A Break From Mothering

Ron Wilson

Sometimes bighorn sheep gotta take a break.

While adult rams and ewes counted during the North Dakota Game and Fish Department’s last survey were near record numbers, lambs recruited into the population declined 21% compared to the year before.

After two-plus decades of studying bighorn sheep in western North Dakota on some of the state’s ruggedest terrain, Brett Wiedmann, Department big game management biologist, isn’t losing any sleep over the dip in lamb recruitment.

You could argue that predation and drought maybe played roles in the lamb decline, but based on his years of experience, Wiedmann believes some ewes simply took a year off from mothering.

“I noticed this by observing bighorns that, let’s say, you have a group of 15 ewes, and they’ll have three years of recruiting a lot of lambs. Then on year four, I’ll count them, and zero, no lambs,” he said. “So, the immediate reaction is disease. Do they have disease in the population where these lambs have died of pneumonia? But then the following year lambs are back. Because the ewes invest a lot of energy into recruiting lambs, nursing those lambs, being dedicated to their young, some years a decline in lambs can just be attributed to taking the year off, putting on body weight, feeding rather than raising another lamb.”

A healthy ewe is key to raising a healthy and hardy lamb that needs to be up to the task of navigating the difficulties of the badlands almost immediately.

“Bighorn sheep are completely unique compared to deer, elk and moose in that when a bighorn ewe gives birth, that lamb needs to be up following its mother at heel within about four days,” Wiedmann said. “Bighorns do not hide their young like deer where they hide in the grass, and then the female wanders off. Bighorn lambs join nursery groups of adults at about 4- to 7-days-old. They’re tiny, about 10-11 pounds. So, they’re exposed to predators right away. And that’s why, again, the bigger, the more athletic, the stronger the lamb, the higher its odds of survival.”

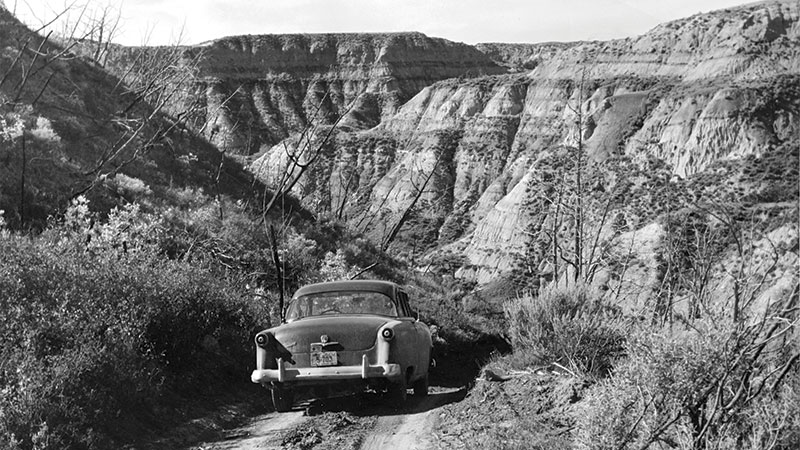

Since the reintroduction of bighorn sheep in the badlands by the Game and Fish Department nearly 70 years ago, and certainly since the last native bighorn was killed at Magpie Creek in 1905, these animals are doing way better than OK today.

Even so, while bighorns are at record numbers and continuing to grow, there have been some hurdles along the way, namely a pneumonia outbreak in 2014 that killed 15-20% of the population and still lingers in some populations today.

The oldest ewe, also collared as a yearling so there was no mistaking her age, was 22.5 years old.

“If a hunter harvests a 5-year-old mule deer buck or a whitetail buck, that’s going to be a tremendous buck,” Wiedmann said. “A 5-year-old ram is a teenager. He’s just entering maturity. The prime for a bighorn ram is really 8 to 10 years old, making them much longer-lived than deer.”

Two-plus decades ago when Wiedmann was hired, there was little known and so much to learn about the bighorns living in the badlands. Biologists didn’t know where the bighorn sheep were hanging out. They didn’t know their recruitment or survival rates. They didn’t know home ranges. With the advancement in technology and a lot of hiking the rugged badland’s terrain, there’s little for the bighorn sheep to hide from biologists today while observing from a safe distance.

“A big challenge was just identifying where we had bighorn sheep. We now have GPS collars on every single subgroup of bighorn sheep in the badlands. So basically, when I do my survey, at 6 a.m. I get all those locations on my phone,” he said. “Now, our counts are very accurate. We are capable of locating and counting every single, little subgroup of bighorn sheep in the badlands.”

Out of Harms Way

Construction of a wildlife crossing completed in summer 2021 to safely usher bighorn sheep and other big game animals from one side of U.S. Highway 85 to the other in western North Dakota is working maybe better than expected.

In fall 2021, Game and Fish Department trail cameras photographed bighorns for the first time using the underpass located just south of the Long X bridge near the North Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

Once the project was completed, it was only a guess on how well it would work, said Brett Wiedmann, Department big game management biologist, because bighorn sheep are hesitant to enter tunnels where they naturally fear being ambushed by predators.

“We were a little bit nervous that they wouldn’t want to go into the crossing. But it far exceeded our expectations. We’ve had hundreds of crossings of bighorn sheep through the underpass and thousands of mule deer crossing as well,” he said. “We have not had a single bighorn sheep killed on that stretch of highway since the project was completed. Not only has it saved a lot of mule deer, a lot of bighorn sheep, but it’s also a safety factor for the public where we’ve prevented a lot of collisions coming down a real steep hill. It has just worked phenomenally well.”

Wiedmann said the Long X herd is the second largest population of bighorns in badlands.

“There’s currently 75 bighorn sheep in the herd,” he said. “When you take away all those mortalities due to vehicle strikes … they’re really taking off now.”