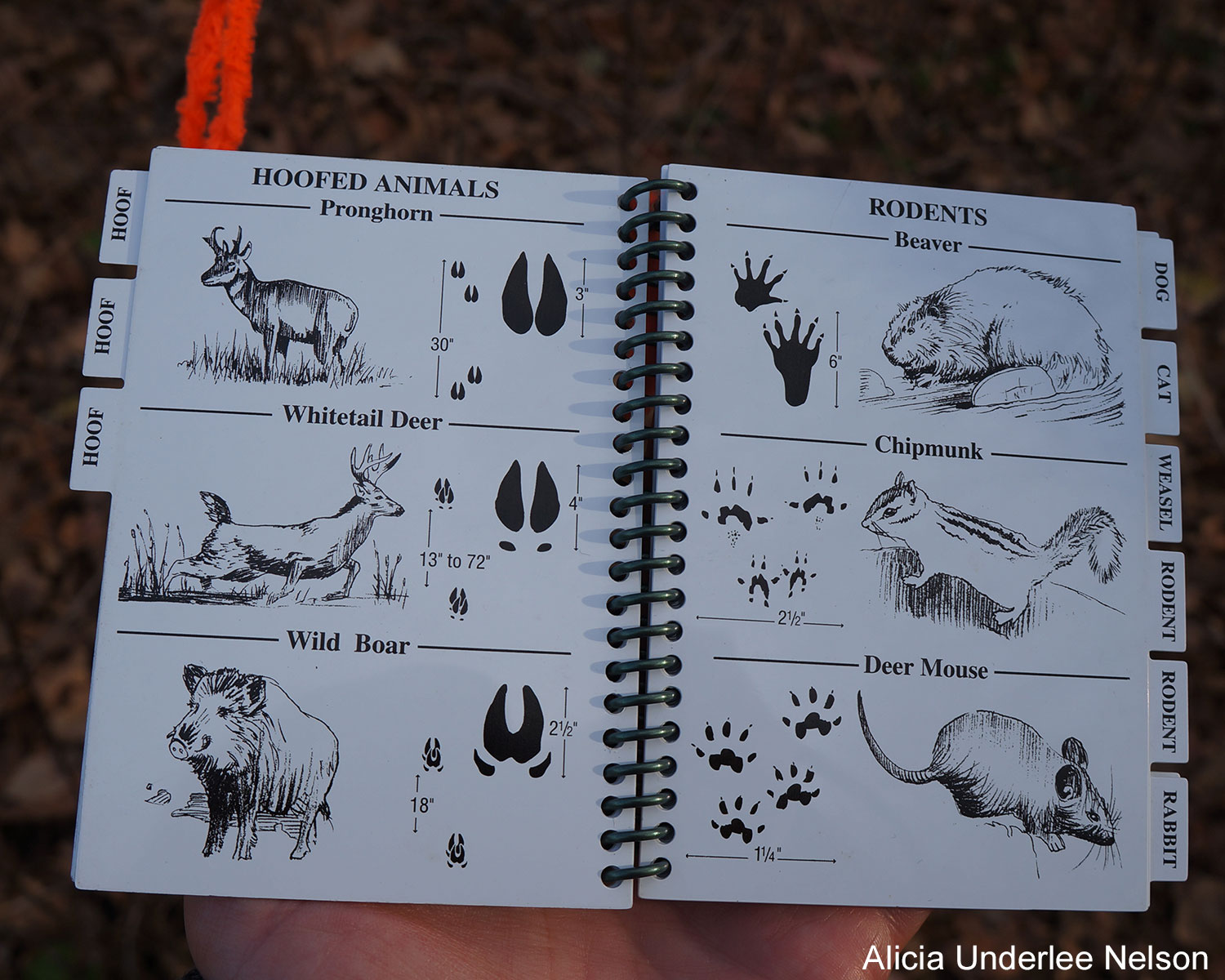

The trails through Lake Metigoshe State Park are covered in a thick blanket of snow. We haven’t seen a single creature, other than the park rangers, but we can tell we’re not alone. Yesterday’s boot prints are crisscrossed by a half dozen tracks.

Identifying the cloven-hoofed deer and bounding rabbit was easy. Squirrel tracks look an awful lot like rabbit tracks in deep snow, until you follow the squirrels’ prints to the base of oak trees.

But there is one set of tracks that has us stumped. They amble along next to my son’s foot prints, each four-toed paw placed neatly inside the imprint of the step before in a perfectly straight line, as if the animal was walking on a balance beam. There were no claw marks, even on the hard-packed snow, so we ruled out a canine. I consulted my field guide (which helpfully included life-sized tracks for comparison) and found a perfect match – bobcat.

The hair on the back of my neck prickled. Suddenly, the ranger’s warning didn’t seem quite so abstract. We walk on, looking up every now and then, just in case.

When in doubt, look up

I’m straddling the border of the U.S. and Canada inside the International Peace Garden (a move that always feels a bit like a party trick) staring at the sky like a child. Feathery cirrus clouds arch across the brilliant blue, their ice crystals suspended like a series of chandeliers. Along the horizon line, dramatically dark stratocumulus clouds churn towards us at a shocking speed, heralding the storm front that will soon bury our log cabin under several inches of snow.

My ancestors, farmers and fishermen, would have been able to read this portent. Thinking of all the things they knew that have been lost to me, I try to capture the day’s clouds in watercolor. They are rosy as cotton candy at daybreak, inky dark and orange when the sun sets over Lake Metigoshe and a dozen combinations of white, black and gray in between.

I turn my face to the sun as it streams through the window, following its warmth and slanting, watery light like a cat. When the moon rises, I follow that too. It’s taken decades for me to finally learn the difference between the waxing and the waning moon, to observe the rhythms that my great-great-grandmothers would have known deep in their bones. But now that I’ve started to notice, I can’t look away.

The power of attention

Tuning in to the moment and noting nature’s subtle rhythms is a skill. Some of us are observant in the way our ancestors would have been forced to be. Naturalists, hunters, park rangers, birders and anglers are good at stillness. They’re accustomed to noticing the tiny changes in their environment. People who pray, meditate, create art or practice yoga often share these skills, although they use them for different purposes. For the rest of us, paying attention takes effort.

“Our attention wanders, relentlessly,” says David George Haskell in “The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature.” “Bring it gently back. Over and over, seek out the sensory details: the particularity of sound, the feel and smell of the place, the visual complexities. This practice is not arduous, but it does take deliberate acts of will.”

At first, I was surprised to read that Haskell, a naturalist and biology professor at Sewanee: The University of the South, used the same language as meditation and yoga teachers. But I shouldn’t have been. Perceiving the natural world and spiritual practices like prayer, meditation and yoga are all rooted in open-minded observation. And Haskell’s groundbreaking book is all about revisiting one tiny patch of ground — exactly one square-meter of old-growth forest — in different seasons. It’s all about noticing the tiny changes from day to day and season to season.

In this spirit, I turned my attention to my own suburban West Fargo neighborhood. For many of us, a daily walk became a pandemic tradition. I just extended mine into the darkest days of winter.

The (sometimes physical) pain of winter

This was easy on warm, sunny days, the kind where snow sparkles on the roof like a Christmas card. But it was much harder on those gray sky days where the cold hits you like a punch to the solar plexus and the air is actively attempting to kill you.

“There is no bad weather, only bad clothing,” is a common expression in Scandinavia. I see this same hardy stoicism in most Midwesterners as we scrape our windshields in the morning and clear the sidewalks after a blizzard.

But while many U.S. residents retreat to the couch to survive winter, most Norwegians live by a philosophy called friluftsliv (pronounced free-loofts-liv), which means “open air living” or “free air life.” It emphasizes staying active outdoors in every season – including the icy northern winters.

Even though daylight is scarce in Norway (Oslo nights drag on for 18 hours in December), many Norwegians soak up this scant sunshine by jogging, skiing, snowshoeing, fat tire biking and exploring their own cities and neighborhoods. Even babies and toddlers get in on the action, napping outdoors in their strollers, bundled up in snowsuits and tucked under layers of thick blankets, tiny little Vikings triumphing over the elements.

I think the Scandinavians are on to something. They reap the physical and mental health benefits of regular exercise and exposure to nature and get a quick hit of Vitamin D from the sunshine while they’re at it. Outdoor activity keeps them moving and breaks up the monotony and depression that can accompany both dark days and limited physical activity. They don’t bemoan or ignore the season -- they celebrate it.

That doesn’t mean they’re in denial about the harshness of winter. It just means that they understand that a fallow period is a necessary part of the life cycle of every living being, including humans.

In “Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times,” Katherine May uses winter as a metaphor for the challenging physical and emotional periods that occur in every human life. Her gentle memoir guides readers to look to nature to learn how to accept and adapt to the hardships of literal and figurative winter.

“We like to imagine that it’s possible for life to be one eternal summer and that we have uniquely failed to achieve that for ourselves. But life’s not like that,” May writes. “It is all very well to survive in the abundant months of the spring and summer, but in winter, we witness the full glory of nature’s flourishing in lean times.

“Plants and animals don’t fight the winter; they don’t pretend it’s not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives that they lived in the summer,” she continues. “They prepare. They adapt. They perform extraordinary acts of metamorphosis to get them through. Winter is a time of withdrawing from the world, maximizing scant resources, carrying out acts of brutal efficiency and vanishing from sight; but that’s where the transformation occurs. Winter is not the death of the life cycle, but its crucible.”

Reimagining familiar ground

These words remind me to be a little kinder to myself about how I’ve weathered nearly two years of a pandemic – an emotional winter none of us could possibly have imagined. These daily walks helped me learn how to flourish in lean times. I took it step by step, moment by moment.

The trees were bare, so the fermenting apple stashed in a tree stood out. A dusting of snow made it simple to follow the squirrel’s route back to my neighbor’s Ohio buckeye. I traced a particularly bold rabbit’s trip up unto my porch steps. (In related news, the mystery of what nibbled last year’s flowers on that same step has now been solved.) And on the very week I learned that mice and voles sleep, eat and move under the snow through a series of subnivean caverns – a sheltered rodent superhighway – I was stunned to see evidence of these very tunnels in my own backyard.

I smelled wood smoke and pine and the boggy wet of decomposing leaves. I spotted last year’s bird nests and watched the seed pods on a row of American lindens quivering in the wind, decorated with a lacy coverlet of frost. I observed the burnished orange maple leaves fading to brown as time, paws and running shoes pressed them into the sidewalks through the month of November. The vivid red sumac and burning bush foliage blazed well into winter, bright as flame against the snowdrifts.

I craned my neck to watch geese fly above the rooftops as I took an unhurried stroll at dusk, just after Thanksgiving dinner. I discovered that the chatty choruses of neighborhood birds prefer blue spruce trees. They hush when I approach, then resume their nattering the second I’m out of sight, like junior high kids when a teacher pokes her head into the classroom.

These kinds of close-to-home observations are common. But they’re not inconsequential. And you certainly don’t need to be an expert to make them. In fact, sometimes an outsider’s perspective is the secret ingredient. Bernd Heinrich’s “Winter World: The Ingenuity of Animal Survival,” tells the story of how the observations of one ordinary person changed how we see the natural world.

Your teacher probably taught you that no two snowflakes are alike. Indeed, every temperature and humidity fluctuation shape every snow crystal into a unique – and utterly ephemeral – creation. But we don’t owe this knowledge to famous scientists like Johannes Kepler (who studied snow’s six-sided structure in the 1600s) or to the generations of academics who built on his research.

Instead, much of what we know about snow comes from the observations of Wilson Bentley, a farm kid from Vermont who took the world’s first photo of a snowflake in his woodshed when he was 20 years old. After studying snow through the lens of his camera and microscope for several years, Wilson went down the road to the University of Vermont and asked if anybody was interested in his photos. By his death in 1931, Wilson had written a book and 50 articles about snow. He also published 2,500 of his 5,000 snowflake images and earned a nickname – “The Snowflake Man.”

As the snow falls softly outside of Dunseith, I’m glad Wilson took the time to explore his particular passion. Because I learned about his life, I now know that the curtain of white blanketing my sleeping car’s windshield is made up of thousands of conglomerate snowflakes, ice crystals that form on warm winter days and combine into large, three-dimensional clusters as they tumble to earth. One sticks to the smooth surface of my glove.

I don’t know what makes me glance down. But when I look, I do a double take. This particular snowflake is a spatial dendrite, an elegant, six-pointed star with graceful arms that mimic the delicate lines of a fern. A tiny column perches at the very tip of all six points, arching upward, a marvel in three dimensions.

I catch my breath and stare. There is again, a rare thing in this cold and weary world.

Winter Reading

- “Forest Therapy: Seasonal Ways to Embrace Nature for a Happier You,” by Sarah Ivens

- “On Looking: Eleven Walks With Expert Eyes,” by Alexandra Horowitz

- “Stokes Nature Guides: A Guide to Nature in Winter (Northeast and North Central North America),” by Donald W. Stokes

- “Stokes Nature Guides: Animal Tracking and Behavior,” by Donald and Lillian Stokes

- “The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature,” by David George Haskell

- “Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times,” by Katherine May

- “Winter World: The Ingenuity of Animal Survival,” by Bernd Heinrich

For Kids (of all ages)

- “Keeping a Nature Journal: Discover a Whole New Way of Seeing the World Around You,” by Clare Walker Leslie and Charles E. Roth

- “Over And Under The Snow,” by Kate Messner

- “Slow Down: 50 Mindful Moments in Nature,” by Rachel Williams

ALICIA UNDERLEE NELSON is a freelance travel writer and photographer from West Fargo. She blogs frequently about travels within North Dakota on her website, prairiestylefile.com.