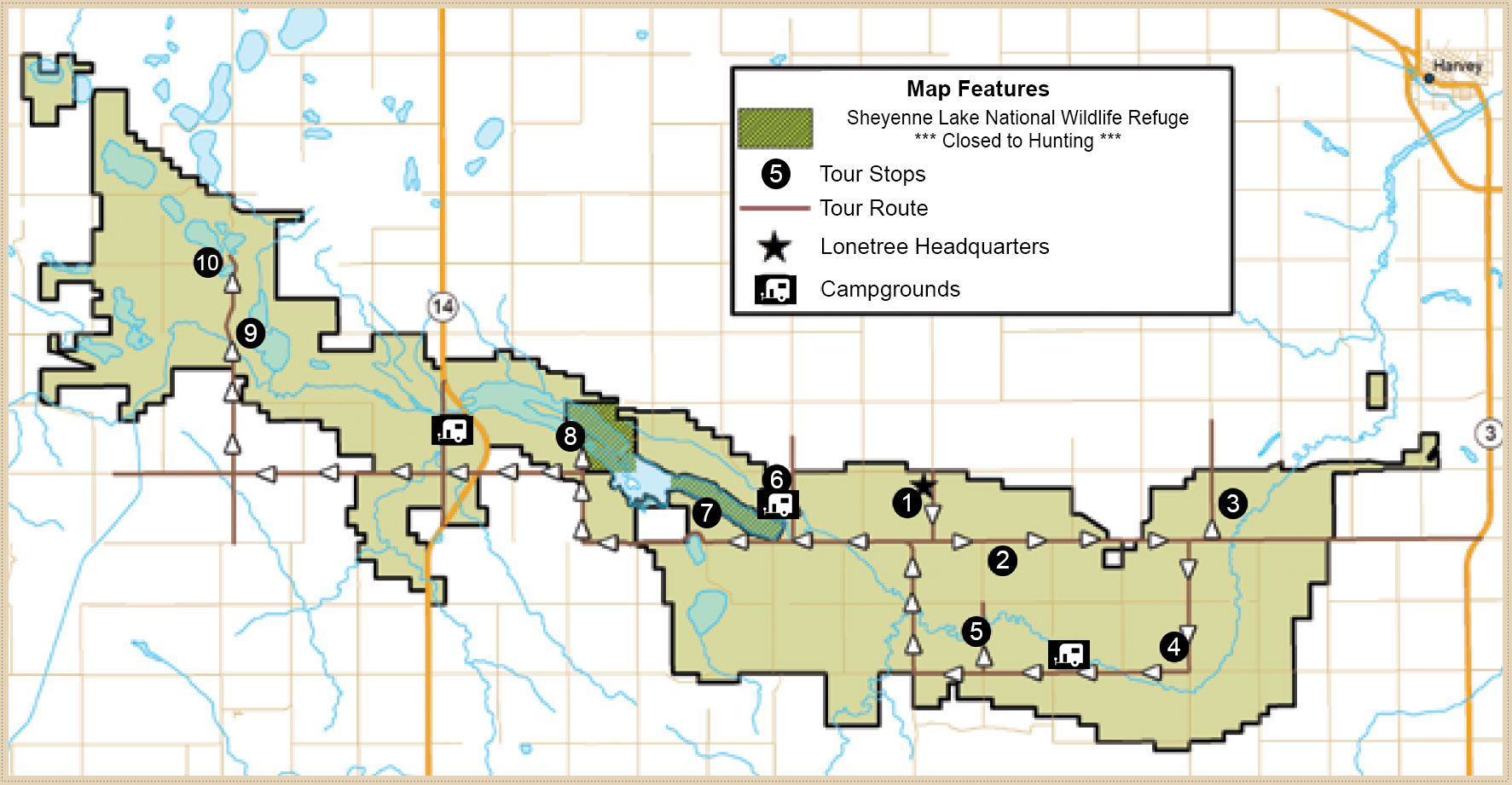

Lonetree WMA Driving Tour Stops

The following is the online version of the Lonetree WMA Driving Tour brochure. Descriptions of each stop on the tour can be viewed below.

Note: Motorized vehicles must stay on established roads and trails.

Lonetree Wildlife Management Area represents a unique wildlife management and recreational opportunity for North Dakotans. Its nearly 33,000 acres were originally purchased by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for use as a regulatory reservoir, part of the Garrison Diversion Irrigation Project.

In 1986, Congress reformulated the project and recognized that there was no immediate need for the reservoir.

In the interim, Congress directed the Bureau of Reclamation to develop the area for wildlife, under the management of the state of North Dakota.

Management on Lonetree today has two main goals.

The first is to develop the site as wildlife habitat, and the second is to make it accessible for the widest range of public use.

Stops along the driving tour will point out some of the activities at Lonetree designed to enhance its value for wildlife.

Visitors are encouraged to make the fullest use of the area.

- Campsites, parking lots, hiking trails and observation blinds are available for public use.

- The driving tour is just over 32 miles long; allow yourself at least two hours to visit all the sites.

- Visitors can cut the tour approximately in half at site number 6.

- All the sites are on Lonetree, but access is via public roadway.

- Watch for traffic and signs designating the boundaries of Lonetree WMA.

- Be respectful of private land.

Driving Tour Stops

Stop 1: Grass Plantings, Wildflower Plantings and Dense Nesting Cover

Along the road opposite Lonetree headquarters are some typical wildlife habitat restoration efforts.

Once mostly cropland, Lonetree now features native grasses, forbs and dense nesting cover for upland nesting birds like ducks and sharp-tailed grouse.

Native grasses are resistant to drought, control erosion and improve soil health.

Dense nesting cover – mostly clover, grass and alfalfa – hides nests and newly hatched broods from predators.

Wildflower/forb seed mixed with grass seed gives a sprinkle of color and a wider diversity of plant and insect life.

Typical grasses on Lonetree include Western wheatgrass, green needle grass, blue grama, side oats grama, big bluestem and little bluestem.

A typical wildflower is the purple coneflower, which was important to native people as a medicinal plant.

Stop 2: Tree Planting

The tree planting you see was planted to provide permanent winter cover for wildlife on Lonetree.

Approximately 300 acres of trees were planted each spring to arrive at the current tree cover, which is about 2,100 acres.

Tree and shrub species in this and other plantings include chokecherry, buffaloberry, green ash, spruce, cottonwood, rose and snowberry.

Tree plantings are carefully designed so the shape slows winter winds to create snow-free areas.

The snow-free areas are planted to fruit-bearing species like buffaloberry and chokecherry to provide winter food.

The winter cover provided by tree plantings is of value to white-tailed deer, moose and pheasants.

Stop 3: Demonstration Plot

This demonstration plot represents various species of grasses and forbs that were found historically in native prairie.

Due to changes in land use, these species have declined in abundance.

Although this plot is an attempt to recreate what once was naturally occurring, it is difficult to duplicate the diversity of true native prairie.

It is also expensive, as seed costs for native species are much higher than those of tame grasses.

But native species of wildlife and native prairie evolved together.

Native plants form cover that is the right height and density for native birds and has provided for their needs without our help for centuries.

Native plants evolved in this climate and are drought resistant and winter hardy.

In the long run, native prairie will assure healthy populations of native species like sharp-tailed grouse.

A major goal on Lonetree is to increase the abundance of this type of habitat and maintain it through fire and grazing, two historically important events that were common and familiar to native species.

Fire and grazing have many benefits, with diversity in species and structure being two of the most important.

Stop 4: Restored Wetland

The low-lying area on the north side of the road was once a wetland that was drained for use as cropland.

The drain is plugged, allowing water once again to pond.

As this occurs and typical wetland vegetation recovers, the site will once again provide for the needs of nesting and brood rearing wetland wildlife.

Open water in wetland areas like this one provide food for breeding and nesting birds.

Later in summer, it will provide safety for waterfowl broods until they are able to fly.

The uplands provide dense nesting cover and shelter for young birds after they hatch.

Concrete culverts placed on end and large flax bales provide nesting sites for geese, which prefer to nest where open water provides good visibility and safety from predators.

Stop 5: Historic Winter House

The Winter house, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was built around 1900 by Daniel Winter, a Russian German settler.

A number of members of the Winter family settled near here and built similar houses, and this was one of the last ones to exist until it became unsafe and was ordered to be taken down.

The house was built in a style which was typical in Russia and the Ukraine.

It was an architectural method particularly well-suited to treeless, semi-arid plains.

The house was made of “puddled clay,” a mixture of clay and straw, which was molded or poured in place in layers 18 inches high.

The 2-foot-thick walls could be built with little need for scarce lumber, and provided effective insulation against both heat and cold.

Although small by today’s standards – the dwelling was only two rooms and measured 18 feet by 26 feet – it was an efficient building, needing little fuel to heat it in winter.

Stop 6: Food Plots

One of the most important management techniques used on Lonetree and other WMAs in North Dakota is the planting of food plots.

Food plots are simply crops planted and left standing through winter to provide food for wildlife.

Different wildlife species have different needs.

The food plots here are primarily corn and sunflowers, however, about 25-35 percent are other small grains or cover crops (for soil health).

The standing stalks provide cover for feeding, and provide some cover from weather, especially during harsh winters.

Food plots on Lonetree also help in keeping wildlife from doing damage to crops and domestic livestock feed supplies in neighboring areas.

Food plots are usually strategically located next to permanent winter cover like tree plantings or cattail marshes.

Stop 7: Sharp-tailed Grouse Dancing Ground

Every spring, the high knoll in front of visitors becomes a dancing ground for male sharp-tailed grouse.

Even though all of North Dakota’s prairie grouse perform a similar mating ritual, only sharptails are said to “dance.” Sage grouse “strut” and prairie chickens “boom.” All of these courtship grounds, whether dancing, booming, or strutting, are called “leks.” (In the event this lek is/or becomes inactive, visit the Lonetree office to see where a better spot may be for viewing or utilize a viewing blind, which is explained below.)

The time to watch the grouse dance is at sunrise early in spring.

Although no viewing blind is placed at this lek, it is possible to watch the annual mating ritual from the road with binoculars or a spotting scope.

It’s best to stay in your vehicle to avoid alarming the birds.

If the birds flush, stay awhile as they might return.

At least one viewing blind is placed at another lek on or next to Lonetree WMA.

See the WMA manager for its current location and to make a reservation for use.

Stop 8: Sheyenne Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Lonetree is the only WMA with a national wildlife refuge within its boundaries.

National wildlife refuges are located throughout the country primarily to protect and manage migrating waterfowl.

Sheyenne Lake NWR is an easement refuge.

The U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service controls hunting activities on this refuge where more restrictions are in place, particularly during waterfowl season, when no hunting is allowed.

Although the refuge is managed primarily for waterfowl, it is a valuable area for other wildlife.

One of the management tools visitors might see here is an electric predator fence on the peninsula, about 200 yards off to the left.

This fence is sometimes used to restrict nest predation by raccoons, skunks, mink and foxes.

Stop 9: Native Prairie

The area across the road to the east is a parcel of native prairie.

This means that this piece of land has never been converted to cropland.

Tracts of native prairie are not as common as they once were, making the remaining parcels much precious.

Historically, these grasslands were kept vigorous with periodic grazing by bison and naturally occurring wildfires.

The small knolls to the east, which overlook the Sheyenne River, are home to a number of Native American tipi rings.

These rings consist of several field stones arranged in a circle.

They are not easily distinguished, but a careful observer may pick them out of the prairie.

Stop 10: Saline Lake Plover Site

Saline wetlands, like the one in front of you, are particularly important nesting places for shore birds, especially piping plovers.