Chronic wasting disease takes its time and the outcome is always the same.

Once a deer, elk or moose is infected with the disease, it can take on average 18 months or longer before the animal rapidly loses body condition, starts to act strange, becomes emaciated and dies.

Hunters remain the best and most important tool in slowing the spread of CWD in North Dakota.

“It’s important to remember that for the most of that period of time that infected deer will look perfectly healthy, feed with other deer and travel across the landscape as a normal deer would,” said Dr. Charlie Bahnson, North Dakota Game and Fish Department wildlife veterinarian. “The fact that you have this seemingly healthy deer on its way to death is what makes this disease particularly challenging to manage.”

The first month or two after a deer is infected is likely the only time it’s not a threat to other animals.

“Studies have shown the disease agent in the saliva, urine and feces starts a couple months after infection,” Bahnson said. ‘So, for several months thereafter, it’s a danger to the rest of the herd, potentially infecting them.”

Bahnson said CWD was first recognized in Colorado in the 1960s in captive research facilities, and then in wild deer in the area in the 1980s.

It was long a concern, yet remained somewhat of a curiosity in North Dakota, until the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“But at that point, it started showing up in other states and Canada, and we started looking for it intensely in North Dakota,” Bahnson said.

By the early 2000s, CWD had been found in farmed and wild animals in parts of Wisconsin, Montana, Minnesota, South Dakota and elsewhere.

At the time, the North Dakota Game and Fish Department and other state agencies intensified efforts to test farmed and wild animals for the disease – 470 deer and 25 elk shot by hunters in 2002 tested negative – in the state, while holding collective breaths for the first positive result.

“We’re not just in this for a few years … We are concerned about the overall health of North Dakota’s wildlife,” said Jacquie Gerads, former Game and Fish Department wildlife disease biologist in 2003. “Is it only a matter of time? If so, I can’t tell you what that time frame is.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t take that terribly long.

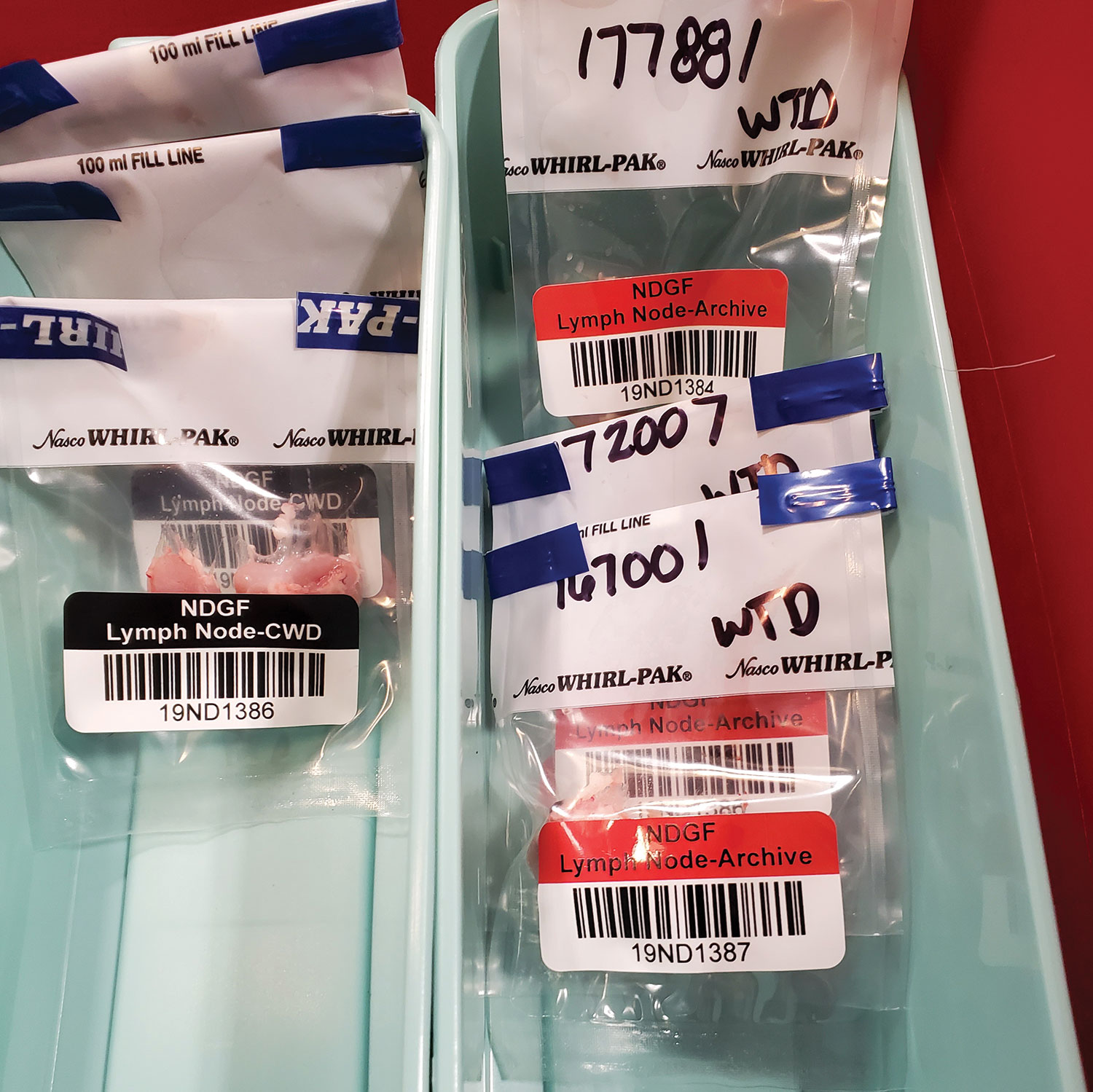

In 2019, the Game and Fish Department collected about 3,500 samples for chronic wasting disease testing from hunter-harvested animals. Efforts to further test deer, elk and moose are ongoing.

“We first started finding deer with CWD in Grant and Sioux counties, hunting unit 3F2, in 2009, and we’ve been finding positive deer down there ever since,” Bahnson said. “And in 2018 we found it for the first time in Divide County, unit 3A1. And since then, we found it farther south as well in Williams County in unit 3B1 and then unit 4B last year.”

Fortunately, and this is important to remember, while a number of deer have tested positive for the disease in North Dakota, the prevalence of CWD remains low, from 2-5%.

“An important thing to emphasize is that we certainly care about where CWD is, but probably equally important is how common it is within our hunting units,” Bahnson said. “CWD remains at a low prevalence and it’s probably not terribly important in terms of having long-term population level impacts. But once it starts to climb, you get into this exponential phase where the prevalence will start to rapidly increase and you’ll start to pass this threshold where all of a sudden it’ll have a really meaningful impact on your population.”

It’s hard enough a being deer in North Dakota, Bahnson said, when you factor in the hard winters, predators, fragmented landscape and other diseases that occasionally come through a herd. If you add substantial mortality due to CWD year after year on top of all that, it’s difficult to see how that population can remain viable long term.

“Right now, one of the positive things is that we still are fairly early in the course of the disease in North Dakota. Much of the state remains disease free, and where we have it, the prevalence is fairly low,” he said. “Comparably, there are other jurisdictions, both Canadian and the United States, where they’ll have a local prevalence of 30%, 40%, 50%, if not higher. And once you reach that point, your options are pretty limited. I use those examples as a word of caution and say that we need to do everything we can right now to keep things in check in North Dakota.”

The best tool to do so, Bahnson said, is sufficient, appropriate hunter harvest season after season, which is what wildlife managers have long thought and continues to be born out in scientific literature.

“Hunters are absolutely our best and most important tool,” he said. “If you manage a healthy, sustainable population at the right deer densities, we reduce how many contacts that are occurring on the landscape. But importantly, we are also getting positive animals off the landscape every year.”

An infected deer sheds the disease through its bodily fluids – urine, saliva and feces. Understanding this, when it comes in contact with other deer, it can infect those animals as well.

“But also, those bodily fluids remain infectious on the landscape for years afterwards, so that is a source of infection as well,” Bahnson said. “And we also know that its carcass parts, particularly its nervous tissue, the spinal column and the brain are a source of infection long after the animal dies and the carcass breaks down.”

Understanding how CWD is transmitted and continues in the environment is key to how wildlife managers in North Dakota and elsewhere are addressing it.

“A hunter can be well intentioned, but harvest an animal that looks perfectly healthy, travel a great distance, butcher the animal,” Bahnson said, “but if those high risk parts end up on the landscape, that can be a source of infection. That’s why we have transportation restrictions in place.”

Knowing that CWD is transmissible and can be spread from animal to animal, or indirectly through contaminated environments, the Game and Fish Department has restricted baiting in hunting units where CWD has been detected or are at risk of having CWD show up in the near term.

“There are infected deer out on the landscape right now that are a major threat when they come into contact with others. We know that baiting brings a lot of unrelated individuals into close contact, but we also know that an animal eating feed off a common pile on the ground where a lot of other animals have been is likely to eat feed that has been contaminated by bodily fluids,” Bahnson said. “Restricting baiting is a way that we as hunters can reduce the overall risk of the disease spreading.”

There are a lot of strong opinions about baiting, Bahnson said, and some people have a hard time accepting the restrictions.

“But it’s undeniable that baiting is a thing that we have the ability to stop doing in order to reduce the overall risk,” he said. “We don’t pretend to say that it’s going to stop all deer from congregating. We absolutely know that deer congregate in certain times of the year. We know that they are social animals. That being said, it is a way that we can reduce the overall number of those high-risk contacts.”

Testing in North Dakota for the invariably fatal disease began in 1998 with roadkilled, sick and suspect animals. In the early 2000s, Game and Fish increased CWD surveillance efforts by annually collecting samples from hunter-harvested deer, elk and moose.

The Department has collected thousands of samples from (mostly) deer, elk and moose over the years. Typically, surveillance efforts from hunter-harvested deer focuses on a third of the state on a rotating basis, and those areas where wildlife managers are trying to manage for CWD.

Last year, the Game and Fish Department collected about 3,500 samples from hunter-harvested animals. And like most years, 300-400 of those samples were from each hunting unit where CWD has been confirmed.

Given the unusual circumstances with the COVID situation, the Game and Fish Department will focus its hunter-harvested surveillance efforts this fall in areas of the state where CWD has already been detected.

“This year, given the COVID situation, we’re prioritizing with our hunter-harvested surveillance in the northwestern and southwestern parts of the state,” Bahnson said. “We had initially planned to do the central third of the state, but we’re going to put that on hold until next year so we can focus our resources, our personnel, on areas where it’s a little greater concern.”

While surveillance is an essential part of managing for CWD, Bahnson said it’s important to note that testing deer doesn’t actually address the disease on the landscape but helps wildlife managers understand what is going on so they can tailor their management.

“We really rely heavily on hunters to submit heads for sampling, we rely heavily on taxidermists, meat lockers and gas stations that are willing to host the drop-off sites,” he said. “In terms of compliance from hunters, it varies quite a bit. In units where we have CWD documented, roughly 10% of license holders end up dropping off heads for sampling. Outside those units, in adjacent units, we’re looking at more like 2% to 3%. So, that’s a number we’d like to see increased quite a bit.”

In hunting units where CWD is documented, it’s important to get a good handle on how common it is. But equally important, Bahnson said, is documenting where CWD is not.

“In order to be confident in saying that we don’t have CWD in a unit, we have to test a lot of heads. Only testing 10 heads doesn’t give you much confidence,” he said. “But if we can get a lot of hunters to participate, if we can test a few hundred heads from each unit, then we can start to confidently make assessments of whether CWD is likely there or not. So, hunter surveillance is a critical part of the big picture.”

CWD presents a lot of challenges for wildlife managers – especially when you consider deer move naturally, unimpeded, across the landscape – and it’s probably fair to say that the disease will likely show up in other areas of North Dakota given time.

“But I think it’s important to realize that when that happens, that’s not the end of the fight … I don’t look at that as a reason to say it’s hopeless,” Bahnson said. “I say that when it shows up in an area, that means it’s time to take the next steps to keep things in check.

“Because, again, we can live with CWD at low infection rates, probably indefinitely,” he added. “If we say it’s a hopeless endeavor, if we give up and let those infection rates blow out of control, then it truly will be a hopeless situation.”

Transporting Big Game

Big game hunters are reminded of requirements for transporting deer, elk and moose carcasses and carcass parts into and within North Dakota, as a precaution against the possible spread of chronic wasting disease.

Hunters are prohibited from transporting into or within North Dakota the whole carcass of deer, elk, moose or other members of the cervid family from states and provinces with documented occurrences of CWD in wild populations, or in captive cervids.

In addition, hunters harvesting a white-tailed deer or mule deer from deer hunting units 3A1, 3B1, 3F2, 4B and 4C, a moose from moose hunting units M10 and M11, or an elk from elk hunting units E2 and E6, cannot transport the whole carcass outside the unit. However, hunters can transport the whole carcass between adjoining CWD carcass restricted units.

North Dakota Game and Fish Department district game wardens will be enforcing all CWD transportation laws.

Hunters are encouraged to plan accordingly and be prepared to quarter a carcass, cape out an animal, or clean a skull in the field, or find a taxidermist or meat locker within the unit or state who can assist.

Game and Fish maintains several freezers throughout the region for submitting heads for CWD testing.

For questions about how to comply with this regulation, hunters should contact a district game warden or other department staff ahead of the planned hunt.

The following lower-risk portions of the carcass can be transported:

- Meat that has been boned out.

- Quarters or other portions of meat with no part of the spinal column or head attached.

- Meat that is cut and wrapped either commercially or privately.

- Hides with no heads attached.

- Skull plates with antlers attached with no hide or brain tissue present.

- Intact skulls with the hide, eyes, lower jaw and associated soft tissue removed, and no visible brain or spinal cord tissue present.

- Antlers with no meat or tissue attached.

- Upper canine teeth, also known as buglers, whistlers or ivories.

- Finished taxidermy heads.

Hunter-harvested Surveillance

Surveillance efforts during the 2020 hunting season will focus on areas where CWD has been previously detected. If you harvest an animal from one of these areas, drop off the tagged head at one of the collection sites.

Every effort will be made to provide results within 3 weeks. However, delays may occur due to COVID-associated challenges.

Results from lottery licenses (gun, youth, moose, muzzleloader, elk) can be accessed through your Game and Fish account.

For nonlottery licenses (archery), results will be provided via email or text message, based on your preferred communication method as listed on your Game and Fish account.