(A Farm and Ranch Guide to Developing and Maintaining Wildlife Habitat on the Northern Great Plains) - Section 3

Introduction and General Information:

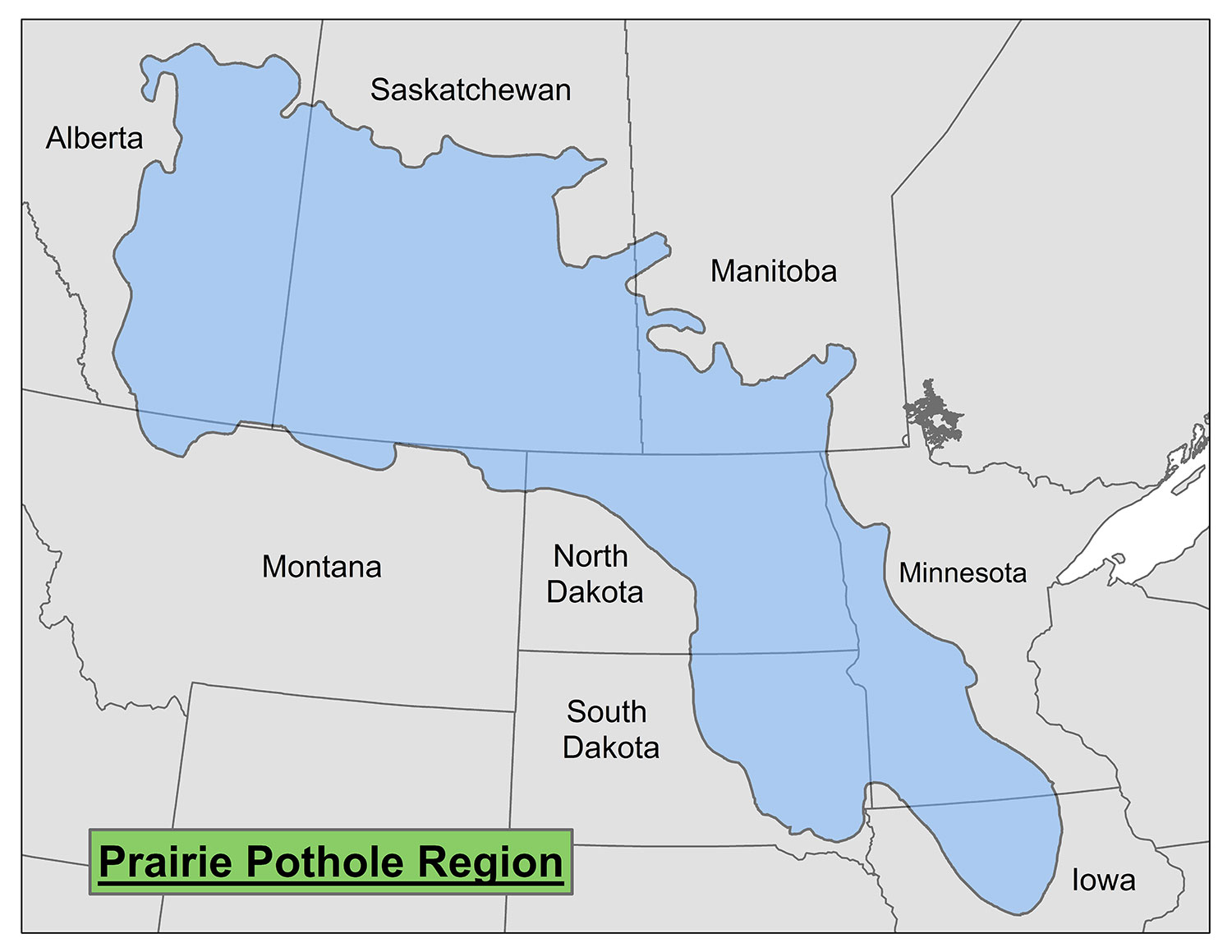

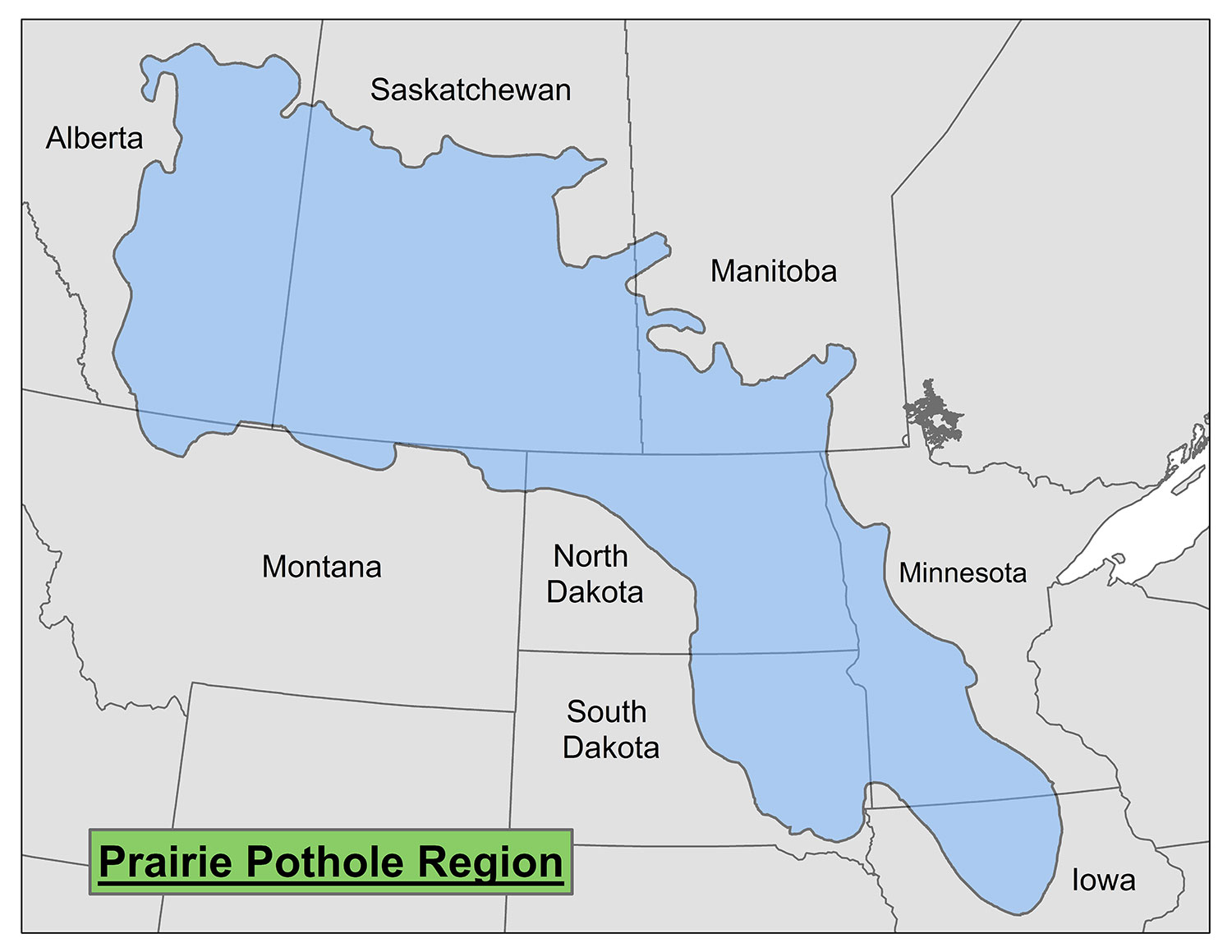

Prairie Pothole Region (blue)

Prairie Pothole Region (blue)Mallards are the most familiar, abundant, and widely distributed dabbling duck in North America. They are also the most prized and sought-after species pursued by duck hunters and have fairly simple habitat needs. Mallard populations have done well in recent years and their population and habitat conditions are closely monitored by managers to ensure their prosperity for the future. The mallard breeds throughout much of the United States and Canada; however, its highest densities can be found in the Prairie Pothole Region of the Northern Great Plains. It is also a common nester in eastern Montana and the western Dakotas when wetland conditions are suitable.

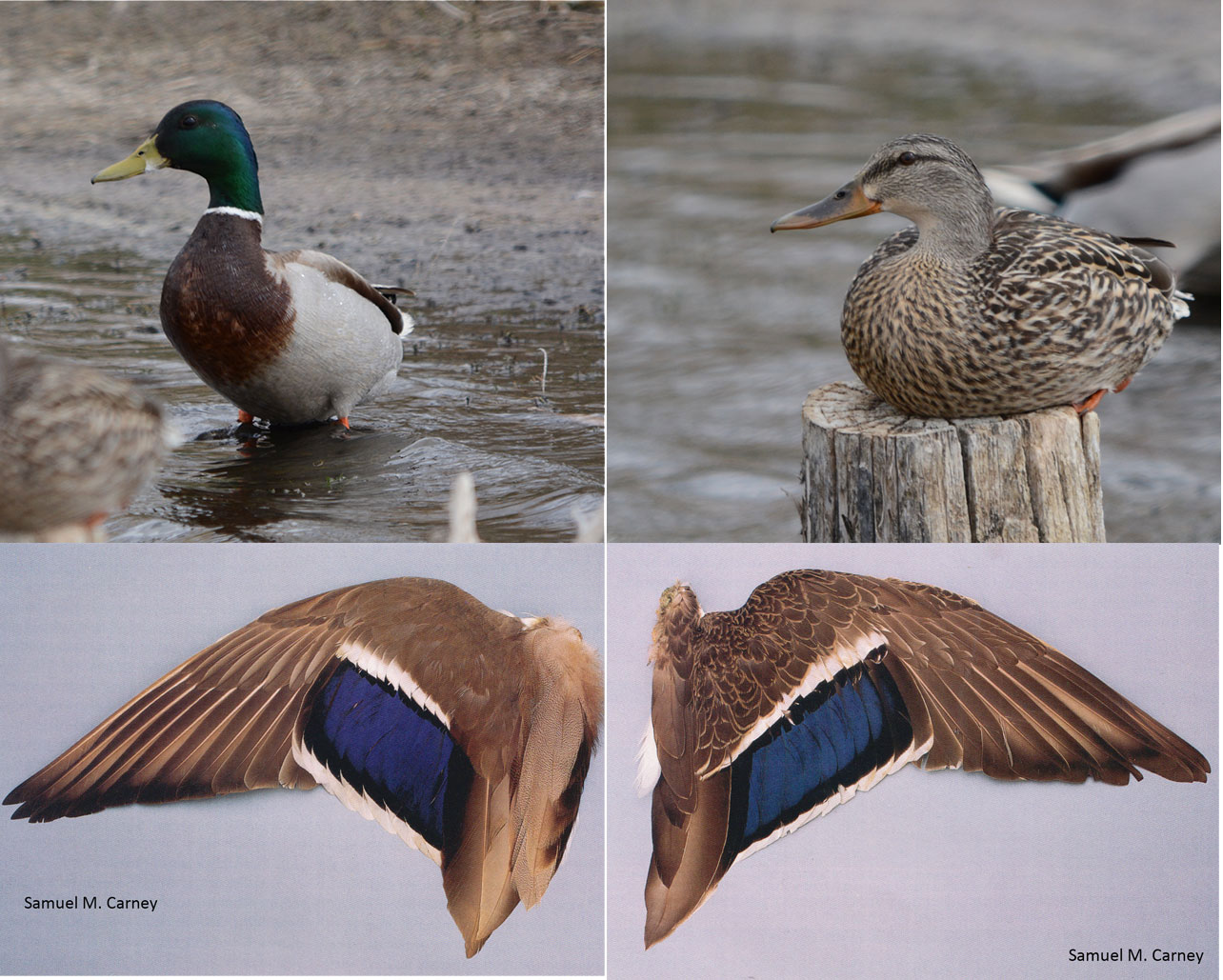

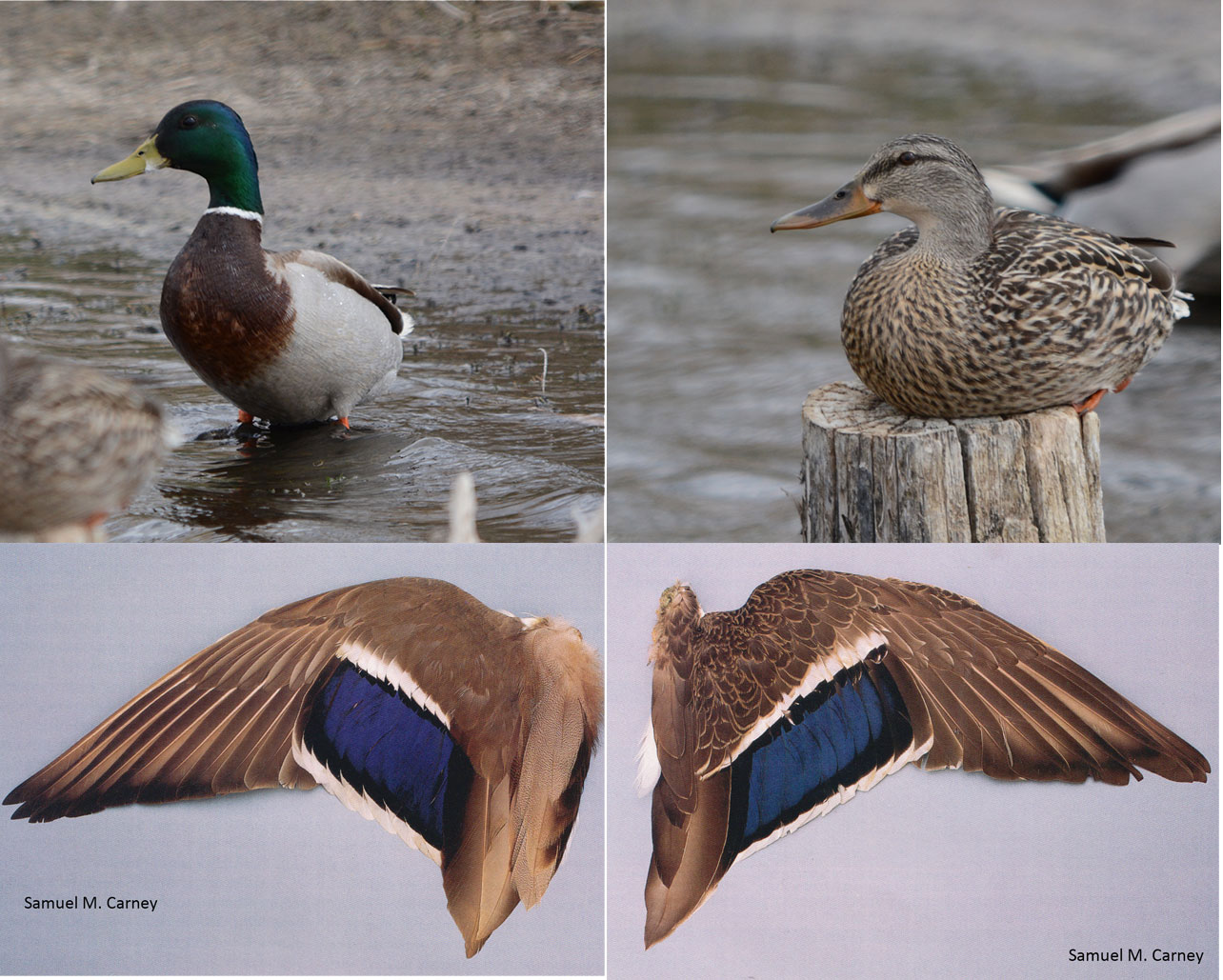

Mallards are large dabbling ducks that weigh about 2-3 pounds; males are more brightly colored and are typically larger than females. Male mallards have breeding plumage characterized by dark green heads, white neck-rings, greenish-yellow bills, brown chests, gray bodies, and black rumps with white tail feathers. Females are characterized by an overall mottled appearance with a pattern of buff, gray, tan and black on brown body feathers, with orange and black splotched bills and whitish gray tail-feathers. Both sexes have gray wings with royal blue secondary feathers that have a prominent white bar on the top and bottom, which extends farther towards the body on females. Both sexes also have orange feet and legs.

Adult male mallard (left), female mallard (right)

Adult male mallard (left), female mallard (right)Most mallards nesting in the Northern Great Plains are medium distance migrants. They usually do not migrate until water freezes or snow covers agricultural food resources. Common wintering areas for mallards that nest in the Dakotas and eastern Montana include suitable wetland and riverine habitat throughout the Great Plains from North Dakota to Texas. However, the largest concentration of wintering mallards occurs in the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain that spans from Missouri and Illinois to northern Louisiana. Mallards are one of the earliest spring migrants back to their prairie nesting grounds, often arriving by late March or early April in the Northern Great Plains for summer.

Mallard diets consist mostly of seeds from natural wetland plants and agricultural crops outside of the breeding season, but nesting hens rely heavily on wetland invertebrates during the breeding season for egg production. Mallards form new pair bonds on wintering grounds each year and maintain the bond until mid-summer. Mallards nest in a wide variety of areas, from undisturbed grass uplands to the fringe of wetlands, but most always select dense vegetation. After selecting the nest site, the first egg is commonly laid within 1 to 4 days; average clutch size is usually between 10-12 eggs. Mallards commonly re-nest if the first clutch is destroyed or abandoned, but clutch size decreases with each effort. Young are typically tended by females alone and walk to water soon after hatching; they are downy and able to feed themselves immediately, but sometimes need to be brooded by the hen to keep warm.

The mallard is renowned for being resilient and highly adaptive to changing habitat conditions, but some key components need to be available for this species to remain successful, especially while on breeding areas in the Northern Great Plains. Another aspect for landowners to consider is that mallards often occupy a large home range and rely on multiple resources to meet their needs during the summer breeding season. Many landowners may not be able to provide all these components, but often these other resources can be found on adjacent properties, so providing even one piece of the puzzle can be beneficial to increasing mallard production.

Breeding Season Habitat Requirements:

Wetland

WetlandFemale mallards exhibit strong natal and breeding philopatry (homing), and hens that nest successfully are more likely to return to the same breeding site. Mallards arrive on breeding grounds as soon as open water occurs and begin searching for nest sites within 5-10 days after establishing home range. Average home range of breeding mallards in the Prairie Pothole Region can vary widely, but studies suggest it averages between 275 and 2,250 acres depending on the amount of resources in the area. The size of home ranges tends to grow smaller with increasing available resources but increase as wetland densities decline. Typical home ranges include the nest site, various feeding areas, and locations where males wait for females to join them during incubation recesses.

Hen mallards rely heavily on a variety of invertebrates to meet the protein and mineral requirements needed for egg production and nesting. These energy requirements are usually gathered using a variety of temporary, seasonal and semi-permanent wetlands (i.e., wetland complexes) during the breeding season. They also prefer wetland areas with diverse shorelines to allow for separation from other mating pairs. Temporary and seasonal wetlands (i.e., small, shallow wetlands that are generally 6 inches to 2-feet deep) are extremely important in providing pair territories and food resources early in spring. Nests are usually constructed in upland areas near water but can be found up to 2 miles away from any wetlands. They will also occasionally nest in wetlands or over water, more frequently than other dabbling ducks. Mallards use a variety of grasses, forbs and shrubs for nesting sites; usually this cover is fairly dense.

Females rearing broods will select areas exhibiting two major components. First, mallard ducklings need wetlands with abundant invertebrate populations for initial development. Second, ducklings need wetland fringes with dense vegetative cover for warmth and protection from predators. Another attractive feature during the brood rearing period are loafing areas, where ducklings can leave the water to preen and dry their plumage. Mallard broods frequently switch wetlands and can move greater than 12 times before fledging, which takes about 7-8 weeks. Slightly deeper wetlands (2- to 6-feet deep, large seasonal and small semi-permanent wetlands) are most productive for brood rearing. Home ranges of mallard ducklings in North Dakota can vary from 10 to 50 acres. After about 20 days, wetland seeds become more frequent in the diets of mallard ducklings.

Management Considerations for Breeding Season:

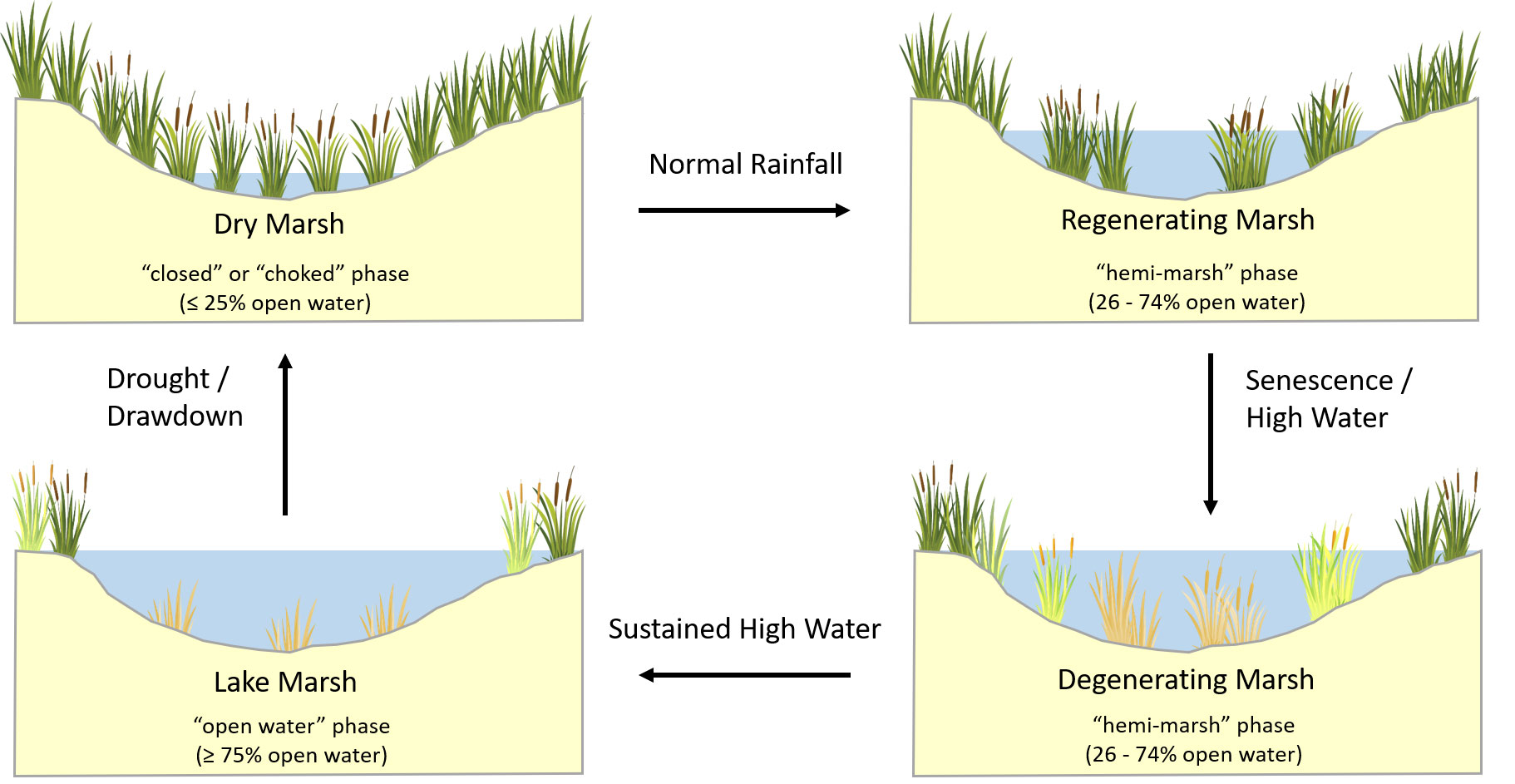

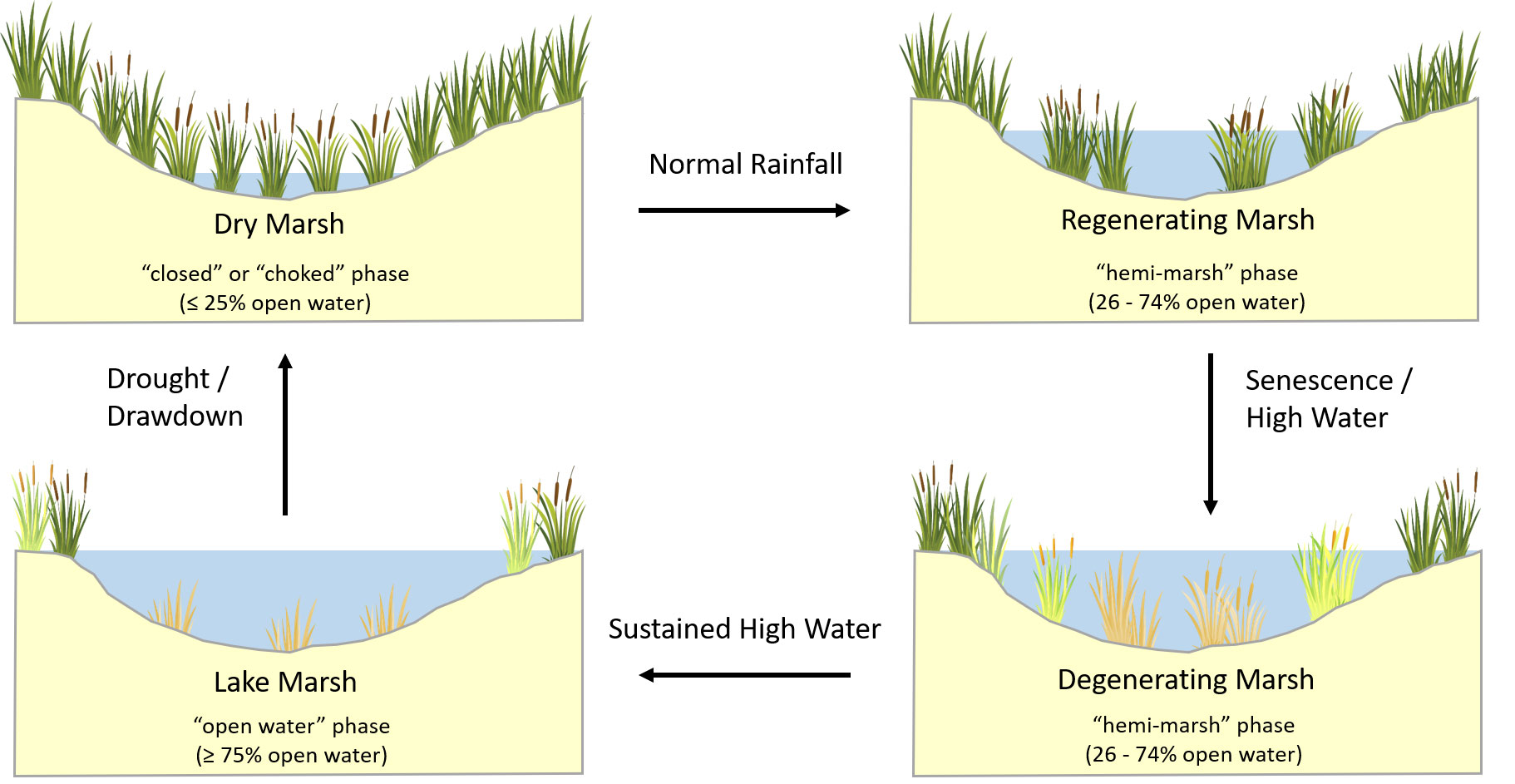

The cover cycle of wetlands is driven by drought and wet periods. Extended dry periods create dry marsh conditions, while too much water floods out vegetation, leading to lake marsh conditions. Fluctuations of normal rainfall allow for hemi-marsh conditions, a category that includes both regenerating and degenerating marsh stages.

The cover cycle of wetlands is driven by drought and wet periods. Extended dry periods create dry marsh conditions, while too much water floods out vegetation, leading to lake marsh conditions. Fluctuations of normal rainfall allow for hemi-marsh conditions, a category that includes both regenerating and degenerating marsh stages.

- Large intact blocks of grassland with high wetland densities are best for attracting breeding pairs and increasing nest success for mallards. Generally, greater nest densities and hatching success will occur within intact grasslands that are 40 acres or greater in size. Seed native or introduced species to plant new areas of ground cover. Native species may take longer to establish, but usually require less management over time. Introduced species can provide good nesting habitat for mallards; a common introduced mixture for dense nesting cover consists of tall wheatgrass, intermediate wheatgrass and alfalfa. Maintaining a cover height of at least 20 inches is most desirable for mallard nesting cover. However, mallards are highly adaptable and will use a variety of cover types for nesting. If large blocks of grassland are not feasible in your farming or ranching operation leave as much dense nesting cover as possible around wetlands, fence rows, odd-areas, roadways, etc.

- Whether native or introduced, grasslands require management to maintain desirable species that are in good condition. Use grazing, prescribe burning and haying on a rotational basis to provide disturbance to these areas and rejuvenate these habitats.

- On islands, planting shrubby species like Western snowberry (Symphoricarpos spp.) or Wood’s rose (Rosa woodsia) for nesting cover will attract nesting mallards. Planting these species will also deter geese and gulls from nesting on the island.

- Use mowing or haying to manage introduced grass stands, but this should be delayed until after August 1 to avoid the primary nesting season of mallards and other upland nesting birds. Use flushing bars to avoid injuring or killing nesting hens during all haying operations.

- Include direct seeded winter cereal crops into crop rotations to provide early spring growth for nesting habitat.

- Manage overgrown wetland cover by mowing, tilling, or burning vegetation to create diverse wetland habitat. Ideal wetlands have a 50:50 mix of open water and emergent vegetation known as hemi-marsh. Herbivores and approved herbicides can also be used to control wetland vegetation and create more desirable wetland habitat.

- Most landowners will not have the ability to manipulate water levels within wetlands on the Northern Great Plains, but drought is a necessary process of prairie wetlands for maintaining productivity of plant seeds and invertebrate communities. As wetlands are inundated for longer periods of time, they will become devoid of vegetation and lose their productivity. Knowledge of the current state of your wetland system(s) may help you better manage your property.

- Although usually expensive, earthen islands can be created and managed to help reproduce mallards by increasing nest success. Construction of small rock islands covered by topsoil is another less expensive option to create islands. Permits to put these materials into wetlands may be required.

- Trapping and removing common nest predators such as skunks, raccoons, and foxes can be used to increase nesting success and hen survival during the breeding period. Consult your state trapping regulations. Excluding predators with electric fences from nesting sites is another method that could be used in certain situations.

- A number of nesting structures such as culverts, hen houses and nest baskets have also been proven to successfully increase nesting success and mallard production. These structures must be maintained and monitored annually. They are most effective in areas with little perennial grassland cover, but abundant wetlands.

- Control tall woody vegetation, including single trees that act as raptor perches and raptor nest sites.

For more information about enhancing and providing and providing nesting cover, see sections on Field Borders and Buffer Strips, Inside-out Haying, Livestock Management, Planting Native Grasses and Forbs, Mechanical Manipulation, and Water Management Control Structures see Habitat Management Practices for the Northern Great Plains.

Fall Migration and Wintering Habitat:

Migrating mallard flock resting and feeding in a wetland

Migrating mallard flock resting and feeding in a wetlandMallards are late autumn migrants and often undergo mass migrations immediately before or during severe snowstorms. They are also known to ride the ice line south during migration, staying as far north as possible until open water is no longer available or deep snow covers agricultural food resources. Typically, most mallards have moved south out of the Dakotas by late November, but small numbers will winter as far north as southern Canada where there is open water.

Nutritional requirements of mallards during fall migration and winter largely involve the energy demands associated with migration and winter survival. To meet these demands, mallards must increase their fat reserves and switch to a diet rich in carbohydrates during this time period. To obtain these carbohydrates, mallards forage extensively in a variety of wetlands for plant seeds, and most use agricultural food sources extensively as well.

Along with food resources rich in carbohydrates, mallards also need good roosting habitat during fall and winter on the Northern Great Plains. Good roosting habitat should contain open water, loafing areas to dry off and preen feathers, and thick emergent cover such as bulrush (Scirpus spp.) and cattail (Typha spp.) for protection from inclement weather.

Management Considerations for Fall Migration and Winter:

- Maintaining wetlands by mowing, tilling, or burning vegetation to produce hemi-marsh conditions and to increase seed production will be beneficial to migrating mallards.

- Abundant wetlands are important to provide natural wetland-based foods, and also decrease flight distances to agricultural fields where foraging may occur.

- Plant small grains such as barley and wheat that are harvested prior to fall migration and can be used by mallards and other waterfowl. Dry legumes such as peas and lentils are also routinely consumed by migrating mallards and are beneficial for building fat reserves. Soybeans are a poor waterfowl food and are not suited to meet the nutritional needs of mallards or other waterfowl. In some cases, eating raw soybeans can kill ducks due to impaction. Corn is a great food that is high in carbohydrates, but it needs to be available during migration. For example, much of the corn planted in North Dakota is not harvested in time to be used by migrating mallards.

- Practicing no-till farming or delaying plowing until spring on agricultural fields will leave more waste grain available for mallards. After plowing of agricultural fields greater than 90% of the available waste grain can be buried and become unavailable to waterfowl.

- Field feeding waterfowl can remove weed seeds and enrich the soil with their droppings. Foraging by waterfowl can also reduce the amount of unwanted sprouting from residual waste grain.

If you are interested in restoring a wetland, or developing an impoundment that would benefit waterfowl, contact USFWS Partners for Fish and Wildlife program. They might be able to assist you with engineering, construction and cost-sharing for the project. Also, you might consider contacting Ducks Unlimited for assistance (Appendix A).