Habitat Needs of White-Tailed Deer

(A Farm and Ranch Guide to Developing and Maintaining Wildlife Habitat on the Northern Great Plains) - Section 2

White-tailed deer are an adaptable species and do well across much of North America; however, deer management can be complex and can vary from place to place.

Habitat requirements of newborn fawns differ from those of adult deer, resulting in management for a variety of habitat types and arrangements. Fawn survival is an important part of population growth and is often more variable from year-to-year than adult survival due to their susceptibility to predation and environmental extremes. As a result, understanding what factors influence fawn survival is an important part of management.

For more than 20 years we have collected information from radio-collared fawns and adult females that were captured in 20 counties across southwestern Minnesota, South Dakota and North Dakota. The following section discusses what variables affect white-tailed deer survival and habitat use in the Northern Great Plains and how habitat on your property can be improved for this important big game species.

Life History of White-tailed Deer in the Northern Great Plains

The mean birthing date for white-tailed deer in the region is June 6, with more than 70% of the births occurring within two-weeks of that date (May 23 to June 20), and more than 90% of fawns are born between May 9 and July 4. During much of the first month, fawns spend most of their time bedded and hiding from predators. On average, the home range of a fawn during this first month is a little less than 100 acres, or a circular area with a radius of about 400 yards. By three-months of age, the fawn’s home range has grown to about 350 acres, or a circular area with a radius of about 730 yards. By the end of September, fawns are weaned from nursing, are following their mother wherever she goes and are generally able to outrun predators.

Nursing a fawn is the most energetically demanding period for a female deer and requires more than six times the nutritional demands of just maintaining her own physical requirements. As a result, an adult female deer with a fawn needs highly nutritious food sources and readily available access to water. Even after the fawn is weaned, the mother will continue to need highly nutritious foods to put on fat reserves for winter. The summer home range size for female deer in the Northern Great Plains is more variable than that of the fawn, ranging from less than 1 square mile to nearly 4 square miles; however, the average is about 1.5 square miles.

During summer and fall, males move more widely over the landscape and are often seen in small bachelor groups. Antler development starts in May and growth is completed and velvet begins to shed by the first week in September. As the rut progresses, bachelor groups disband and sparing between bucks becomes more frequent. The rut in the Northern Grate Plains peaks between 10 and 15 November. As with the birthing of fawns, more than 70% of the breeding occurs within two-weeks (October 23 and November 20), and nearly all breeding ends by the first week in December. With decreasing testosterone levels and the declining body condition of bucks, antlers start to shed in late January; however, if the winter is mild, and the buck is in good condition, antlered bucks have been observed into early April. Generally, antlers are cast within six days of each other.

Many deer die each year from grain overloading.

Winters on the Northern Great Plains can range from relatively mild to extremely severe. The primary drivers influencing white-tailed deer survival, in addition to harvest, are cold temperatures, snow depth and the length of time these factors persist.

On the Northern Great Plains, extreme conditions of continuous snow cover and cold temperatures can extend from early November into April. Deer in good physical condition can withstand these cold and snowy conditions well into February. However, if cold and snow persist into March and April, winter mortality can be high.

The loss of deer during winter often follows a progression, with spent bucks, injured deer and small fawns being found dead in January. If severe conditions persist into February, fawns-of-the-year begin to die at increasing rates. When cold and snow cover last into late March and early April, mature adult females die at increasing rates.

This said, during most winters, deer that are found dead often do not starve to death but die from grain overloading. Grain overloading occurs when deer get access to high carbohydrate foods, such as shelled corn and grain screenings. These foods cause increased acidity in the rumen of a deer’s stomach, resulting in a condition called acidosis. It takes less than one quart of corn to kill a fawn. Although shelled corn can cause acidosis, deer feeding in standing and/or harvested cornfields are generally not susceptible to acidosis as corn stalks and other roughage material ingested helps to maintain the pH levels within a deer’s rumen. In recent winters, between 30 to 40% of the deer brought into the North Dakota Game and Fish Department wildlife health lab died from grain overloading and acidosis.

The keys to maintain deer during winter are to:

- reduce and avoid disturbances of deer in wintering areas that increases their energy demands,

- provide access to browse, food plots or cover crops, and

- provide nearby resting cover that does not require deer to cross highways to reach food sources.

For more information on providing thermal cover and winter food sources, see the above section on Habitat Management Practices for the Northern Great Plains.

Fawn Rearing Habitat Availability

Newborn white-tailed deer fawns require habitat that allows for concealment from predators and will help them to maintain their body temperature. However, newborn fawns are restricted to the habitat found within about a 100-acre portion of their mother’s home range. Knowing what habitat is present within a fawn’s home range compared to its mother’s home range allows targeted management to ensure enough habitat is available to attract and provide food for adult females and security for their fawns.

We conducted an analysis that allowed the ranking of habitat types by those most prevalent within fawn home ranges. We assessed percent of open water, development land (farmsteads and roads), wooded or forested areas, shrub, grassland, cropland, wetland and pasture habitat types.

We found shrubs and grassland areas were the two most prevalent habitat types within home ranges, followed by developed areas. The amount of shrubby area, grasslands and developed areas found within a fawn’s home range was 45%, 31% and about 7%, respectively. The amount of cropland found in a fawn’s home range was less than most other habitat types, indicating that there is less of this habitat used by fawns. This is likely related to the lack of hiding cover agricultural crops provide within the first two weeks of a fawn’s life, a time when fawns are immobile and rely on hiding to avoid predation. In contrast, the amount of shrubby area, grasslands, farmsteads (both abandoned and occupied) and road ditches were greater than most other habitat types.

Although shrubby areas and grasslands are considered high quality fawning areas, we do not usually associate developed habitat types as important fawning habitat. Farmsteads are generally comprised of combinations of tree rows, low shrubs and open areas that increase habitat complexity. This combination of vegetative structure often provides fawns with the cover needed to avoid predators and can be rare in agriculturally dominated landscapes (Figure 1). During late summer, once row crops average 33 inches in height, fawns begin to use these fields as hiding and escape cover from predators.

Although fawns were found in areas with less cropland, cropland still comprised a large proportion of fawn (about 30%) and maternal (40%) home ranges. If your property contains more than 40% of agricultural fields, then fawning cover is likely limiting. If so, property can be enhanced for deer by managing for multiple habitat types such as grasslands, wetlands, pastures and forested areas that are within an area of about 350 acres (730-yard radius) from one another. Doing so will create cover patterns that will maximize a fawn’s ability to conceal themselves from predators and reduce movement between isolated cover habitats, which can predispose fawns to predation.

For additional information on how to enhance fawn rearing habitat, see the sections on Field Border and Buffer Strips, Planting Native Grasses and Forbs, Planting Shrubs and Trees, and Forest Management .

Bed Site Selection

Although fawns are restricted to habitats available within their mother’s home range, fawns choose their specific bed sites. Fawn bed sites can be found in several different habitat types including grasslands, wetlands, forested areas, alfalfa fields, small grain fields and pastures. Despite the variety of habitats used for bed sites, research has shown that most bed sites are found in grasslands, wetlands and forested areas; again, indicating that these habitat types are important fawning cover.

Vegetative structure found at individual bed sites also is important. Fawns tend to select bed sites with taller, denser vegetation, and areas with an overhead tree canopy. Dense vegetation helps conceal a fawn from predators and can reduce scent, which decreases a predator’s search efficiency. Dense vegetation also helps to regulate the ambient temperature at the bed site, which reduces the chances of fawns dying from hypothermia. Some research in South Dakota has shown that fawns are more likely to die from hypothermia in habitat types such as wheat fields when bedding on bare ground.

Tall understory is only one of the important vegetative structure characteristics that influences where a fawn will select a bed site. Canopy cover also is important because it can protect fawns during rain events and can reduce temperature variability, both of which decrease the chance of a fawn dying due to hypothermia. When managing for fawning cover on your property, incorporate habitat types such as grasslands and wetlands with vegetation that will reach an average height of at least 16 inches. Overhead canopy cover provides the fawn shade and protection from rain and the elements. Periodic openings in the tree canopy allow for an increase of understory cover. Ensuring that grasslands or wetlands are adjacent to wooded areas will maximize the availability of high-quality fawning cover on your property (Figure 1).

Although vegetation continues to grow and change structure throughout the fawning season, newborn fawns tend to use the same types of habitat (e.g., grasslands and wetlands) regardless of when they are born. The primary fawn birthing season lasts from about May 23 to June 20, which means that newborn fawns will be using grasslands and even some agricultural fields such as wheat and alfalfa until early July. Remember, newborn fawns are not mobile and cannot outrun a combine or brush hog so mowing these habitat types may be lethal. Mowing can still be accomplished during summer, but if you wait until after the majority of fawns are old enough to run away, and you mow in a pattern that allows them an escape route, you will improve their chances of survival. A conservative strategy of mowing before May 9 with a second cutting delayed until after July 4 would allow most fawns to become mobile and escape machinery, but an even more conservative strategy would be to wait to mow until July 24. For more information on enhancing management for fawn bedding sites see sections on Edge Feathering, Field Borders and Buffer Strips, Inside-out Haying, Livestock Management, Forest Management, Planting Native Grasses and Forbs, and Planting Trees and Shrubs.

Adult Habitat and Food Availability

Between May and August, most of a deer’s diet is forbs and the growing stems of trees and shrubs. During fall and winter, crops become an increasing component of the diet, and as winter snow cover melts in spring, fresh shoots of grasses and sedges are sought after. Water availability is also important to consider. Water intake needs are influenced not only by the type of food deer consume, but also the time of year. Having water in relatively close proximity for a female white-tailed deer is important during lactation when a female’s energetic demands increase to produce milk. Managing for at least one water source per 350 acres should allow lactating females to meet their energetic demands for milk production. Water sources should be about 2.5 acres in size. However, if wetlands are not present on your property then other water sources such as guzzlers or farm ponds will likely serve as adequate water sources.

Trees for antler rubs are a habitat feature that are important for males on the prairie because they act as visual cues to other deer indicating a buck’s presence in an area. Based upon research done on the South Dakota prairie, trees bucks selected to rub were 1 to 4 inches in diameter at chest height, were aromatic species, had smooth bark, and did not have thorns. Tree species that have these characteristics include chokecherry and juneberry. Bucks avoided using green ash, hawthorn, boxelder and wild plum.

Habitat also influences the home range size of adult female deer. For example, when assessing what habitat characteristics most influence summer home range size of females located in Grant and Dunn counties in North Dakota and Perkins County in South Dakota, we found that that the increased amount of wetlands and forested areas decreased overall home range size for individual deer. For winter home ranges, the increasing amount of forested area still decreased the overall home range size for a deer, whereas home range size increased with an increasing amount of corn. Forested areas can provide much needed cover during both summer and winter and having about 5% of a doe’s home range comprised of forest will provide adequate cover. Although home range size increased with an increasing amount of corn, that does not account for harvested versus standing corn fields. Standing corn fields can provide much needed energy during the most severe winter months and leaving standing corn can be an effective management practice to provide food, provided there is enough food to last through the winter. Knowing what habitat types influence home range size can help you hold deer on your property year-round.

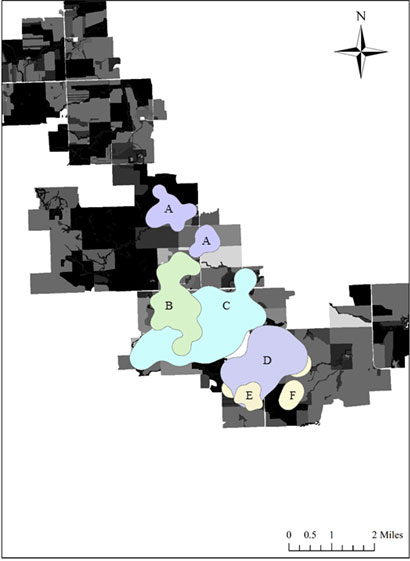

Home range sizes of female deer in the Northern Great Plains tend to be larger than in other parts of the country. For example, the average size of a female’s summer home range averages 1.5 square miles and the average winter home range size can be over 4 square miles. This means that unless you own or manage over 2,500 acres, deer that use your property are also likely using your neighbor’s properties as well. Deer home ranges also tend to overlap (Figure 2). The large size of a deer’s home range emphasizes the importance of working with your neighbors to reach your management goals. For example, ensuring that you can provide whatever is lacking on your neighbor’s property and vice versa will oftentimes help cut down on costs of habitat improvement projects, while still providing deer with food, water and cover. For more information about enhancing and providing year-round food sources for deer, see sections on Field Borders and Buffer Strips, Cover Crops, Promoting Forbs, Planting Food Plots, Leaving Crops Unharvested, Tillage Management, and Water Management Control Structures .

Fawn Survival

Although coyotes are generally considered the top predator of fawns in the Northern Great Plains, coyote predation does not always mean that you have a problem on your property. For example, several studies conducted in the Northern Great Plains have reported high fawn survival in the presence of coyotes. Even in situations where coyotes may be negatively influencing fawn survival, predator management is often difficult and costly. Therefore, managing fawning habitat is often a more feasible way to increase fawn survival in areas where fawn survival may be limiting population growth.

Fawns display two predator avoidance strategies early in their lives. Fawns are mostly immobile and rely on their camouflage to hide from predators during their first month of life (hider strategy). After one month, fawns begin to follow their mother and are better able to escape a predator (fleeing strategy). Fawns in the Northern Great Plains are usually most susceptible to predation within the first two to four weeks of their life, though they can still die due to predation throughout summer. Habitat requirements for fawns therefore differ depending on fawn age and subsequent predator avoidance strategy.

The weather a fawn experience at and immediately after birth can influence its survival. When assessing weather conditions during June (the month when most fawns are born) for fawns that were captured between 2001 to 2015, surviving fawns generally experienced warmer and wetter weather than fawns that died. Surviving fawns experienced environmental conditions during June that were about 1 degree warmer and had about three tenths of an inch more rainfall than fawns that died. Although these differences seem small, they account for an 11% increase in average June temperature and a 7% increase in rainfall during June for surviving fawns. This means that about a 10% difference in temperature and rainfall can influence a fawn’s survival during its first month of life.

Obviously, there is no way to manage weather, but these results emphasize some important aspects of white-tailed deer biology. Warmer and wetter springs are related to an increased flush of spring vegetation, which is important for newborn fawns for two reasons. First, it provides quality fawning cover early in a fawn’s life. Remember, fawns are most susceptible to predation during their first two weeks when they are trying to avoid coyotes by hiding, so having quality hiding cover during that time is important. Second, an increased flush in vegetation means that there is more abundant, highly nutritious food available to the mother earlier in spring. During May and June, females are recovering their body reserves from winter and then immediately transition into birthing fawns with lactation being the most energetically demanding period for females. Having abundant, high-quality food resources available during this time period helps ensure a female fully recovers her body reserves and can successfully raise her fawn(s).

Cover habitat is an important feature on a property and can influence fawn survival once they become mobile. Managers generally quantify cover habitat as the number of distinct patches of habitat on a property with there being two main components: patch type and arrangement (Table 1). Patch type simply indicates what type of habitat is on the landscape, whereas arrangement indicates how those patches are connected to each other. Managing for about two patches of grasslands or wetlands per 350 acres (home range size for a 3-month-old fawn) will positively affect fawn survival. However, remember that the arrangement of those patches also is important. One study conducted in the Northern Great Plains showed that surviving fawns generally had about 80% of cover patches located within 730 yards of each other (Figure 3), whereas fawns that died had less than 70% of cover patches connected within that same distance (Figure 4). Managing for quality habitat cover such as grasslands and wetlands that are within 730 yards of each other allows fawns to escape from predators because chance of survival decreases with the increasing distance when it is flushed and has to run (outrun a coyote) to the next cover patch. At times, coyotes may use large round bales as observation platforms for hunting. By bringing hay bales into a central hay yard, you will not only protect your forage from potential deer depredation, you may also be reducing the hunting efficiency of coyotes.

The amount of wooded area found on a property can have various effects on deer use and survival. For example, the chance of holding adult deer on your property throughout winter increases with the number of forested patches found per 350 acres. As we already discussed, the canopy cover provided by trees potentially helps fawns thermoregulate during inclement weather. However, some research has shown that the amount of forested area found on a property can negatively affect fawn survival. This may seem counterintuitive, but it could be because shelterbelts are generally planted linearly, and at times consist of just a single tree row. These narrow bands of habitat may improve a coyote’s ability to search for bedded fawns, though more research is needed to verify this finding. Regardless, this emphasizes the complexity of managing for white-tailed deer as different cover habitats are more beneficial to deer, based upon the size and shape of the cover and the age of the individual.

Winter Cover and Food

Deer will bed in open fields during winter. Shelterbelts, tree rows and cattail sloughs offer deer hiding cover and protection from the wind during winter. During snowy winters, these areas can fill in with snow and become unusable for deer. We suggest tree plantings intended to provide winter thermal cover should be 8 to 16 row shelterbelts and/or block plantings. Another solution may be to plant rows of conifers on the north and western sides of existing shelterbelts and tree rows, or a “living snow fence” of conifer trees to the north and west of cattail sloughs. To minimize negative impacts on waterfowl using these wetlands, tree plantings should be at least within 300 feet of a wetland as these trees may provide hunting platforms for hawks and owls. If possible, food sources for the winter should be placed near winter cover. Food plots planted for deer should be of adequate size (minimum 2 to 10 acres) to provide food throughout winter. For more information on winter cover and food, see sections on Planting Trees and Shrubs, Cover Crops, Food Plots, Leaving Crops Unharvested, and Tillage Management.

From Deer Research to Deer Management

So how can you improve fawning habitat on your property? First, you need to make sure that you have abundant fawning habitat available, particularly if agricultural crops comprise more than 40% of your property. If agriculture is a dominant land use on your property, then consider enrolling acreage into federal programs such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). If possible, implement these programs in areas within 400 yards of other types of fawning habitat such as wetlands, pastures or forested areas. Doing so will ensure a diversity in vegetative structure and create complex habitat suitable for fawn concealment. Also ensuring that there is at least one water source per 350 acres is important. Including your neighbors when considering habitat improvements may also be important depending on the size of your property. If you own less than 350 acres, then you may not need the same amount of fawning cover if adequate cover is available on the adjacent property. Conversely, you may need more fawning habitat if you own more than 350 acres, so plan accordingly.

Remember that habitat management takes time to implement and needs to be maintained, but in doing so you will create prime fawning cover that will allow for the maximum number of fawns to survive while benefiting other juvenile and adult white-tailed deer on your property. For more information about minimizing your long-term costs for enhancing habitat on your land, see the sections on Conservation Easements, and Appendix A.

| Habitat Type | Percent | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Open Water | 3.6 | 0.0 - 61.7 |

| Developed | 4.3 | 0.0 - 13.4 |

| Forest | 1.7 | 0.0 - 30.3 |

| Grassland | 29.5 | 0.0 - 98.3 |

| Cultivated Crop | 36.6 | 0.0 - 96.7 |

| Wetland | 5.9 | 0.0 - 64.3 |

| Patches Connected | 76.5 | 0.0 - 100 |