Upland Game Identification Guide

To an individual hunter, whether a sharptail is a male or female, or whether a pheasant rooster is a juvenile or adult, is little more than simple curiosity. This guide is designed to satisfy that curiosity – to show indicators biologists use to determine sex and/or age of upland game birds.

When you know what to look for, you can usually make a pretty good guess as to the sex and/or age of the birds in your bag (even biologists are occasionally stumped). If nothing else, you can impress your hunting partners with your new-found knowledge.

Some Basics

This guide covers five species of nonmigratory game birds in North Dakota – ring-necked pheasant, sharp-tailed grouse, gray partridge, ruffed grouse and wild turkeys.

For all species except pheasant, the key to age is hidden in the wing, specifically the outer three large feathers called primaries. For identification purposes, these feathers are numbered. The outermost primary is number 10, the next one in is nine, the third one is eight, and so on. Each species has 10 primary feathers.

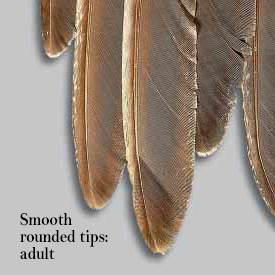

Adults of all upland species as well as fully-molted juvenile pheasants, exhibit the same characteristics – rounded feather tips and smooth edges on the outer three primaries.

Another good general rule for determining age is to look at the underside of the number nine and 10 primaries. Pull back some of the small covert feathers so you can see the “quill” part of the primary feather. If the quill part is blue and soft, that indicates the feather is still growing, and the bird is an adult. On the other hand, if the number eight and/or seven primaries are still growing, then the bird is likely a juvenile.

When wing primaries are fully grown, the quill part becomes hard and white or light gray, then you have to look at the wear and contour between eight and nine and 10.

To check wear of the outer primaries, look at the top side of the wing. If the ends of the outer two feathers are somewhat rounded and smooth, the bird is likely an adult. If ends are more pointed and frayed, the bird is likely a juvenile.

This photo shows the underside of a sage grouse wing. You can judge this bird as an adult, because the ninth and 10th primaries are still growing, as evidenced by the bluish "quill" section. If the eighth or seventh primaries look like the feathers in this photo, and the ninth and 10th primaries are not growing, the bird is a juvenile. These characteristics apply to all upland species except pheasant. Later in the season, when all feathers are completely grown, the "quill" part of the outer primaries will be white and hard. When this occurs, gauging the appearance of the outer three primaries will tell you if the bird is a juvenile or adult.

This rule applies to all birds covered here, except pheasants. Whether a rooster pheasant is an adult or juvenile is determined by the length and appearance of the spur between the foot and knee.

Sex determination is different for each species. For pheasants, the difference is obvious. For sharptails, key indicators are coloration of the central two tail feathers, and the feathers on the top of the head. For Huns, it’s feather coloration on the shoulder of the wing, and for turkey it’s the breast feather color pattern. The sex of a ruffed grouse is best determined by dot patterns on rump feathers.

This basic guide contains text and photos that will help you learn more about the birds you bagged. If you use it enough, you may reach a point where you no longer need it.

For all our upland game species except pheasants, the key to determining whether the bird is an adult or young-of-the-year is the appearance of the outer three primary wing feathers. The outermost large wing feather is numbered 10. The next one in is number nine, the next one is eight, and so on. While this is a sharptail wing, feather numbers are the same for all species.

The outer three primaries shown here are attached to the wing of a juvenile sage grouse. Note the pointedness and frayed edges on the eighth and ninth primaries. These characteristics are the same for juveniles of all upland species except pheasants. Also note the specks and more mottled coloring of the juvenile wing, compared to the adult.

This photo shows the outer three primaries of an adult sage grouse wing. Note the rounded tips and smooth edges. Adults of all upland species as well as fully-molted juvenile pheasants, exhibit the same characteristics – rounded feather tips and smooth edges.

Rooster Pheasant

A hunter needs to know the difference between a hen and rooster pheasant before he or she pulls the trigger. Most of the time, the identity of the flushing bird is obvious.

There are situations, though, when it is good to hesitate or hold back. Birds flushing into a rising or setting sun are often a tough call.

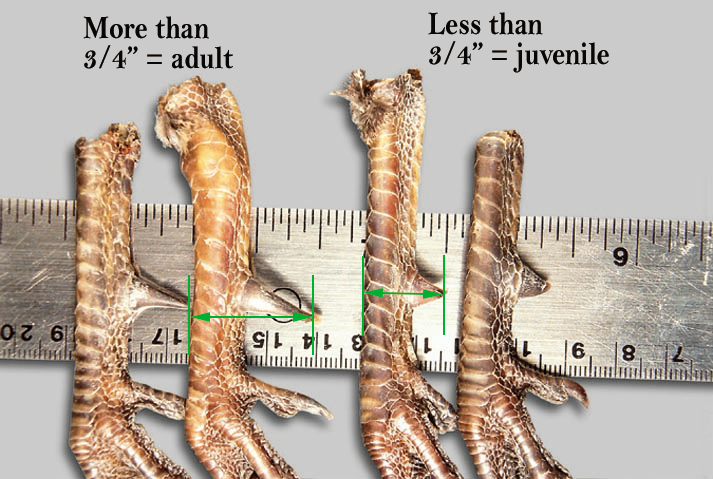

In addition, early in the pheasant season, juvenile roosters can be fully-colored or hardly colored at all. The key to determining age between fully-colored juvenile roosters, and adult roosters, is the spur located on each pheasant leg between the foot and knee.

All rooster pheasants have spurs, while hens don’t. That’s why a foot left on a dressed pheasant is adequate for determining sex.

Spur length can vary from just a small nub on a very young bird, to more than 3/4 of an inch, including leg bone, on adult birds. The general rule for determining a rooster’s age is if the spur is less than a 3/4-inch in length, including the leg bone, the bird is young-of-the-year. If the spur is more than 3/4-inch long, including the leg bone, the bird is an adult.

If there is any doubt as to age based on spur length, spur appearance is the deciding factor. If the spur is dull-colored, and the point is blunt and soft, the bird is a juvenile. If the spur is black, shiny and sharply pointed, the bird is an adult.

In a normal fall, even without looking at the spur, a hunter has roughly an 80 percent chance of guessing whether a rooster in the bag is young-of-the-year or an adult. In an average year about 80 percent of the pheasant bag is juvenile birds. Early in the season, the ratio of juvenile to adult birds is even higher, up to 90 percent. Later in the season, harvest might include only 70 percent juveniles.

Biologists do not use pheasant wings to determine whether a bird is a juvenile or adult. Both juvenile and adult pheasants molt all their primary wing feathers each year, so the appearance or growth stages of the primaries is not used to separate young and adult birds. However, pheasant hunters do send in wings along with legs. Growth of the primaries is measured to determine age (in weeks) of juvenile birds.

The spurs on the legs of rooster pheasants are the key to telling whether the bird is a juvenile or adult. In this photo, the two legs on the left came from birds that had survived at least one winter. The legs on the right came from young-of-the-year birds. Spur length on an adult male pheasant is generally 3/4 of an inch or more, measured from the outside of the leg bone to the tip of the spur. Adult spurs are also usually shiny black and sharply pointed. Juvenile roosters have spurs that are less than 3/4 of an inch, measured from the outside of the leg bone to the tip of the spur. Juvenile spurs have soft blunt points and dull coloration.

These two roosters were taken on an opening day of pheasant season, within a mile of each other. Both are young-of-the-year birds. The bottom bird is obviously a juvenile. The top bird is fully colored. To tell whether the top bird is an adult or juvenile, you need to check length and appearance of the spurs.

Sharp-tailed Grouse

On their dancing grounds in spring, it’s relatively easy to tell the difference between male and female sharp-tailed grouse. Males are doing the dancing. Females are watching.

In fall, differentiating male sharptails from females isn’t quite as easy, but if you know what to look for, the differences are obvious.

Hunters who send in wing envelopes are also asked to pluck some feathers from the top of a sharptail’s head. There’s a good reason for that.

These sharptail head feathers came from envelopes sent in by hunters. Female feathers (left) exhibit an alternating buff-black striping pattern. Feathers from a male (right) are all black with a buff -colored border.

Male head feathers are black with a buff-colored or tan outside border. Female head feathers exhibit alternating buff and black stripes.

If head feathers don’t do it, look at the central tail feathers. The tips of these tail feathers look similar, so you need to pull them out, or pull back the feathers that cover much of the tail. Central tail feathers of a female sharptail carry buff-black markings similar to those of their head feathers. Male tail feathers have more white in them, and the striping or markings aren’t as consistent.

When you examine an entire grouse tail, you can also judge the bird’s sex. On a male, the feathers running either direction from the center are white and/or light gray. On a female, those same feathers are often mottled with buff/brown markings.

The accompanying photos shows these characteristics. If you know what to look for, it is sometimes possible to judge the sex of a sharptail as it flushes, by whether the tail is brown or white.

Central tail feathers from male and female sharptails. The coloration of these feathers is an indicator of sex. The four feathers on the left came from females. Note the alternating buff-black horizontal striping. The four male tail feathers on the right show more white, and the striping pattern is more vertical and not as consistent as on female feathers.

Pulling away feathers that cover a grouse's tail reveals another way to tell males from females. The feathers on either side of center on the female (left) are mottled. The same feathers on a male (right) are white on the ends and silvery-gray closer to the body.

Aging sharptails is similar to aging other grouse species. If the number nine and 10 primaries are still growing – look for the bluish quill, you’re likely to see this early in the season – the bird is an adult. If primaries seven and/or eight are growing, the bird is likely a juvenile.

If the quills of all primaries are hard and white, that means they’ve stopped growing. If that’s the case, the appearance of the outer two primaries reveals age. If those feathers are pointed and frayed, the bird is young-of-the-year. If those feathers are rounded and smooth, the bird is an adult.

These close-ups of the outer primaries of two sharptails attest to the occasional difficulty of determining whether a bird is an adult or juvenile. The outer two primaries appear similar. Both outer primaries on the wing in the center photos above have smooth tips, indicating an adult bird. But look closely at the number nine (second from right) primary in both photos.

Gray (Hungarian) Partridge

Gray partridge are the smallest of our resident upland game birds. While not a native, they have adapted to North Dakota’s climate and habitat to populate every county in the state.

During hunting season, partridge are usually found in coveys. Coveys often flush en masse, presenting a hunter with a variety of targets. Concentrating on one bird, rather than giving in to the temptation of a flock shot, will lead to more partridge in the bag. Once you have a bird in hand, you can tell whether the bird is a male or female by looking at the shoulder area of the wing.

Males generally have more rust colored wings than females. Female wings are more brown, and exhibit dark brown cross bars and brown mottling on the shoulder patch. Photos in this section show partridge wings with the distinct markings revealing identification of sex.

You can tell whether a partridge is young-of-the-year or adult by checking the molt and/or appearance of the outer primary wing feathers. Early in the season, if the number nine or 10 primaries are still growing, the bird is an adult. If primaries eight or seven are growing, then the bird is a juvenile.

Later in the season, when most birds have fully grown wing feathers, you have to look at the wear on the number nine and 10 primaries. As with many other upland game species, if the outer primaries are rounded and smooth, the bird is an adult. If the primaries are more pointed and the ends are frayed, the bird is a juvenile.

The feather pattern on the shoulder of a gray partridge wing will tell you whether the bird is a male or female. A mottled coloration, overall, and brown crossbars on individual feathers, indicate this wing came from a female.

Shoulder feathers on a male gray partridge are somewhat rust-colored. Dark rust crossbars mark some of the feathers, and males do not have dark brown stripes or mottling found on females.

This wing is from an adult gray partridge. Note the relatively smooth tips of the outer two primary wing feathers.

This wing is from a young-of-the-year male gray partridge. Note the frayed edges of the outer two (ninth and 10th) primary wing feathers.

Ruffed Grouse

It is the opinion of many hunters that ruffed grouse provide the finest table fare of any upland game bird. Yet, they are not widely hunted in North Dakota because their range is isolated to the Pembina Hills, Turtle Mountains and the sandhills in McHenry County.

Ruffed grouse sport different color phases, specifically the color of the band on the tail feathers. The color of the band, whether it’s red or gray, is not a reliable indicator of age or sex.

The central two feathers in a ruffed grouse tail, however, do reveal sex, but you have to pull them out to get started.

If you pull the central tail feathers from two ruffed grouse, and one is about an inch longer than the other, you know you have a male and a female, because males have longer tail feathers. If you have only one ruffed grouse, or you have two and the tail feathers are the same length, you need to measure the feather to determine sex.

Generally, the central tail feather of a male ruffed grouse is six inches or longer. Central tail feathers from a female are shorter than six inches.

The appearance of the band on the central tail feather can also indicate sex, but this method is not always reliable. A distinct black band indicates a male, but males do not always have a complete band. The band on a female is generally not complete.

Ruffed grouse are the most difficult species to age. The best way to tell juveniles from adults is to look at the outer wing primaries. If the outer primaries are growing, indicated by the bluish “quill,” the bird is an adult. If the seventh or eighth primaries are growing, the bird is a juvenile.

In addition, if the outer two primaries are rounded and smooth, the bird is an adult. If those feathers are more pointed and frayed, the bird is a juvenile.

Ruffed grouse live in a more protected environment than other upland game birds. They don’t fly as much, and when they do fly, they don’t fly as far. Since ruffed grouse don’t use their wings as much as other upland game birds, their wing tips may not show much wear, making it more difficult to differentiate young and adult birds whose primary wing feathers are no longer growing.

The best way to determine the sex of a ruffed grouse is to pull out a central tail feather and measure it.

If the central tail feather measures six inches or longer, the bird is a male. If the feather is noticeably less than six inches, the bird is a female. In the photo above, the top feather measures about seven inches, and is from a male. The bottom feathers measure about 5-3/4 inches, and is from a female.

This photo of two ruffed grouse wings is a good example for determining age. The wing on the left is from a juvenile, characterized by frayed ends on the outer primary feather. The wing on the right is from an adult, distinguished by smooth round edges on the outer primary feathers.

Wild Turkeys

Male turkey. Breast feathers are all black. Bright red wattles become evident through spring breeding season, but generally fade away by fall and winter.

North Dakota turkey hunters have the potential to participate in two different seasons, depending on luck in the license lottery drawings. The spring hunt is for males only, while during the fall season both male and female turkeys are legal game.

In the spring, it is relatively easy to distinguish males from females. Gobblers exhibit bright red wattles (engorged skin below the chin) and light blue cheek patches. When a gobbler reacts to an imitation hen turkey call , fanning its tail and breaking into a stupefied dance, there should be no doubt as to the identity of the bird you see over your shotgun sights.

The breeding colors and actions of spring are not so obvious as fall arrives, but if you take your time (if there is time) to study your quarry, you can still usually tell the males from the females.

Fall turkeys are often found in flocks. The biggest birds in a flock are generally adult males. However, if you run across a hen with her brood, size might not be the best indicator of sex. In addition, if you encounter a single bird, you have no basis for size comparison.

Still, sex identification of turkeys is relatively simple if the bird is close enough and you have a second or two to examine it.

Breast feathers on male turkeys, both juveniles and adults, are all black year-round, with one exception. In the fall, if a juvenile male turkey hasn’t gone through post-juvenile molt, its breast feathers may resemble those of a female (black with a buff/tan outer edge).

If the turkey you see looks all black, it’s a male.

The frayed ends on the wing at left indicate a juvenile bird, while the smooth, rounded edges of the wingtips at right indicate an adult bird.

Individual breast feathers from male and female turkeys. The two hen feathers on the left are more dusty colored and exhibit an obvious buff or tan colored band on the outer edge. The male feathers on the right are all black and show a glossy sheen from light bouncing off them.

Breast feathers on female turkeys have a tan or light brown band on the outside edge, and the rest of the feather is not as dark as that of a male. Combined with the rest of the breast feathers, a female turkey appears lighter in color than a male.

In good light conditions, the color difference between males and females is readily visible. If you look at enough turkeys, you can probably tell the difference at any time during legal shooting hours.

Adult male turkeys generally exhibit a long “beard” growing out of the center of their chest. The beard of a juvenile male is extremely short its first fall and often only visible upon cleaning. The beard will stick out slightly by its first spring.

Female turkeys generally don’t have beards, but some do, though they are typically short and hardly visible.

Like other upland bird species, the outer two wing feathers of juveniles will be somewhat pointed and frayed around the edges. Adult primaries are more rounded and have smooth edges.