Nearing an Endpoint

Ron Wilson

From where Jerry Kobriger stands in mid-May on a two-track somewhere in southwestern North Dakota, where cattle graze on one side of the fence and sharp-tailed grouse dance in spring on the other, he can envision an end to something that has been a part of his life for decades.

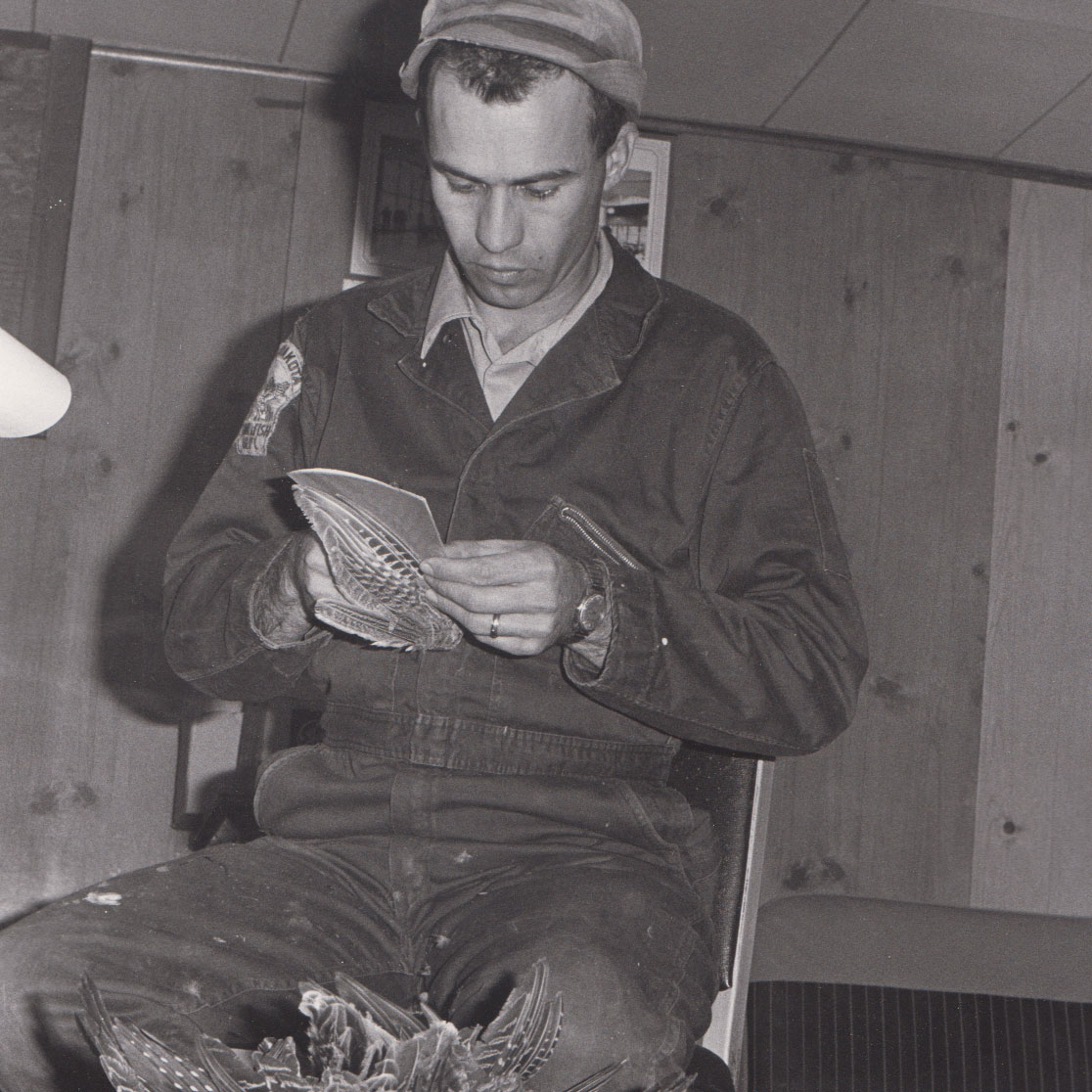

Kobriger, who retired in 2007 from the North Dakota Game and Fish Department as its longtime upland game management supervisor, has been running census surveys and brood counts for 59 years in spring and summer on those birds – sharptails, prairie chickens, pheasants, sage grouse, ruffed grouse – he helped manage for 43 years while with the agency.

Kobriger visited with Jesse Kolar, Department upland game management supervisor in Dickson, about the possibility of notching 60 years.

“Well, I talked to Jesse about that and asked if he’d let me work at least one day next year, then I’ll have 60 years in,” Kobriger said. “And I think that's going to be an endpoint. I don't know what is magic about 60, I mean, it’s just a kind of personal goal, I guess.”

An endpoint to sunrises on the prairie, counting sharptail males as they stomp and coo on some of the same prairie hilltops that attracted generations of birds long before Kobriger started making his rounds in the early 1960s.

“I enjoy going out early in the morning. It’s a nice time to be out here. It’s just a nice job and you don't have somebody looking over your shoulder all the time,” he said. “That’s one of the things that puzzles me. Some people count down almost to the minute when they’ll retire, when they’ll be out of here. And I’ve never felt that way. Nope. Never did.”

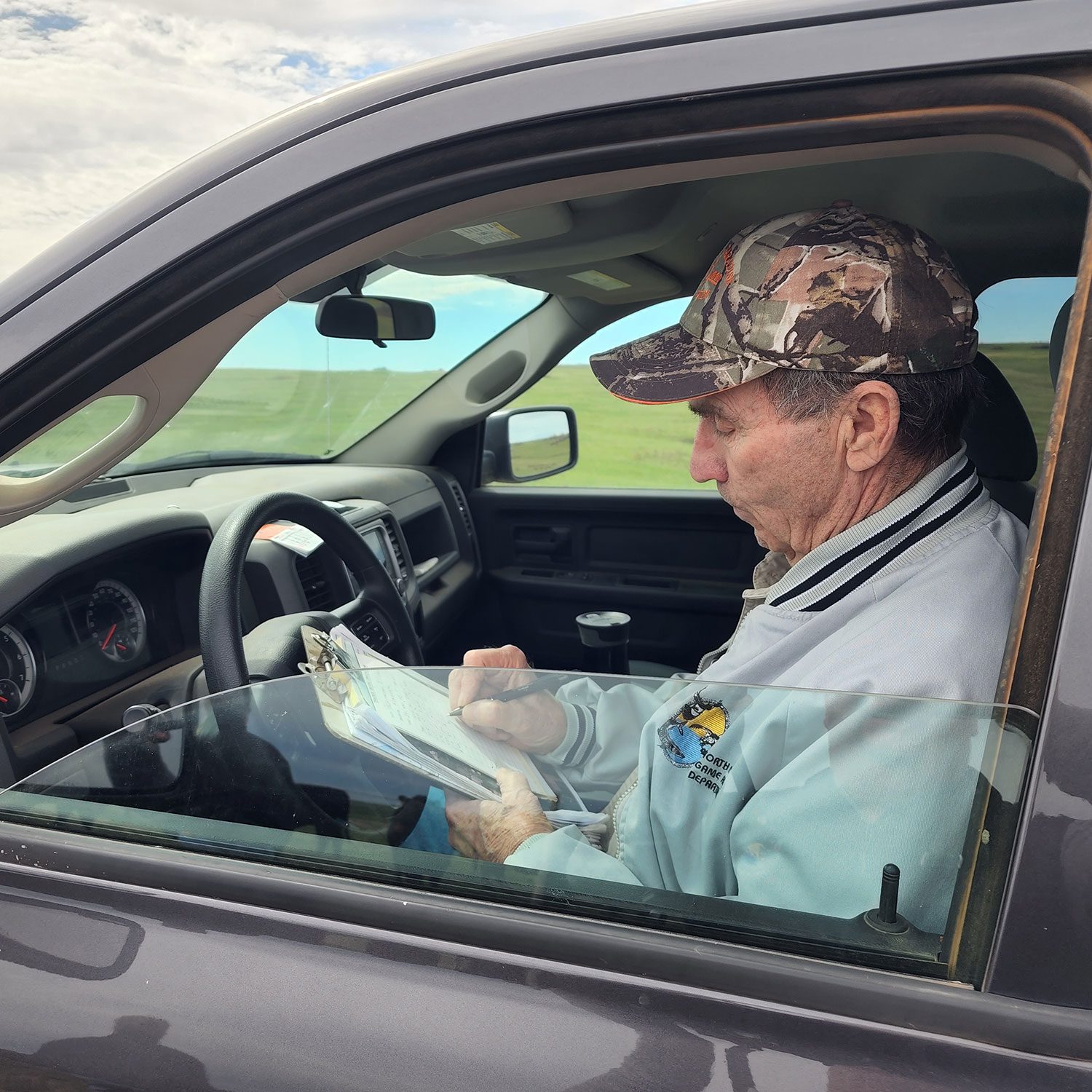

In addition to binoculars, spotting scope mounted on a rifle stock, clipboard and paper to record daily observations and a flat of cookies in the passenger seat, Kobriger carries decades worth of observations, a historical perspective of the land and animals he’s monitored since the early 1960s.

“This is a township that I’ve counted every year since 1964, until Jesse took over the position, and he has done it the last few years now. There are probably 15 to 20 active grounds (leks) on the whole township. Only two of them are on the same spot they were back in the 1950s. All the rest of them have moved around,” he said. “Some of them moved two or three times. I don’t know why the grouse move. Sometimes they’ll move from a nice grassy area like this, to a stubble field or something. And why do they do that? That’s not what the literature says they do, but it’s up to the birds. They go where they want to go.”

In his nearly 60 years of slowly prowling North Dakota’s landscape, looking for pheasant broods in roadside ditches or sharptails gathering on leks, Kobriger couldn’t help but notice changes to the landscape, no matter how subtle.

“The one thing in the Badlands, of course, is the oil development. When I started, I was going to a meeting with the Forest Service and I was riding with the district ranger, and I said, ‘How long do you think this oil field is going to last?’ and he said, ‘Well, they’re predicting about 20 years.’ That was in 1964. So, you can see the change. And that's something that everybody notices because it’s so evident,” he said. “There’s a lot of other subtle changes that go on that you don't really pick up on right away. It’s like if you look in the mirror in the morning and tomorrow morning, there is no change. But if you had a back button on that mirror like you do on a computer, you could go back, back, back to day one. Who is that guy? I mean, there's a lot of land use changes that you just don’t notice.”

Determining the highs and lows of doing survey work for nearly six decades is a difficult question, but one that Kobriger answered after a pause.

“A couple of highlights, I guess, would be finding a new dancing ground, particularly if there hasn't been one in the area before or when you’re running brood surveys and finding sharptail broods,” he said. “I guess the one thing that kind of bothers me is that the partridge population really dropped. One year, hunters harvested almost a quarter million partridge, and in 1992 they took a big drop and just never recovered. And I don’t know why, and I don’t think anybody else knows why. I mean, they have some ups and downs, but nothing like they were back before that big drop.”

After a 43-year career with the Game and Fish Department, and his continued work with the agency after retirement, Kobriger has some advice for those younger people thinking about a conservation career.

“Let me tell you a little story about that. I went to a meeting of the Central Mountains and Plains Wildlife Society, and I think it was in Colorado. And I gave a report on the land use study that we did down at Bucyrus. I showed all of the land measurements and stuff that we did,” he said. “When I got to the question-and-answer part of it, a guy raised his hand and said, ‘You know, I really enjoyed that because it actually showed somebody out in the field doing something.’ I mean, some people, if they can't do it on the computer, they just won’t do it, it seems like, or they don’t do it as much as they should. My point is, don’t lose contact with the outdoors and with the field.”

Kobriger hasn’t for nearly 60 years.

Kobriger records data from his morning observing sharp-tailed grouse.

A younger Jerry Kobriger checks upland game bird wings back in the day while with the Game and Fish Department.